Timezones, and daylight saving - the practice of moving clocks forward by one hour once a year - are a pain. They make it hard to schedule international meetings, plan travel, or may simply cause you to be an hour late for work once a year. For a developer, they are even worse!

The number of things that can trip you up about date and time handling is astonishing. For a quick taster, I’d recommend reading the list of things you believe about time that are likely false. It’s no wonder that even the latest gadgets, such as Google Pixel and Apple Watch still exhibit significant bugs relating to how they handle the passage of time.

Recently I’ve been working on a few libraries for AssemblyScript, a new TypeScript-like language that targets WebAssembly. The library I am currently working on is assemblyscript-temporal, an implementation of TC39 Temporal, the new and vastly improved time API for JavaScript. In implementing the timezone-aware components of that API, I’ve delved deep into the IANA database, the standard reference for timezones, which contains thousands of rules encoded in text files.

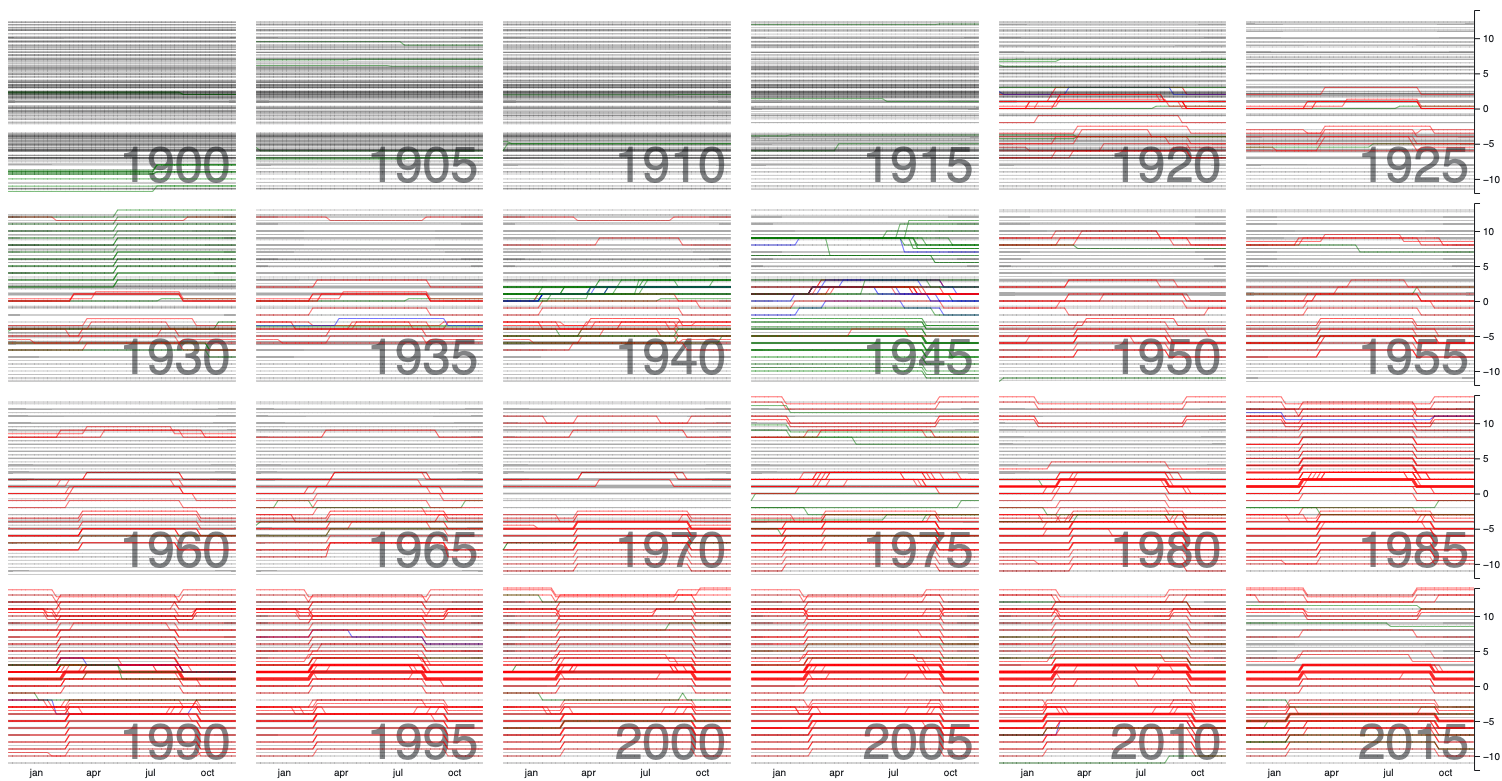

