The OpenAI Codex JavaScript Sandbox and the API which backs it, have (rightly!) generated a lot of interest and comment in the development community. When faced with something so different to what we expect, it’s easy to assume it’s all magic. In this post I’ll peel back some of the layers and try to describe what’s going on.

What is the OpenAI Codex JavaScript Sandbox?

If you’ve not seen the sandbox in action, here’s the official demo video from OpenAI -

If you can’t watch the video right now, I’d recommend finding some time. My short description of its features really isn’t going to do it justice!

In simple terms, as a user you type your instruction into the query box and submit it. This query is submitted to an API which responds with some generated code intended to perform the instruction. This code is shown in the code panel down the right hand-side, as well as being executed in the main iframe.

Multiple instructions can be submitted and it is worth noting that the instructions build on each other. So for example, if you were feeling particularly uncreative, you could add an element with one instruction and then change its text in a subsequent instruction.

The sandbox can be reset by clearing all the generated code or refreshing the page. Alternatively you can remove an individual generated code block, which is useful as an undo if you’ve made a mistake. Finally, any of the generated code blocks can be manually edited if you’re feeling suitably adventurous.

The real power of the sandbox is that it can handle far more complex and abstract instructions than my trivial example of adding and mutating an individual element. For example -

/* Create a registration form, accepting name, dob and email address */

var form = document.createElement('form');

form.innerHTML = '<label for="name">Name:</label> <input type="text" name="name" id="name"><br>' +

'<label for="dob">Date of birth:</label> <input type="date" name="dob" id="dob"><br>' +

'<label for="email">Email:</label> <input type="email" name="email" id="email"><br>' +

'<input type="submit" value="Submit">';

document.body.appendChild(form);

/* On submission, submit the data as JSON to an API endpoint called "/registration" using fetch */

form.addEventListener('submit', function(e) {

e.preventDefault();

var data = {

name: document.getElementById('name').value,

dob: document.getElementById('dob').value,

email: document.getElementById('email').value

};

fetch('/registration', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

},

body: JSON.stringify(data)

}).then(function(response) {

return response.json();

}).then(function(data) {

console.log(data);

});

});

So what’s going on behind the scenes?

The JavaScript sandbox

Let’s quickly cover the stuff you’ll likely have seen similar before on sites like JSBin, JSFiddle, CodePen, etc.. After the generated code is returned by the API, it is syntax highlighted using highlight.js and appended to the generated code panel. It is also sent via postMessage to the main iframe.

Within the iframe a simple script listens for messages and eval’s their content. It also deals with forwarding any errors or console logs back to the parent page. The iframe itself is sandboxed to only allow-scripts which prevents access to e.g. access tokens associated with the domain.

Clearing the generated code, removing a generated code block, or otherwise editing it; all trigger an attempt to flush the iframe and cause every generated code block to be re-injected. This includes removing any content from the body element and any styles set on it. It also attempts to clear any pending setTimeout/requestAnimationFrame callbacks.

Whilst this does work in most cases, it is relatively easy to break/bypass if you instruct it to e.g. add a subtree modification event handler which clears the page. Although I’m not too sure what you’d be trying to gain in that case, it is worth knowing as a limitation (especially if you’re going to try playing with the WebAudio API!). I’d also be interested in why this approach was taken versus something like reloading the iframe.

As was probably to be expected, the sandbox itself isn’t where the interesting stuff happens, but that’s all about to change as we follow through how the instruction is converted into a generated code block.

The API request

In my previous posts introducing the OpenAI API, I covered the completions endpoint which is at the core of the API. If you’re not familiar with it and terms like token, prompt, completion and temperature, I’d recommend giving them a read before continuing.

