When we work on projects, we are often pressured by timelines and stakeholders to move on with our designs as quickly as possible. We need to be able to advocate the value of iterative design, to ensure that we are building the right thing, in the right way.

We’ve all worked on projects with tight deadlines. You’ve completed your research and analysis, but time is tight, and the stakeholders are keen to see progress, often so that they can show it to their superiors. You find yourself pressured into producing designs, where you only have one round of changes before you’re asked to move on to something new, because there isn’t time for more work on that part of the problem. We know it’s wrong, but we move ahead, because we’re worried that challenging our team members will be a losing battle.

As we know, the problem here is that we’re not being given sufficient time to iterate upon our designs. This, in turn, provides other problems: - We are not testing our assumptions: inevitably, during the analysis and design process, while having some knowledge gained from research, we will make assumptions that have not been verified. If these are not tested, we have no way of knowing whether they are correct, and therefore whether this solves user requirements and issues. - We are not getting feedback: as well as seeing if our assumptions are correct, we are not getting clear feedback from the users for the designs themselves. Perhaps the way in which we have designed the solution may offer up new problems that we had not previously considered, and would not be aware of, had we not tested them with users.

One of the major causes of this is due to a misunderstanding of the design process. Stakeholders assume that designs are produced the first time, and don’t understand that designs should be iterated upon. I was reminded of this recently, when listening to the 99% Invisible podcast, where the two hosts, Roman Mars and Kirk Kohlstedt, were discussing the story of the creation of Catseyes.

Catseyes, a story of iterative design

The original story

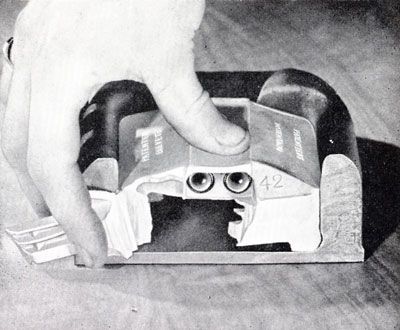

An original form Catseye in the UK (ELIOT200 on Wikipedia, public domain)

An original form Catseye in the UK (ELIOT200 on Wikipedia, public domain)

Catseyes were invented in 1933 by Percy Shaw, an inventor and engineer from Halifax in Yorkshire¹, who had his own asphalting business. One foggy night, he was on his way home from The Old Dolphin, a pub in Queensbury village, to his home in Boothtown. As he was driving on the poorly lit roads, which often had steep drops off to the sides, he often relied on following the tram lines to know which direction the road was turning. That night, however, he found a stretch of road where the tramlines had been taken up, meaning he had nothing to navigate by. It was then that he noticed the light of his headlamps reflected in the eyes of a cat, walking along the side of the road. He was so fascinated by this phenomenon, he slowed his car to a stop, and it was then he realised that not only was he on the wrong side of the road, but also that if he had carried along the same route, he would have veered off the road and plummeted to an almost certain death.

The story continues that he was so inspired by this event, he went and designed the Catseye, a device that sits in the middle of the road, indicating the boundary between each side of the road and the other by reflecting the headlamps of oncoming traffic back at them. This device became popular across the world, saving many drivers from accidents, made a fortune for Percy Shaw, and gained him worldwide recognition, and an OBE from the Queen for his efforts.

Catseyes on the M6 motorway in Ireland (Zoney on Wikipedia, CC BY-SA)

Catseyes on the M6 motorway in Ireland (Zoney on Wikipedia, CC BY-SA)

I remember reading about this in a children’s encyclopaedia when I was young, and it being one of the the early moments where I was fascinated with design. I learned about their construction, how they consist of two glass beads which emulate the eyes of the original cat that inspired Shaw by reflecting the light back towards the source, mounted in a rubber foot so that cars could pass over them without crushing the housing and the beads, which in turn is housed in a cast iron casing, allowing the device to be embedded in the road with asphalt and held in place. The best thing was, I could actually go out onto the road outside my parents house (with a careful eye out for oncoming traffic) and see them in action, pushing them down to see how they worked when a car drove over them. It was here that I learned that they also incorporated extra design elements, including a small reservoir which collected rainwater, and rubber flaps which would wipe the surface of the glass beads as the Catseye was pressed down.