While scanning these files I came to realise that timezones were even more complicated than I had originally understood, with the rules in a constant state of flux. I was intrigued to see what patterns might emerge if I could visualise this dataset in its entirety, which led me to come up with this:

view as a fullscreen SVG rendering

The above is a small multiples chart showing 284 timezones at five year increments. The horizontal axis (for each mini chart) is a calendar year, while the vertical axis is the offset from UTC. Timezones where there is a single ‘clock’ change in the year are coloured green, two changes in red (typically denoting daylight saving) and blue for three or more.

In 1900 the timezones are ‘smeared’ across the chart, few are multiples of an hour, with the gap from 0 to -3 indicating the largely uninhabited Atlantic Ocean. Over time, the timezones start to adopt hourly multiples and in 1920 we see daylight saving start to emerge. Later, in 1945, we see a whole host of one-off changes due to the Second World War.

Let’s take a close look at the details.

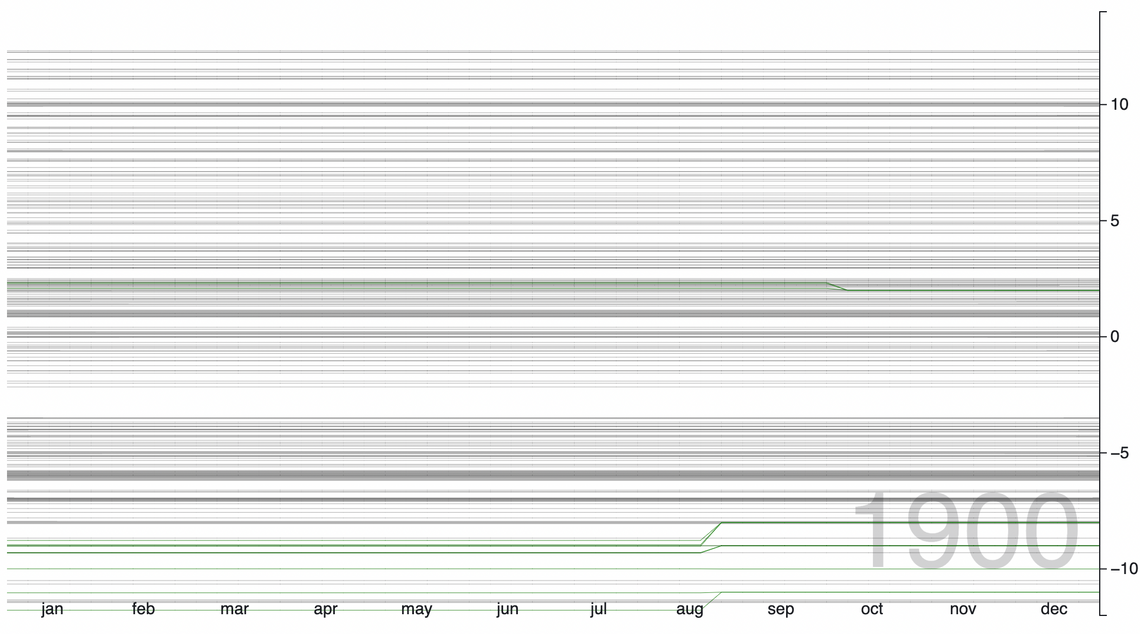

1900

In 1900 this dataset of 282 named timezones indicated 220 different offsets (from UTC), and while some of these were integers, (e.g. Europe/Prague, Europe/Rome), the majority were not - for example Moscow was 2 hours, 30 minutes and 17 seconds ahead.