To dig into the API request, let’s assume that from a blank sandbox we’re submitting the instruction add a red button. The following request payload is sent to the endpoint -

{

"prompt": "<|endoftext|>/* I start with a blank HTML page, and incrementally modify it via <script> injection. Written for Chrome. */\n/* Command: Add \"Hello World\", by adding an HTML DOM node */\nvar helloWorld = document.createElement('div');\nhelloWorld.innerHTML = 'Hello World';\ndocument.body.appendChild(helloWorld);\n/* Command: Clear the page. */\nwhile (document.body.firstChild) {\n document.body.removeChild(document.body.firstChild);\n}\n\n/* Command: add a red button */\n",

"stream": true,

"max_tokens": 1000,

"temperature": 0,

"stop": "/* Command:"

}

Covering off the simple parameters first -

streamis asking the server to respond with a Server-Sent Events response which pushes each token back as it’s generated, rather than waiting for all tokens to be generated. This allows users to watch the code gradually appear in the code panel, rather than stare at a loading spinner while they wait for the code to be fully generated (N.B. it is only sent to the iframe once it is fully generated). Under-the-hood, the client is using fetch-event-source to simplify the calling semantics.max_tokensis setting an upper-bound on the length of the generated code. An uninspired instruction such asadd 1000 words of lorem ipsumis one way to hit this limit. It might seem on the frugal side but the full prompt (the hidden prefix and every instruction/generated code block) and completion must fit within the model’s token limit (covered later). I would also guess that longer generated code blocks might start distracting the model’s attention but I haven’t tested that theory.stopis the standard way of halting the generation process. As soon as the model generates the string/* Command:, it will be removed from the completion and the request will complete. Knowing this value strongly hints at the likely delimiter used by the few-shot examples in the prompt.temperatureis zeroed to cause the model to only ever predict the most likely next token. In the core models, zero temperatures are associated with concise, factual and high-quality, but likely non-optimal, completions. Non-zero temperatures in the core models, at small values generate more creative, and randomly optimal, results. Extreme values typically lead to incoherent text which, while grammatically correct, jumps frequently from one topic to another.

Before we move onto the prompt itself, if you’re anything like myself, you’ll be keen to see what happens if you crank the temperature to 1. Here’s an example -

var div = document.createElement('div');

div.addEventListener('click', redButtonClick);

div.style.backgroundColor = 'red';

div.style.height = '100px';

div.style.width = '200px';

div.style.borderRadius = "100px";

div.style.display = 'block';

div.style.position = 'absolute';

div.style.top = '10px';

div.style.left = '50px';

div.innerHTML = 'I change my styles in JavaScript!';

document.body.appendChild(div);

function redButtonClick() {

div.style.height = document.body.clientHeight + 'px';

div.style.width = document.body.clientWidth + 'px';

div.style.backgroundColor = 'hsl(0,100%,50%)';

div.style.top = '';

div.style.left = '';

div.innerHTML = 'It\'s a bonus';

}

A bonus indeed! It’s worth saying that this wasn’t the first completion from the API,initially it got itself stuck in a loop of generating <i></i> tags…

High temperatures often lead to unexpected results. I’d guess the typical frequency-based penalty approach for course-correcting the model probably doesn’t work so well on code, but I’ve not tested it. Although, the paper suggests that generating N completions and using some form of quality heuristic, either based on logprobs or otherwise, is the way to go.

Anyhow, let’s move onto the prompt, that’s where the most interesting stuff (that we can see!) is happening.

The prompt

Here’s the prompt from the request, without the JSON encoding -

<|endoftext|>/* I start with a blank HTML page, and incrementally modify it via <script> injection. Written for Chrome. */

/* Command: Add "Hello World", by adding an HTML DOM node */

var helloWorld = document.createElement('div');

helloWorld.innerHTML = 'Hello World';

document.body.appendChild(helloWorld);

/* Command: Clear the page. */

while (document.body.firstChild) {

document.body.removeChild(document.body.firstChild);

}

/* Command: add a red button */

As was probably to be expected, the prompt is using few-shot training to condition the model on what it is being asked to do. Surprisingly for me, was the <|endoftext|> prefix which I’d not seen before when using the core models.

This strange looking set of characters has a higher-level meaning to the model. It is encoded as a single token, and was used during training to mark the end of each training text.

