Performance is a relatively ambiguous term without having a clear definition of what our goals are. In this post I wanted to side with latency being a key indicator of performance by exploring a concurrency library called the Disruptor. The Disruptor was developed by LMAX to improve Java inter-thread communication and is mostly suited towards applications that are on the high to extreme end of latency sensitivity, maintaining high throughput while ensuring very high response times. Typically such services look to reduce response times between the consumer and producers to as low as 1ms or less and in the most extreme cases dwindle down to hundreds of microseconds. I will try to outline what is the Disruptor, describing some of the problems it solves, what we can learn from the Disruptor and deliberate whether we should be using it to build some of our applications.

Context & Background

We often hear that the applications we build need to be scalable, highly available, fault tolerant and performant. In my experience, people often tie performance and horizontal scalability to each other. If we have the ability to scale out to multiple concurrent services, then we can improve the throughput or the number of transactions handled per second in a system and often gain fault tolerance at the same time. However, sometimes this is not good enough. There are only so many lanes you can build on the motorway before fundamentally the speed limit is the bottleneck. In aggregate we may be able to achieve many thousands of transactions per second but what if 1-2% of those transactions were unacceptable slow? Some niche applications like those in High Frequency Trading firms and financial exchanges require as many as millions of transactions per second and the speed of each and every individual transaction really does matter. It’s at this point horizontal scaling may no longer be helpful when handling worst case latency in applications. Decisions around transport, the threading model and what data structures you choose now start to have a much higher weight and a greater impact on overall performance.

Why Java and is Java performant?

Why are we considering Java as a viable option for low latency in the first place? For many High Frequency Trading firms and Hedge Funds out there, many of them know that the latency is a key indicator for performance and will therefore focus on using FPGAs to reap the very fastest latencies at the hardware level. FPGAs are able to do this because they are able to completely bypass the OS. The problem is that a strategy built largely around the hardware can make it difficult to respond to change in a rapidly changing environment in the same way that higher level languages like Java can. It is also not particularly easy to find the necessary skills for engineers to work on such systems compared to finding a knowledgable Java software engineer for instance.

One major source of nuance and criticism when using Java for low latency is the Garbage Collector but there are many different techniques that can be used to either minimise or completely eliminate this. Recent developments around ZGC for example are very promising and could mean GC pause times will eventually reduce to less than 1ms. If that was not good enough, no-GC code or going off-heap are still options and there are even commercial offerings like AzulZing which claims to be a “pauseless” JVM. The latter two options for extremely low latency (less than 1ms response times) are probably more necessary.

While some of these options are a bit more complicated than others Java is still a trusted and robust option with a thriving community behind it while still fulfilling most low latency demands.

What is the Disruptor?

The Disruptor framework was developed by LMAX, a financial exchange, as far back as 2011 to reduce the latency produced by inter-thread communication through a series of optimisations. LMAX noticed most of the bottlenecks in their systems were related to queues between workers in their staged pipeline and wanted to do something about it. The Disruptor was proposed as an alternative to traditional queues in Java such as the ArrayBlockingQueue, while providing similar in-order and multi-cast type semantics supporting multiple producers and consumers. Their analysis concluded that locking in queues is expensive and prone to a lack of memory efficiency. They found that with some optimisations they could use CPU caches more efficiently and dramatically improve the time between sending and receiving messages. Since 2011, other frameworks such as Chronicle Queue have emerged which is an IPC library which tackles latency between JVM processes but it does not seem to solve the same problem.

On the surface, it would appear as though there have been limited innovations in recent years around ultra low latency. Honestly, the Disruptor itself has slipped a bit under the radar and out of fashion. Perhaps partially because of how unique the demand is for low latency applications of this magnitude. Irrespective of this, I find the combination of the benchmarks reported and the simplicity of the library itself 10 years on still to be very impressive. By understanding some of the core concepts behind the library we can learn to become better developers. Even log4j (a very popular Java logging library) uses the same framework to achieve asynchronous logging which also caught my attention.

What problem does the Disruptor solve?

Let’s start with what the Disruptor is not. It does not solve network or transport latency issues, there are a couple of libraries which focus on both fast and reliable communication such as Aeron, Tibco RV and Chronicle Queue mentioned earlier for UDP unicast, UDP multicast and inter-process communication which are all worth considering for this purpose. The Disruptor is housed purely inside a single process and is not to be used between disparate systems over a network or between processes.

The Disruptor is also not an alternative to some common messaging technologies that are very popular in the wider industry today designed for high availability, resiliency and scalability such as Kafka or ActiveMQ. Again those operate over the network, but they are also more aligned to providing durable, fault tolerant event sourcing and data pipelines. Aside from that these options do not focus on the same order of scale when talking about latency and are more concerned with fault tolerance and availability. Chronicle Queue an IPC framework on the other hand does offer a viable ultra low latency alternative for messages over a network while providing some of the guarantees of a usual messaging framework. Most certainly that’s a post for another day!