In this year, a few countries moved to more manageable integer offsets (e.g. America/Yakutat transitioned from -9:18:55 to -9:00), a trend that continued in the following years.

While the IANA timezone database applies rules via the concept of zones, in reality, this isn’t a fair representation of how time was managed in 1900. For many people across the globe, time was set locally within towns or villages, synchronised via a church or town hall clock, set to midday when the sun hit its peak.

When there was little travel, these diverse and ever-shifting, local times were largely sufficient. However, with the introduction of railroads, which required timetabling, this started to become a major issue. “Fifty-six standards of time are now employed by the various railroads of the country in preparing their schedules of running times”, reported the front page of the New York Times on April 19, 1883.

In 1878, Sir Sandford Fleming, a Scottish railway engineer, sought to address this by proposing a system of 24 discrete timezones at one-hour increments, each labelled by a letter of the alphabet, all linked to the Greenwich meridian (an arbitrarily selected line from which all timezones are offset). While a meridian based in Greenwich was soon adopted, timezones were generally considered a ‘local’ issue, with different regions applying their own standards.

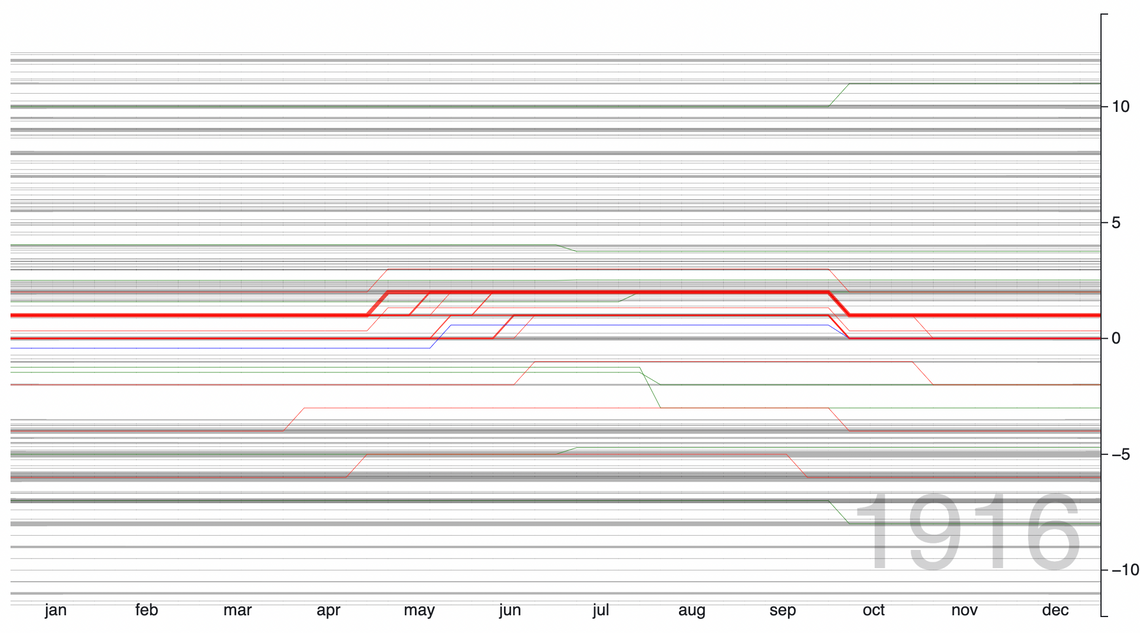

1916

Daylight saving time emerges …

The overall concept of daylight saving is quite simple, seasonal variations cause the sun to rise and set at different times of day. By shifting the clocks forward, then back again, with the seasons, we are able to maximise the amount of daylight within a ‘working day’, which has a number of perceived benefits.