Cutaway of a Catseye, showing the flexible housing, the reflective beads, and the rubber wipers.

The development is in the details

Details such as these are often missed, as we are often told the story of the success, and not the considerable periods of trial and error that go towards achieving that success. It is assumed that inventors, designers, and engineers push out fully realised and perfected designs on their first go. Little appreciation goes to the fact that these endeavours take iterative design and testing in order to ensure success.

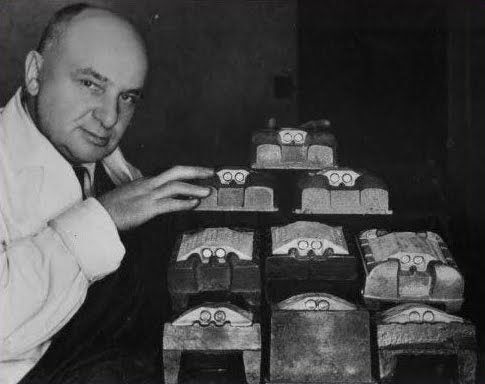

Percy Shaw, with his various prototypes of the Catseye

With Percy Shaw, his ideas took time to develop. He built various prototypes of his Catseye invention, in order to explore ideas and see if they worked. He would then go out at night and dig up nearby roads, without permission from the authorities, driving his car up and down them to see if his prototypes were functioning properly. He would then be able to repair the roads himself, using the knowledge and skills he gained from the asphalting company he owned. This somewhat unconventional method paid off, as he was invited in 1937 to demonstrate his invention in a competition to the Department for Transport, who were concerned about the growing number of night-time traffic accidents in the country, by placing 50 Catseyes on a busy stretch of road. His invention won the competition, as the other participating inventions either broke or were deemed ineffective.

It was only during the Second World War that Shaw’s invention became popular, when the Government banned the use of street lighting, so as not to provide reference points for enemy bombers. As the Catseyes only reflected back the light in front of them, and not upward, road users could find their way safely, without shining light upwards. What’s more, they required no external power, were self-cleaning, meaning that they could be installed on stretches of road in remote areas without requiring wiring or maintenance. This popularity meant that Shaw’s company, Reflecting Roadstuds Ltd, grew to 130 employees, and ended up manufacturing over a million Catseyes a year, for shipping around the world. His invention is credited with saving the lives of thousands of motorists around the world².

Shaw’s success with Catseyes was down to being able to try different ideas, test and evaluate them, and make adjustments based upon what he found. By taking this approach, he was able to anticipate possible problems, such as what happens when a car drives over them, or many cars over a period of years, or if they get dirty, and so on. Without doing this, his invention would probably have suffered the same way his competitors did in front of the Department for Transport, and would not have gone on to enjoy the success it did afterwards.

Ensuring iterative design in your project

Starting the right way

Whilst Shaw had the benefit of being head of his project, and therefore being able to allocate the time he needed. How can we ensure that we get the chance to test and develop our ideas in projects? The trick is to bring the expectations of your team in line with your own; and to do that, you’ll need to start early. At the beginning of the project, sit down with your team and take them through the following:

- Fully explore the brief: instead of just accepting the brief as it is given, take time to explore and understand the problem, how the team expect to approach it, and what they expect from you, and what you expect from them.

- Present your process: despite the fact that your team might have worked for years in production, they still may have differing understandings of what processes are used, so take them through the process you intend to use on the project, from start to end. This helps to align their expectations with yours, for you to explain why you have chosen this approach, and for them to fill in any gaps in their knowledge and understanding by asking questions.

- Add your process to the overall plan: inevitably, if your project has been set to a limited time frame, those managing the project will have set out a rough plan to define a guide to measure progress throughout the allotted time. In order to ensure that you get the time that you need to conduct each part of your process, you will need to work with them to map out the process on their plan. By agreeing this with them beforehand, you have a record of the intended plan, which can help you protect the time that you require.

