In this post I demonstrate how GPT-3, a new and advanced language model, can construct engaging and unique stories from user-specific data, with relative ease …

Storytelling with data

You can tell powerful stories with data, but so often we are faced with raw data (albeit beautifully presented), and are left to create our own narratives.

If you already have some form of connection to the data, for example it might be the product sales at the company you work for, you are motivated to create your own narrative. In this context, the raw data, effectively presented, is enough. Company performance dashboards, website traffic and application performance metrics are presented in the form of charts and data, with very little supporting text. Because you have a connection to the data, and additional context, you can spot patterns and tell your own stories - for example, how a change in pricing structure affected renewal rates.

However, if you don’t have a strong connection to the data, you are not motivated to invest the time to explore, and create your own stories.

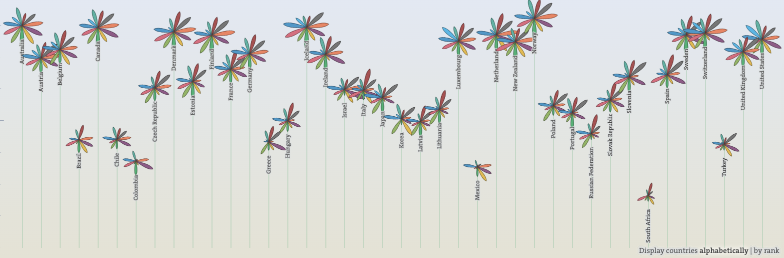

One way to motivate exploration is to make the data visually interesting; even playful. The OECD Better Life Index is an interesting example that allows you to explore data based on the relative weighting of topics. This certainly does makes the experience feel more personal.

The power of combining data and narrative is well understood in the journalism industry. Combining both narrative and data takes up a lot of screen estate, which is why they are often presented as a long-scroll, a story that unfolds with interactive elements triggered as you progress. You’ve likely seen articles in this form from the likes of the BBC, New York Times or Bloomberg. Considering this post is about AI, somewhat topically, here is a story which tracks the usage of an image familiar to people who have studies image processing, and another which provides an introduction to machine learning. There’s even a term that describes this specific presentation style; scrollytelling.

All of the above examples have a single dataset, and a single story. What if the data were more personal? How could we create an accompanying narrative?

Many online services understand that we are interested in our own data, giving us a better understanding of our own behaviours and preferences. Services such as Spotify and Strava (a fitness tracked) allow you to create ‘year in review’ reports at the end of the each year; a fun way to look back on, for example, the music you’ve listened to, or where you’ve run. However, in all cases, they present the raw data itself. Having said that, Strava’s most recent effort was particularly beautiful, as seen in this video.

Running Report Card - v1. Procedural

Last year I wanted to explore the possibility of creating bespoke stories based on personal data, and as a Strava user, I had a go at creating a running ‘report card’. The app, which I launched last year, uses the Strava API to extract the raw data from an individual user’s account. This data undergoes a process of number crunching to extract information such as total mileage, and total elevation gain. It also runs some simple classification logic, for example a user might be rated as a recreational runner if their mileage is relatively low, or a dedicated runner if it is quite high. The app also throws in the odd comparison, for example, comparing their elevation gain to the height of Everest.

This data analysis creates a number of facts, the narrative itself is simply composed of passages of text, with tokens that represent where these facts should be inserted. Here’s a section of the report that describes when the Strava athlete tends to go for runs (e.g. time of day, day of week):

We are creatures of habit, runners more so than most! You're most

likely to find {{ forename }} pulling on {{ thirdPersonPossessivePronoun }}

trainers and hitting the road (or trail) on a {{ mostlyRunsOn }}.

{{ caps thirdPersonPronoun }} tends to go for long runs on a {{ longRunDay }}

and works out on a {{ workoutDay }}. Also, {{ forename }} is {{ timeOfDay }}.

As a result, the structure of everyone’s report is largely the same - there is some branching logic in some circumstances, but for the most-part reports differ based purely on the ‘facts’.

I must admit, I was hoping for something more dynamic, however, when I shared the Running Report Card on Reddit and various other sites, it was well received, and to-date it has generated reports for just over 3,000 athletes.

It was lots of fun developing this app, but I felt I had reached my limit, no amount of if/then logic was going to make each report feel truly bespoke.