Before daylight saving as a concept was developed, people would simply ‘get up early’, a notion famously associated with Benjamin Franklin and his proverb “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise”.

The first place to adopt daylight saving was the municipality of Thunder Bay (Canada) in 1908. The concept was proposed by a business man, John Hewitson, who petitioned the local councils on the social and economic benefits this would bring. The idea did not catch on globally until the German Empire introduced daylight saving in 1916 in order to minimize the use of artificial lighting to save fuel for the war effort.

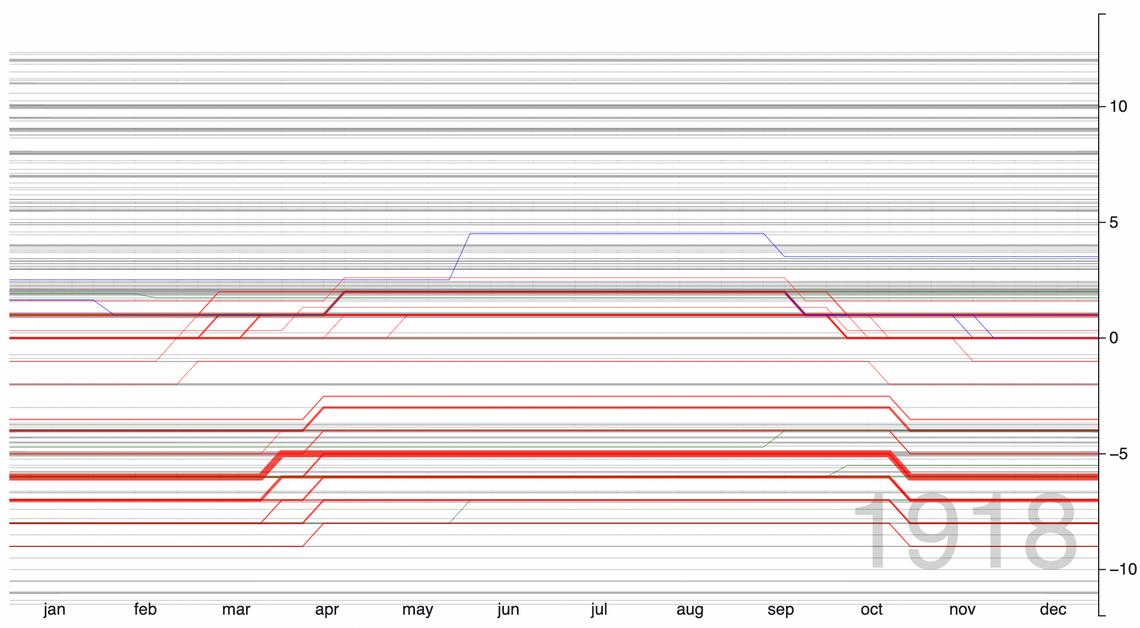

1918

Shortly afterwards in 1918 we can see that much of America adopted daylight saving as a result of the Standard Time Act.