The Disruptor targets problems with internal latency in Java processes. It is not a persistent store, messages are stored entirely in memory and it is primarily designed for improving the latency between two or more worker threads acting as either producers or consumers. It is a speedier choice over the ArrayBlockingQueue which is the standard thread safe class in Java for such a task. If you are dealing with a high throughput system that also needs to guarantee that every message needs to be delivered as quickly as possible then this library starts to look promising.

Why is the Disruptor Fast?

There are multiple reasons why the Disruptor is so fast. I have tried to summarise some of the core reasons.

1. Lock Free

Locks are at the heart of some performance issues. Using a ReentrantLock or synchronized in Java has three major side effects:

- A lock will block other writers and perhaps on the whole collection if the granularity is not finely tuned

- The OS during a lock may choose to context switch between threads thus providing less time for our application to do useful work

- The L1-L3 CPU caches become invalidated as new variables and operations are loaded with new instructions from other context switched activities. We want to optimise for cache hits wherever possible (more on this later)

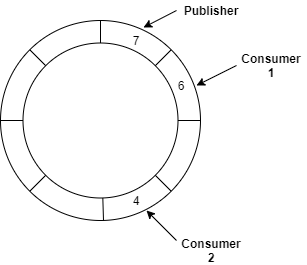

The LMAX team observed that when using queues in general they are often either close to being either completely full or empty. This is because producers and consumers rarely operate at the same rate and are seldom in balance. Locking occurs at the head and tail nodes which means we can see some contention and some of the problems mentioned above. The good news is when the Disruptor is configured with one publisher and one-to-many subscribers it is completely lock free. This is achieved by their ring buffer implementation combined with a number of offsets or “sequencers” into the actual buffer.

So how does this circular buffer solve my locking issues you ask? Well these sequencers have some special characteristics.

To maintain a lock-free data structure we need to consider mutual exclusion and visibility due to problems with Race Conditions and Cache Coherency. Essentially, updating sequence numbers must happen exclusively in one thread while the sequence numbers of both publishers and consumers need to remain visible and up to date within each producer and consumer thread. So let’s explore these areas a bit further.

Mutual Exclusion

The Disruptor achieves mutual exclusion by largely abiding to the single writer principle where possible, if there is only one writer then there are no other writers to contend with for write access. A publisher claims the next sequence number in the buffer without a lock as it is the only writer that will need to update it. Solving the mutual exclusion problem can be this simple but if there are multiple producers a different strategy is needed. Where there are multiple producers, Compare and Swap operations or AtomicLong can be used which are still more performant than a standard lock, ensuring a sequence number is still committed exclusively without race conditions arising. Compare and Swap operations achieve this by eliminating the need for the OS to context switch between threads. By using AtomicLong instead of yielding to other tasks the thread will continuously attempt to update the value of a sequence number and compare the actual result with an expected one until they match. Note, this will not be as fast as a single producer without locking.

Visibility

With respect to visibility, each sequence number from a publisher is updated through the use of memory barriers/fences. Trisha Gee provides a brief description of how this works here. At any time the CPU may choose to re-order CPU level instructions for optimisations which can lead to visibility issues with threads holding different values for sequence numbers. Memory barriers are the solution to this problem and are enforced by the volatile keyword in Java. A write memory barrier provides us with a happens-before guarantee to ensure all writes to this variable are flushed to the cache being read again. A future read from a volatile variable will then truly have the latest value in memory and any write to this variable is propagated to all CPU caches. This ensures consistency across all other running threads.

The downside of the volatile keyword is that there is still a performance hit when values are propagated. To mitigate this impact, reads and updates to such sequence numbers are done in batches where possible. With memory barriers in place, we can use a strategy within the library which will wait for a slot to become committed by the publisher before a consumer can do further work on that event. There are then multiple strategy classes to do this within the library such as a BusySpinWaitStrategy or a YieldingWaitStrategy as some examples. Some will induce less “jitter” or latency spikes but can come at the expense of CPU usage and there are others which try to make more of a trade-off.