That was until I gained access to the GPT-3 …

v.2 Running Report Card - AI-driven

Introducing GPT-3

Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) is the latest language model developed by OpenAI. The job of a language model is quite simple, given a sequence of words (or more accurately tokens), predict what comes next. This is an area of machine learning that has seen a lot of activity recently, and is progressing rapidly. GPT-3 uses a novel technique called ‘attention’, as described in the widely quoted paper “Attention is All you Need”, that allows the model to ‘intelligently’ pick out the most important words (and concepts) within a passage of text.

This new technique, coupled with the vast size of the model itself (175 billion parameters) and the equally vast size of the training corpus (45TB of text from Common Crawl, and more), has resulted in a language model that is a significant leap forwards in capability. GPT-3 has a deep understanding of the English language (and many other languages too) and has knowledge of an incredible number of facts.

Yes, the numbers are impressive, but what I find truly astonishing about GPT-3 is the way that you interact with it.

Prior to GPT-3, using language models would typically involve spending a considerable amount of time creating a training dataset, which would be used to train the model to the specific task you had in mind. However, GPT-3 is general purpose by nature. You want it to perform a specific task? You either ask it directly, or give it a few examples, and it does the rest.

Let’s say you want to build a tool that translates English into French. With GPT-3 you just give it a few examples (in what is termed a prompt):

English: I do not speak French.

French: Je ne parle pas français.

English: See you later!

French: À tout à l'heure!

English: I have a pet cat

From this it understand the task at hand, and provides the following response (termed a completion):

French: J'ai un chat.

That’s it. Amazing.

GPT-3 doesn’t have endpoints for the common language tasks of translation, summary generation and classification. It just has one endpoint, where you tell it (or show it) what you want it to do.

This is a huge leap forwards - it removes the need for picking a model that is specialised for a specific task, and removes the need to train (or fine tune) for your dataset.

There’s much more to be said about how GPT-3 works. If you’re interested in a guided tour of the API and its capabilities, I’d recommend the GPT-3 primer which my friend Chris Price wrote, I found it really useful.

Creating personal data stories with GPT-3

Returning to the Running Report Card, I wanted to see whether GPT-3 could be used to generate the narrative elements of this report. I’m happy to say that it was more than capable.

My previous approach was to have passages of text with tokens that are replaced by ‘facts’ derived from the user’s Strava data. With GPT-3, the approach is quite different.

The prompt (GPT-3 input) is comprised of the following:

- A brief summary that tells GPT-3 what you want it to do

- A number of examples, in this case it is the facts, and sample narratives

- The facts for the current Strava user

Given the above, GPT-3 will generate a narrative based on the facts given in (3).

Here’s part of the prompt for the passage of text that describes the user’s running patterns:

Write a narrative that describes when an athlete tends to go running, make it fun

and inspiring.

name: Colin

gender: M

long runs: Thursday or Monday

workouts: Sunday or Monday

time of day: morning

mostly runs on: weekday

narrative: We are creatures of habit, runners more so than most! You're most likely

to find Colin pulling on his trainers and hitting the road (or trail) on a weekday.

Colin is a morning runner, heading out as the sun starts to rise and when the roads

are nice and quiet. We've analysed the data, and he tends to go for long runs on a

Thursday or a Monday and works out on a Sunday or a Monday.

name: Julie

gender: F

long runs: Monday

workouts: Monday or Thursday

time of day: morning

mostly runs on: weekday

narrative: Runners tend to live their life on a loop. You're most likely to find

Julie pulling leaving the house and hitting the road on a weekday. Taking a closer

look, she tends to go for long runs on a Monday and works out on a Monday or a

Thursday. Also, Julie is a morning runner, heading out when the day has just begun,

giving her that satisfied feeling of starting the day right.

[... more examples omitted ...]

name: {{name}}

gender: {{gender}}

long runs: {{longRunDay}}

workouts: {{workoutDay}}

time of day: {{timeOfDay}}

mostly runs on: {{mostlyRunsOn}}

narrative:

(the real prompts I’m using contain around 10 example narratives)

The app replaces the tokens, e.g. {{gender}}, sends this prompt to the GPT-3 API, which then returns the narrative.

The end result is really quite impressive. Firstly, I can throw away all the code I previously used to try and create variability in the narrative (which I was never that happy with), and secondly, the narratives generated by GPT-3 are really quite creative - here’s an example:

Let’s see what Jack’s weekly training schedule looks like. We can see that he’s a late afternoon runner, often enjoying the last of the days sun. It looks like he tends to go for long runs on a Sunday, and work out on a Tuesday or a Thursday. He’s a man of routine, and we bet he’ll continue his routine to achieve his goals.