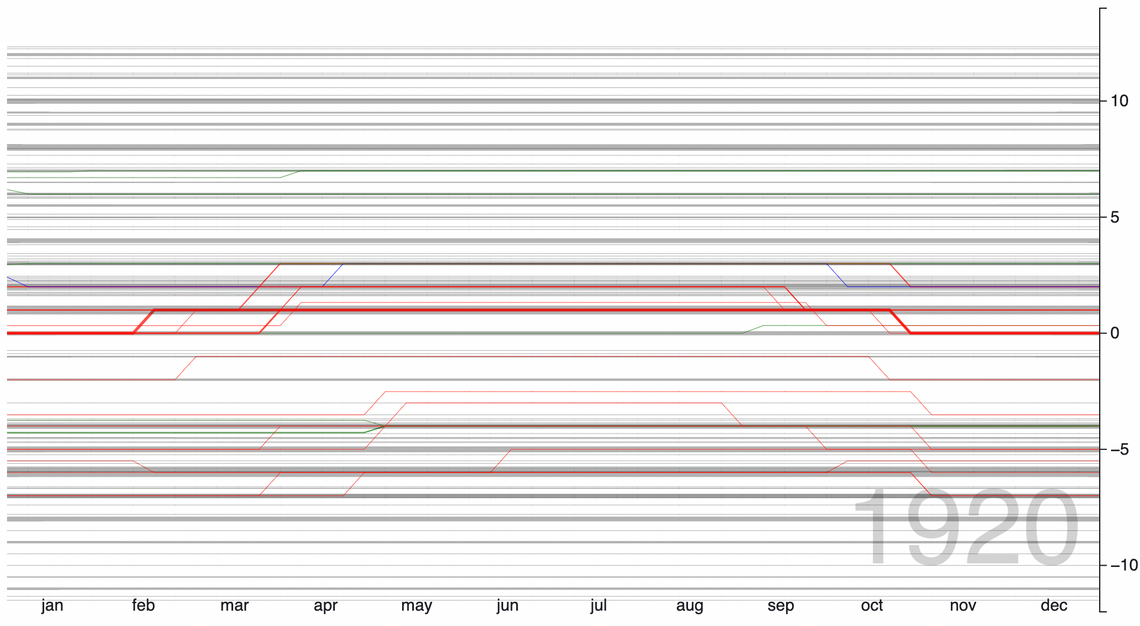

1920

However, this proved to be so unpopular that just a year later the act was repealed!

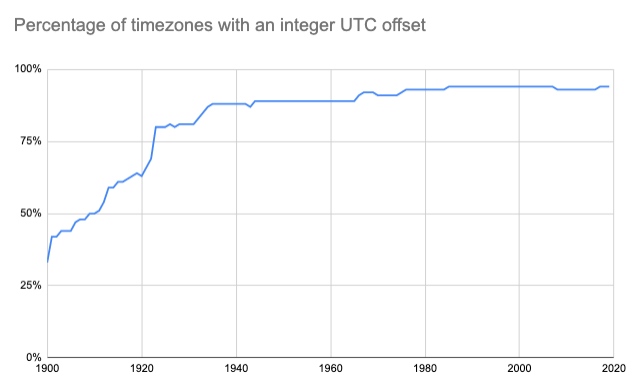

While the concept of daylight saving might not have got off to a great start, the number of timezones with non-integer offsets was decreasing considerably. The following chart shows the percentage of timezones with integer offsets over the past 120 years:

1941

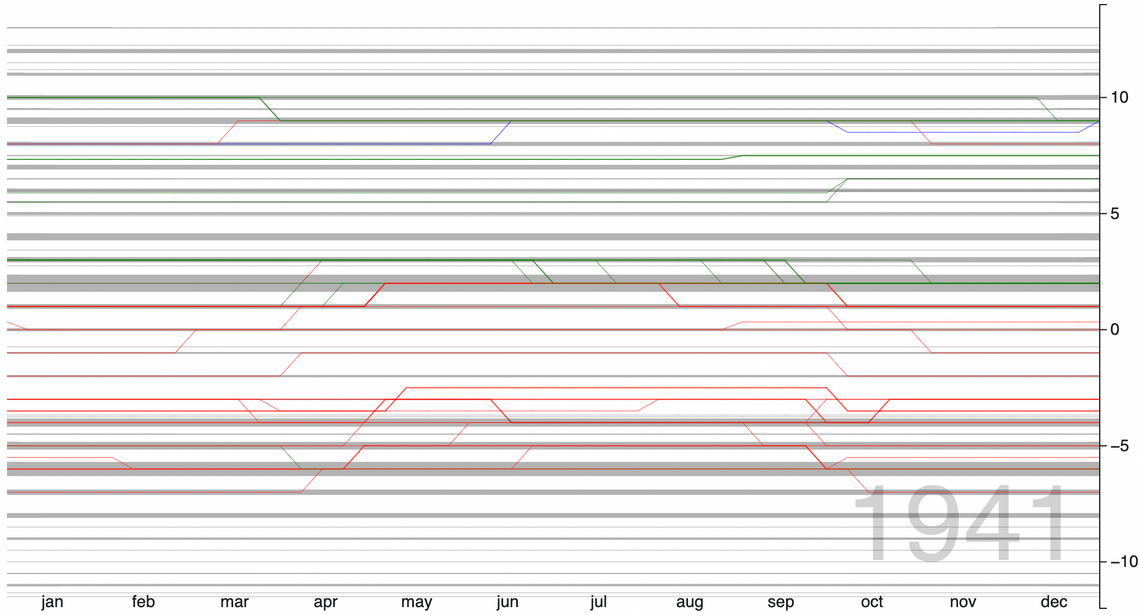

Once again, it was war that had a significant impact on global timezones. In the summer of 1940, the German military authorities switched the occupied northern part of Metropolitan France to +2 (German summer time). Elsewhere, soviets captured Lithuania, and moved it to Moscow’s timezone, a shift of 2 hours, in June 1940.

By 1941 we can see a thick band that represents the German empire:

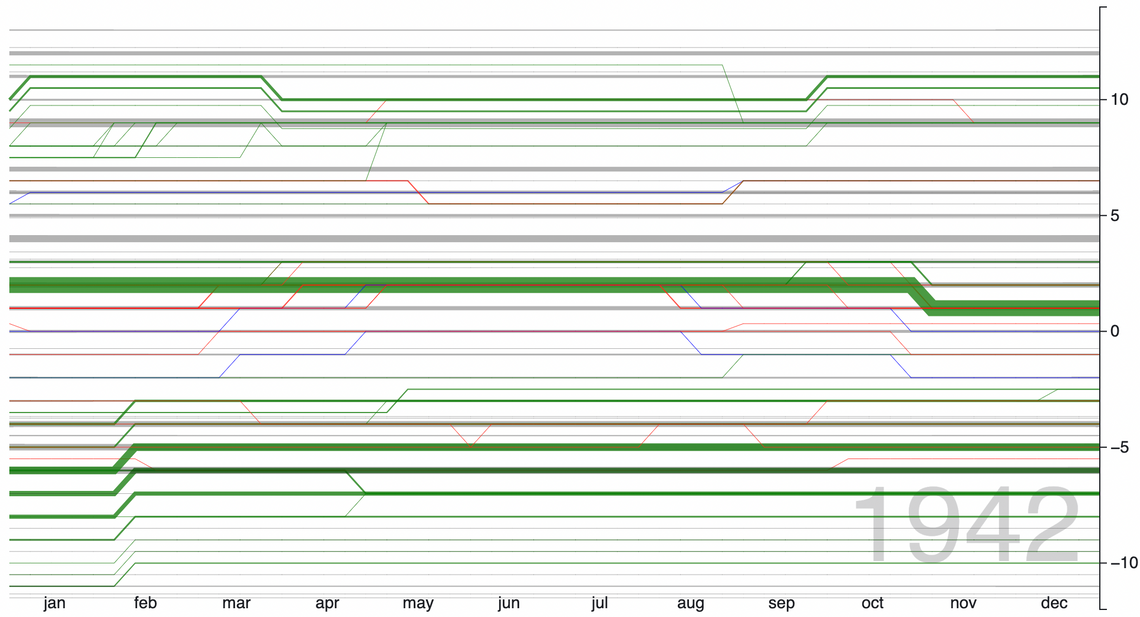

1942

A year later, still within World War Two, we can see the impact of german occupation, when in the Winter of 1942 much of Europe moved to the same winter time

Following the Second World War, timezone changes seemed to settle down a bit.