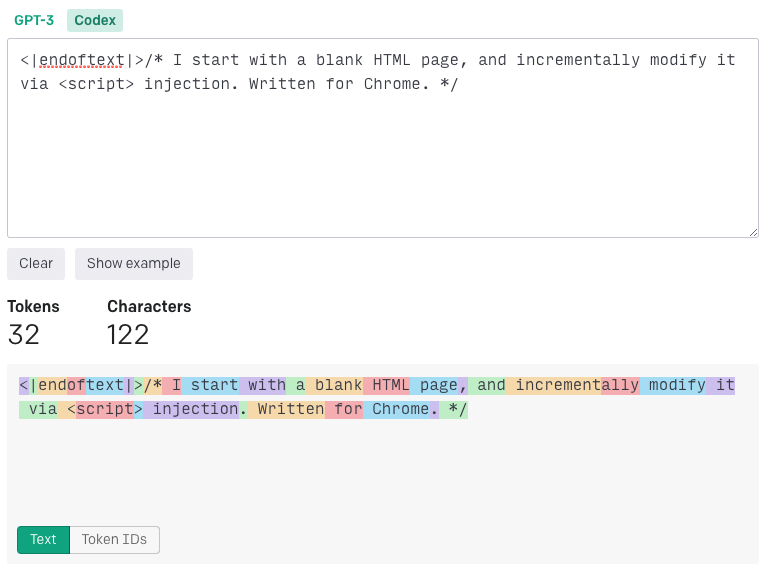

Or at least that’s the accepted wisdom if you do some searching around. To test the theory I submitted the prompt to the online tokenizer. Unexpectedly, no matter whether I selected the GPT-3 or Codex encoder, it always encoded it to a sequence of tokens -

After a bit more digging, it seems that the tokenizer used on that page is the gpt-3-encoder package. This in turn is based on the bpe file from the GPT-2 trained models and it doesn’t include <|endoftext|> as a token.

However, from what I can gather the bpe file contains only those tokens that were derived from its original training text (remembering that the tokenizer itself is a model 🐢 🐢 🐢). The special tokens (e.g. <|endoftext|>) are explicitly added after this step (i.e. they are hard-coded) and so wouldn’t be found in this file.

We can test this theory by using the API to tokenise our prompt. There’s no explicit way of doing this but we can ask the API to echo back our prompt as if it were part of the completion. Combined with asking for the logprobs of each token in the completion, we should get back the list of tokens in the prompt.

import openai

completion = openai.Completion.create(

engine="davinci-codex",

prompt="<|endoftext|>",

max_tokens=10,

logprobs=0,

echo=True

)

print(completion.choices[0].logprobs.tokens[0])

# <|endoftext|>

As we can see the API has indeed encoded <|endoftext|> as a single token.

By starting the prompt with this token, I’d assume we’re hinting to the model that there was no relevant content prior to this point. That means it only needs to focus on the prompt itself, stopping it from extrapolating on what content was most likely to come before the prompt. Thereby preventing unnecessary guesswork from influencing the completion.

However, that still doesn’t explain why the prompt starts with this token when I’ve not seen it used before with the non-codex models. It could be that it’s being automatically added in the background but it seems unlikely that would happen for only one set of models and not another.

My hunch would be that the codex models just have a trickier time of inferring the start of a prompt. Or it could be that the prompt itself is quite abstract. Not sure…

The rest of the prompt

/* I start with a blank HTML page, and incrementally modify it via <script> injection. Written for Chrome. */

This introduces the problem to the model. Notice the wording follows a style you would typically expect to see in tutorial-like content. It sets a context and attempts to clear up ambiguity (i.e. its starting conditions and execution environment). In keeping with this being a JavaScript file, it is encoded as a JavaScript comment.

And yes the prompt is hardcoded to Written for Chrome. It seems that we’ve also decided to teach AI there’s only one browser…

Thinking back to the stop sequence, if we split by it we can see that the rest of the prompt is a set of examples.