2. Optimising for CPU Cache Lines

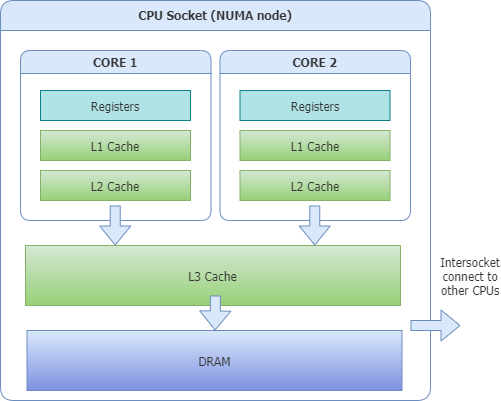

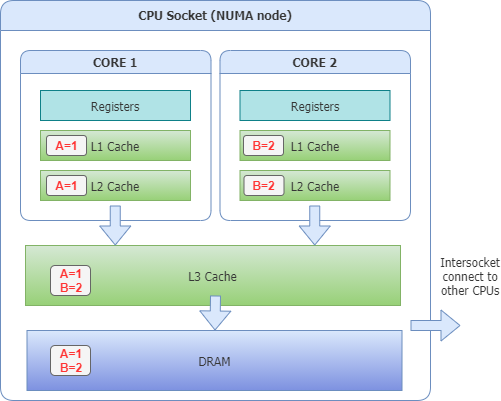

To get a sense for what Cache lines are it is best demonstrated by a diagram. So here is one.

As you can see each CPU core typically has L1 and L2 cache to itself while L3 is shared between cores. L1 cache is the speediest to perform operations but is also the smallest. L2, L3 follow the L1 cache in increasing size but decreasing speed. We really want to optimise to get as many cache hits as possible on the fastest hardware.

The problem is a cache line will consist of a 64-128 byte contiguous block in the cache and this gives rise to issues related to locality. Variables stored and updated within the same 64 byte block will trigger cache invalidations for multiple strands of data and increase overall latency. It is entirely possible that two entirely independent variables being read and updated on two entirely different cores may invalidate the same cache entry which they share. When these variables are then accessed, it may have to frequently fetch the latest value from the L3 cache even when the value has been unchanged. If you can picture our producers and consumers continuously updating values to different variables it is not hard to see that they will generate this kind of latency unintentionally. This constant invalidation of caches does not serve our needs very well.

There is a price we pay for trying to ensure consistency between these different caches but a necessary one for visibility of values between all working threads. However, there is no need to update another cache on the CPU if the value we are updating is not related. This specific problem is known as False Sharing. The Disruptor avoids this issue by padding individual variable declarations with 64-128 byte of variables, so that’s 8 long variables. This ensures each variable is on a separate isolated cache line. Java also more recently introduced the @Contended annotation which provides something similar.

private int hereIsMyFirstValue = 5;

private long p1,p2,p3,p4,p5,p6,p7,p8;

private int hereIsMySecondValue = 10;

@Contended

public class MyPaddedClass {

private int hereIsMyFirstValue = 5;

private int hereIsMySecondValue = 10;

}

3. Cache Friendly and Reduced Garbage Collection

As an array based implementation the Disruptor compared to a LinkedList ensures that elements sit within one contiguous block within memory and that elements are pre-fetched/loaded into the local CPU cache. Each logical entry is physically allocated to the next in memory and values are conveniently cached ahead of when they are used. If you compare this to a LinkedList, values are instead distributed widely across the Heap memory when they are allocated so we will lose those valuable CPU cache hits. The ring buffer is also pre-allocated up front with a fixed number of container objects. These containers are reference types or objects so they will reside on the heap but they are re-used over and over once a slot in the buffer is reclaimed. This continuous re-use means that containers live forever and don’t suffer from ‘Stop the World’ pauses performed by the Garbage Collector. That being said, we do need to be mindful that nested values on those objects are kept as primitive values to avoid indirectly allocating to the heap.

Profiling and Benchmarks

The LMAX team have published results that compare the performance of the Disruptor against an ArrayBlockingQueue. Since then it is fairly likely that a bunch of optimisations have been made to the native Java data structures and hardware in itself has come long way over the years. I was interested in how the the performance compares with alternatives today and with code I’ve constructed myself to see the fruits of LMAX’s labour.

This is the machine that I performed the benchmarks on and the JVM specifications:

- CPU: Intel Core i7-1165G7 2.80GHz 12MB L3 cache

- RAM: 16.0GB

- OS: Windows 10

- JVM: Amazon Corretto (Java 8)

- Heap Size: Initial and Max Heap size of 2048mb (-Xms2048m, -Xmx2048m)

- Benchmarking Tool: JMH

For the benchmarks these are the settings/assumptions I made:

- Queues were set-up with a bounded capacity of 2^14 slots. Apart from

ConcurrentLinkedQueuewhich is unbounded. - Counters were incremented a total of 50,000,000 times for all benchmarks of this type.

- 50,000,000 messages were sent on each queue and used for consumption.

- Each test consisted of 10 runs.

- The

BusySpinWaitStrategywas used within the Disruptor. This meant messages were read from a spinning for-loop rather than yielding to other threads. - Single producer mode (without locks) was used with the Disruptor.

Benchmarks Ran

Broadly there are 2 main types of benchmarks that I ran.