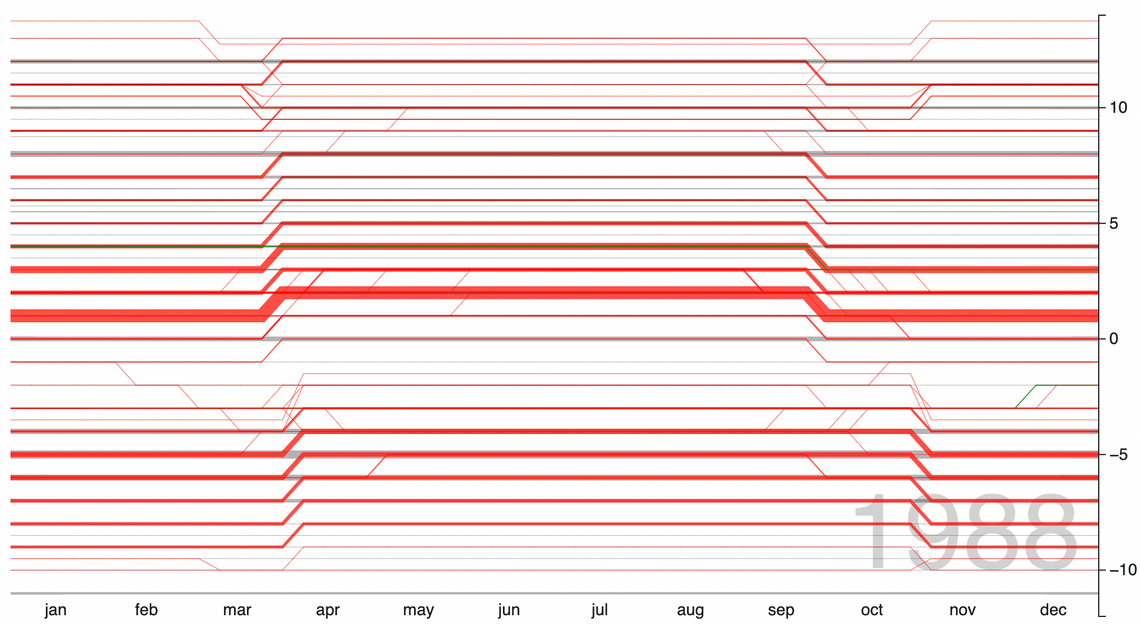

1988

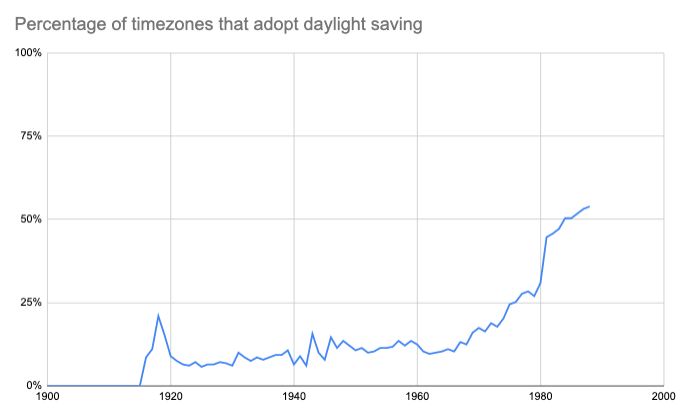

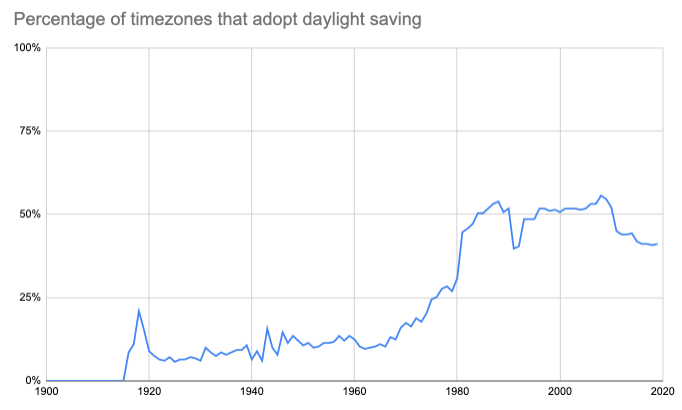

Over the next few decades, daylight saving was gradually adopted across the globe, and by 1988, this pattern was followed by 54% of timezones:

By 1988 we see that a large number of European timezones (that big red band across the chart), were aligned:

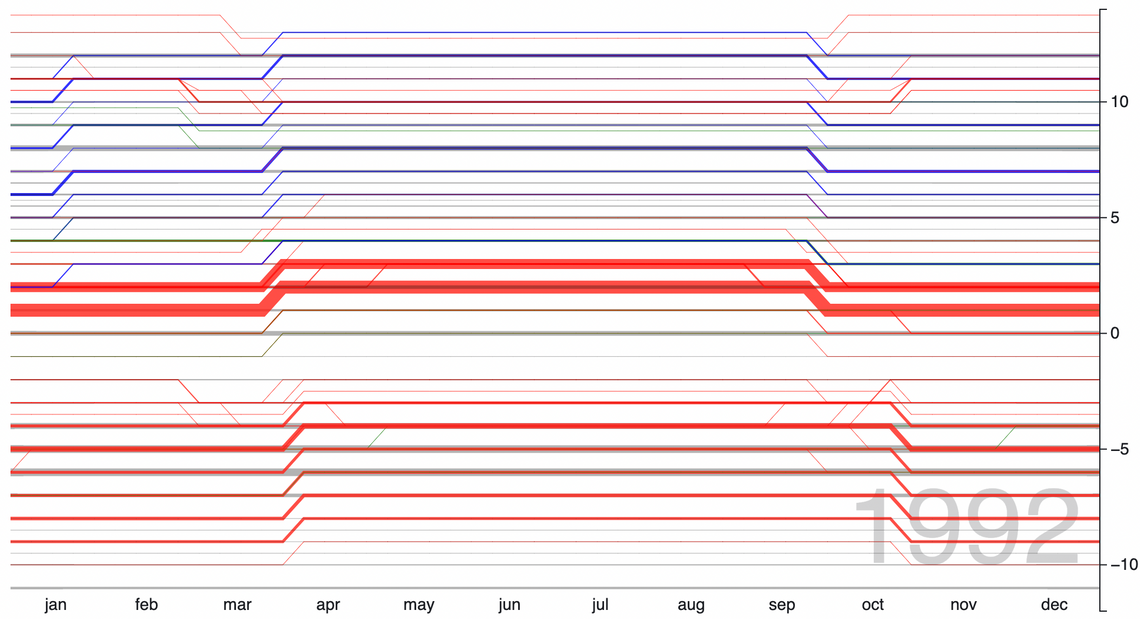

1992

However, shortly afterwards, much of Asia and Russia make multiple clock changes throughout the year, and ultimately abandon daylight saving.

Looking at the chart up until present day, we can see that currently just 41% of timezones have daylight saving:

I am quite certain that this will further reduce over time.

The evidence in favour of daylight saving is somewhat flimsy, based on arguments from the tail-end of the Industrial Revolution, whilst there is growing evidence that it no longer makes sense in the Information Age. A 2016 study found that the economic impact of Daylight Saving, due to increased heart attacks, workplace accidents and cyberloafing (slacking off at work!) cost the US economy $434 million each year, there are a great many others that present similar evidence.

In 2019 the European Union voted to abolish daylight saving in 2021, similarly the “Sunshine Protection Act of 2021” is gaining traction in the US. Over the next decade I feel quite sure that most of the globe will reject daylight saving entirely.

From a developer perspective, abolishing this somewhat dated practice is going to make my life just a little bit easier - but there is more than enough complexity in date and time handling, that will likely never go away!

If you want to explore the data for yourself, there is an interactive version on GitHub.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief exploration of the last 120 years of timezones as much as I have. Now it’s time for me to get back to assemblyscript-temporal-tz and finish the job!

Regards, Colin E.