GPT-3 creates narrative, using linguistic tools such as analogies and metaphors, that I’d not thought of before, and as a result the Running Report Card really does feel bespoke. Finally 😀

If you’re interested, why not give it a try?

A few lessons learnt about prompt design

Working with GPT-3 has been a really interesting experience, and quite unlike any other interface or programming style I’ve encountered before. There is much talk in the GPT-3 forums about ‘prompt design’, or in other words, the challenge of describing the task you want GPT-3 to perform.

There is much that can be said about this topic, but for now, I’ll just share a few things I learnt along the way.

1. Refining prompts takes a lot of iterations

The output of GPT-3 is random in nature, resulting in variability in the text that it generates. Whilst ths is great for the purposes of my application, the narratives are bespoke and quite unique, it does make it hard to refine the prompt text. An improved narrative (based on my qualitative assessment) may be as a result of a better prompt, or could just be chance! I’ve yet to find a solution to this problem, beyond basic statistical methods - create lots of narratives and manually score them!

2. GPT-3 understand gender and pronouns

GPT-3 is able to infer gender from names, e.g. it infers that someone named ‘Alice’ is female. However, these inferences shouldn’t be relied upon. Names like ‘Sam’ are not assumed to be gender specific, and assuming gender from name alone is not to be encouraged. This is why one of the ‘facts’ I supply is the gender of the Strava athlete as provided by the API.

My earlier report card, using simple templating, had to handle pronouns (she) and possessive pronouns (her). With GPT-3 it understand these concepts already, as long as it knows the gender, the sentence is constructed correctly. This removes yet more logic from my application.

Better still, in the previous version, I never got round to handling the case where the Strava athlete had declined to specify their gender. With GPT-3 this is simple. I have one example with an ‘unknown’ gender, using they / their as pronouns, and that’s all it needs to handle the case effectively.

3. GPT-3 is less good at deriving facts

In the running report card I use various comparisons to help people better understand distances, time, height etc - for example, comparing their total elevation gain to the height of various mountains or landmarks. GPT-3 is quick to learn that the narratives should include these comparisons, but often gets the maths wrong:

During these runs he has climbed 62,599 feet, that’s the equivalent of climbing Mount Everest six times (but a bit less steep)

Everest is ~29,000 feet, so this runner has climbed Everest roughly twice.

The inability of large language models to perform even quite basic maths is well know. For this application, the solution is quite simple, create suitable comparison, and supply them as ‘facts’.

4. Creative and variable prompts work best

I found that the more creative and variable the prompts were, the better the end result. I’m effectively teaching GPT-3 to ‘mix it up’ a bit and that it doesn’t have to stick to a rigid format. I played around with different sentence structures and additional snippets of text, for example:

Most of his runs are on the weekdays, at midday, perhaps a sneaky lunch-break runner? Back to work full of adrenaline

Adam is a weekend runner, a time for leisure and exercise. You’ll most often find him heading out and building up a sweat at midday.

Jerry likes to keep his running on schedule, you’re most likely to find him working up a sweat on a Thursday. Jerry is an evening runner, heading out as the sun starts to set.

All three convey the same key facts about their running patterns, but the sentence structures, and additional commentary is very different.

5. Handling ‘excessive’ creativity

One of the most challenging problems I found was trying to encourage GPT-3 to employ the right level of creativity to the narratives. The API provides a couple of techniques for tuning the randomness of the output - temperature and Top-P (as described in Chris’ blog post).

An increased temperature results in narratives that are overly embellished:

On the days Carl works out, he’ll start easy and build it up to a quicker pace as the morning goes on.

(I didn’t supply GPT-3 with any facts about pacing)

Trial and error pointed to a temperature of ~0.8 being an optimum. However, I also found that the longer the completion provided by GPT-3, the more likely it was to throw in these over-embellishments and suspicious ‘facts’.

To combat this, in each case I generated a small number of narratives, picking the one that is closest in length to the average narrative length in my prompts. I found this provided a great balance, allowing creativity in the generated narrative, but significantly reducing scope for over-embellishing.

Summary

To briefly wrap up, I have been deeply impressed with GPT-3. The ‘prompt design’ programming model is intriguing and a new skill that you have to learn. Within this application I was able to create much better narratives, that are bespoke, creative and interesting, and all with less code than my previous template-based approach.

If you’re a runner, why not have a go at generating your running report card? Or if not, feel free to take a look at my report.

Colin E.