These methods may seem obvious and simplistic, but I have witnessed projects become severely limited by people not observing them. By taking these steps, you can ensure that everyone understands the approach, you have the time to iterate, and you don’t run into problems later.

Proving that iterative design works

Should anyone on your team question the value of iterative testing and design—and may not have the time for you to regale them with a tale of the invention of self-sufficient road studs in Yorkshire in the early part of the 20th century—then you may find it useful to show them a diagram that Josh Sieden (one of the co-writers on Lean UX) used in a talk on iterative development recently:

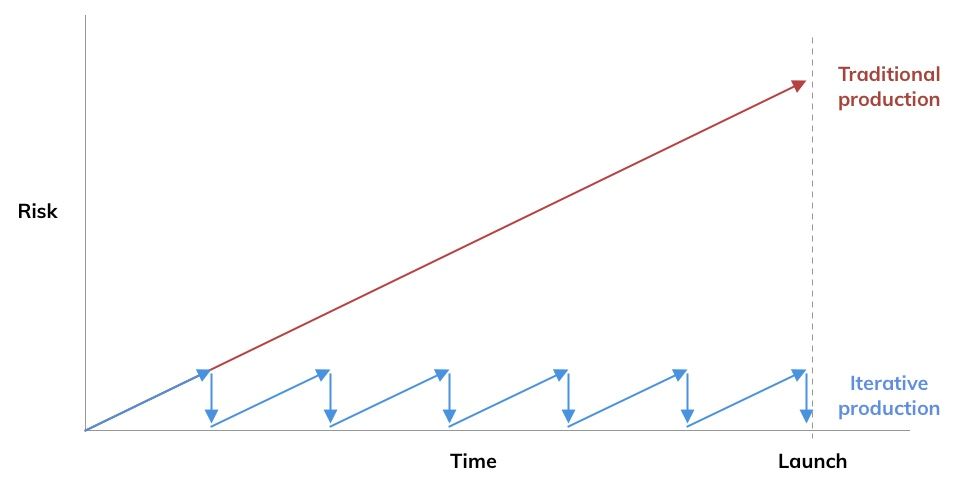

Traditional vs Iterative production (from a talk by Josh Sieden)

Traditional vs Iterative production (from a talk by Josh Sieden)

This graph shows the difference between production in an traditional way, and an iterative one. With time on the horizontal axis, and risk on the vertical, a traditionally produced product (the line in red) will be continually developed without testing, increasing in risk until it is launched, when it is then discovered whether it solves the issues that users face. In the case of a product that is produced using an iterative process (the line in blue), each part is devised, and then tested, thereby reducing the risk to almost zero each time, as sufficient testing will nullify that risk by challenging any assumptions made, and ensure that users are happy with the product, before moving on to the next part. This should show your team just how, by following an iterative approach, they can launch a product with the assurances from testing that it will be successful, instead of merely hoping that it will be.

Conclusion

The iterative design approach is vital to ensuring that your product is successful, resilient, and addresses the problem, and, as the example above with Catseyes shows, can be used in a variety of scenarios. Hopefully the above should inspire you to approach new projects with the confidence and tools to advocate for iterative design, and I hope that, by doing so, you can continue to help advocate its worth to everyone who is involved in production.

Notes:

- Shaw filed a patent for the Catseye in 1934, but it is also worth noting that his invention made use of reflective lens by Richard Hollins Murray, and that a similar patent was taken out by Freddie Lee two years earlier for reflectors mounted in the road, who had to abandon his application due to patent registration and maintenance costs.

- Sadly, not everyone has been so fortunate, Kemi Olusanya (a.k.a. DJ Kemistry) was killed by a loose Catseye while travelling back from Southampton to London in 1999. Forensic scientists found afterward that this was down to a lack of bitumen in the surrounding asphalt, and poor installation.

Sources:

“Decoding Cat’s Eyes: A Global Color Guide to Reflective Road Markers”, 99pi.org “Percy Shaw”, Wikipedia “Percy Shaw O.B.E — 15th April 1890 to 1st September 1972”, Reflecting Roadstuds Ltd “Design Museum — Sept 13 2014” web.archive.org