- Test 1: A counter that was incremented within a simple for-loop until a certain value was reached. See single threaded example below.

private long incrementCounterNoLock(ThreadRunState threadRunState, Blackhole blackhole) {

long i = 0;

blackhole.consume(sharedCounter);

while (i<threadRunState.ITERATIONS) {

sharedCounter++;

i++;

}

return sharedCounter;

}

- Test 2: A single producer with a single consumer sending and then receiving a long value via a queue. The consumer would do nothing with the value. See Disruptor example below.

public EventHandler[] getEventHandler() {

EventHandler eventHandler

= (event, sequence, endOfBatch) -> {};

return new EventHandler[] { eventHandler };

}

private void produceMessages(ThreadRunState state) {

for (int i = 0; i < state.ITERATIONS; i++) {

long sequenceId = ringBuffer.next();

ValueEvent valueEvent = ringBuffer.get(sequenceId);

valueEvent.setValue(state.VALUE);

ringBuffer.publish(sequenceId);

}

}

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setUp() {

ThreadFactory threadFactory = DaemonThreadFactory.INSTANCE;

WaitStrategy waitStrategy = new BusySpinWaitStrategy();

Disruptor<ValueEvent> disruptor = new Disruptor<>(

ValueEvent.EVENT_FACTORY,

(int)Math.pow(2, 14),

threadFactory,

ProducerType.SINGLE,

waitStrategy);

disruptor.handleEventsWith(getEventHandler());

ringBuffer = disruptor.start();

}

The permutations of these benchmarks then pivoted on using locks/no-locks, using AtomicLong within Java, using a different number of threads and a different queue data structure such as the ArrayBlockingQueue or the Disruptor we’ve outlined here.

It should be noted that I personally have limited experience in benchmarking so take these results with a grain of salt. I have tried to accurately measure these by removing various compiler optimisations such as Dead Code Elimination and Constant Folding, running warm-up routines and running multiple iterations. Those are outside the scope of this post.

Results

Results are below and measured in milliseconds.

| Description | Min(ms) | Avg(ms) | Max(ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incrementing a counter inside a single thread | 132 | 139 | 156 |

| Incrementing a counter with a synchronized block inside a single thread | 9157 | 9399 | 9709 |

| Incrementing a counter with a synchronized block inside two threads | 23331 | 24838 | 25694 |

| Incrementing a counter with AtomicLong inside one thread | 2341 | 2462 | 2621 |

| Incrementing a counter with AtomicLong inside two threads | 4741 | 5011 | 5344 |

| Description | Min(ms) | Avg(ms) | Max(ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50,000,000 messages through the Disruptor (bounded queue) | 2417 | 2500 | 2600 |

| 50,000,000 messages through a ConcurrentLinkedQueue (unbounded queue) | 22240 | 23025 | 24613 |

| 50,000,000 messages through a ArrayBlockingQueue (bounded queue) | 63811 | 67048 | 72803 |

So what do these benchmarks tell us? Overall the results mostly seemed consistent with LMAX findings.

- A single thread without a lock would significantly outperform a single thread with a

synchronizedblock when incrementing a counter. Approximately 60 times faster or more in benchmarks. - Incrementing an

AtomicLonginstead of using a long type inside asynchronizedblock would lead to a 3-4 fold improvement. - The Disruptor performed at least 25 times faster than an

ArrayBlockingQueueand significantly faster than the unboundedConcurrentLinkedQueue.

Certainly if I was developing a system to process millions of messages per second and where latency mattered I would definitely consider using the Disruptor.

What Downsides are there from using the Disruptor?

As mentioned at the very start of this post, “performant” can often take on many different meanings depending on your own goals. What is performant for a financial exchange or High Frequency Trading firm may not apply equally for say a flight booking system. Software Engineering is often about making trade-offs and here are a few reasons why this library may NOT be the right choice for you:

- If scaling horizontally is working perfectly well for you without the need to consider vertical scaling and intricate hardware level operations.

- If messaging is not the source of bottlenecks in your system. There could be much lower hanging fruit in your system yielding higher rewards.

- If you need an Inter-Process Communication library. The Disruptor is designed at solving a different problem for thread communication inside a single process and it won’t help you.

- If CPU usage is equally important. While the library maximises throughput some of the principals behind the Disruptor rely on busy waiting loops which can starve other running threads if you are not careful.

- If your application already suffers from bloat. Adding another library to your application may not be helpful for future maintenance.

- If a thriving community behind a framework is important to you. It is quite difficult to find people talking about this library and the framework itself is rarely updated on GitHub. This could be a sign of stability more than anything but it’s worth keeping in mind that this area is quite niche.

Summary

Hopefully this post provides a brief insight into what is the Disruptor framework and the core concepts behind it which help drive low latency. As with all performance related changes I would suggest benchmarking your application before introducing any changes to ensure they are good choices. While I have tried to go over everything this is a complicated topic so you can always read more in the original technical paper here.