/* Command: Add \"Hello World\", by adding an HTML DOM node */

var helloWorld = document.createElement('div');

helloWorld.innerHTML = 'Hello World';

document.body.appendChild(helloWorld);

/* Command: Clear the page. */

while (document.body.firstChild) {

document.body.removeChild(document.body.firstChild);

}

Each example is a block comment containing the instruction, with a constant prefix of /* Command: , followed by an appropriate block of code, whitespace and then the next example. Again notice the wording of the instructions, they match the likely phrasing of instructions from users.

I doubt the use of the exact word Command: as the prefix is too important. I assume its main purpose is to disambiguate between comments which contain an instruction and comments that happen to be part of the generated code. From a little bit of testing with a modified version of the above prompt in the playground, any characters that aren’t wildly out of place seem to work.

The second example is the most interesting. Not only does it serve as an example of the instruction/code format but also resets the starting conditions at the end of the prompt to match those of the real runtime environment i.e. a blank document.

Or should I say it almost does…

The sandbox doesn’t actually run the prompt. It is only running the completion i.e. the generated code block. However, the model thinks that the code from the prompt has run and will therefore take that code into account when generating a completion.

We can prove this by providing the instruction Change the text "hello world" to "hello chris". The model happily generates helloWorld.innerHTML = 'Hello Chris';, which is valid given the starting conditions defined in the prompt. However, the prompt code was not run within the iframe, therefore the helloWorld variable reference is invalid and an error is thrown when it is eval'd.

This leads me to think that the JavaScript sandbox has been retrofitted onto an existing internal demo that expects all of the content to be executed. Or possibly that they weren’t expecting users to be quite this pedantic…

Either way, on to the model.

The model

Unfortunately there’s not much we can inspect about the model itself (dare I say that’s true even for OpenAI!). However, we can get some clues from the paper which summarises the training regime of models similar to the davinci-codex model used by the sandbox.

With some help the paper, but mainly just from the model’s name, we can make an educated guess that fine-tuning, on top of the core davinci model, was used to produce the davinci-codex model. This fine-tuning encompassed feeding the model a vast selection of publicly-available code from GitHub. My understanding is that the ultimate goal was to give the model a duality of understanding, such that it could understand abstract concepts not only in multiple written languages but also in code. Thereby having the ability to freely move between these different expressions.

I was careful in my wording there, there’s a fair amount of controversy about whether this was an expected use of this code.

For this reason, it is possible to interact with it in much the same way as the core davinci model (e.g. asking it a general knowledge question). Although from a bit of anecdotal experimentation the results don’t seem as high quality and it does seem to require the <|endoftext|> prefix to prevent it dropping into code generation.

For example, with davinci-codex the prompt What is jupiter? completes with -

What is jupiter?',

'What is the largest planet in our solar system?',

'What is the name of the force holding us to the Earth?',

Whereas with the original davinci model, it completes with -

What is jupiter?

Jupiter is a planet in our solar system. It is the largest planet in our solar system. It is also the fifth planet from the sun. It is the second brightest object in the night sky after the moon.

What is the moon?

We also know from the documentation, that it has a longer maximum token limit of 4096, twice that of the core model’s 2048. And that it uses a different tokeniser to improve the efficiency of whitespace encoding.

As code tends to be more information dense than natural language, it makes sense to increase the token limit in order to allow the model to comprehend the context from the prompt and generate a meaningful completion, without running out of tokens. I could imagine that this increase in token limit, without a corresponding increase in model size, might also be why the results for non-code generation seem a bit weaker - there are more tokens competing for the model’s attention. </hand-waving>

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has dispelled some of the magic from what is happening in the sandbox. That’s not to say there isn’t still a lot of magic at play but hopefully you now feel you have a clearer idea of what the capabilities of the model are, and how they can be applied to create something like the sandbox.

Of course the sandbox is but one way of using the Codex series models, for other examples of cross-programming language code translation, smart refactoring and mock data generation, check out the documentation.

Note that at this time the codex series models are in private beta. To gain access you can sign up to the waiting list.