Back in December 2021 the software development community buzzed over the “Log4Shell” vulnerability that enabled hackers to gain access using injected code being executed when logged. For many organisations this posed a crucial-millions-of-dollars-worth risk. In retrospect, the decision to depend on a popular library felt like the right choice until the point it wasn’t. It was unavoidable, unless one would decide not to use any third party software and even then it’s presumptuous to think you won’t have security vulnerabilities in your own code. I would like to offer an overview of criteria one should consider before deciding between do-it-yourself and adopting third-party, often free and open source, software.

When considering how to resolve a particular problem, the first question you should ask yourself is “Can you do it yourself?”. This question relates to the Complexity of the problem. Consider the extraordinary case where the library is-odd is being downloaded little less than half a million times per week and the only thing it does is return true whenever its input is a positive integer which doesn’t divide by 2. Installing the library will take more time than writing the code required to do this simple test.

If you’re absolutely certain you can’t do it, skip to the next question, but perhaps it is at least worth considering, if you can do it, one must ask “Should you do it yourself?”. There are quite a few aspects to consider here. Starting with Responsibility, should you commit to maintaining your own solution or will it be better to outsource to someone who can give more attention to keep it up-to-date. Next, one must consider Specificity and Flexibility - how generic can the solution be, and how likely is it to change. Affordability and the amount of resources and time that would be reasonable to set for it is also critical. And finally, does it need a particular extensive domain-knowledge that you don’t have at the moment and you’re not particularly interested in. For example, writing a Markdown parser requires quite extensive knowledge of all the Markdown features and quirks.

One more check to do before we go on to adopt a new dependency is copy-pastability or in a more euphemistic phrasing - can you get inspiration from an existing code (assuming no licensing conflicts) and crediting the original code for future-reference if anyone ever wonders how and why you came up with this solution. Sometimes, especially with small code, it’s better to copy-paste the solution from a reliable and trust-worthy source (that is ideally also up-to-date). It does involve taking ownership of it, but allows you to cherry-pick and customise it and more importantly - you know it won’t be changed and break your application. Consider the story of Azer Koçulu who broke the internet when he decided to unpublish 11 lines of code that added padding to a string. Yes, writing those 11 lines yourself might take some time, but no matter how smart they might have been, the losses when your service dies because the dependency failed?

Joel Spolsky wrote back in 2001 about the Not-Invented-Here Syndrome as Developers’ pet-peeve to reinvent the wheel. Particularly he recalls when the Excel development team wrote their own C compiler that ended up being far more efficient and powerful than the official C compiler. He concluded with the advice: If it’s a core business function — do it yourself, no matter what. For example, If you’re a pharmaceutical company, write software for drug research, but don’t write your own accounting package. In reality, defining the “core business function” isn’t so straightforward - if you’re a pharmaceutical company - focus on inventing drugs, and not on software development, unless you can’t find anything better than what you can do on your own, given the resources available. If you’re a game-developer, do you need to re-invent Unreal engine? Will it help you or hinder you from producing an amazing game?

At this point we know we’re not going to write the solution ourselves and it’s time to consider what dependency, or library can we adopt to help us solve the problem. It’s important to acknowledge that more often than not, your client, customer or end-user won’t care about it. They want the solution to work. And from their perspective we should consider a few aspects as well. The end-user expects the solution to be Performant, Usable and Customizable enough to match their requirements. In that sense, you’re not responsible for the code but you are accountable and in case of failure it will be your head on the spike, and not that of a random person from Nebraska who happened to thanklessly maintain the code since 2003.

Customizability is the ability to update the component’s output (whether its interface, output format or its visual look-and-feel) to be more consistent with the rest of the application without making changes in its internal code. The problem is that the more customizable the component is, the more robust it needs to be and unavoidably less performant.

Usability has a lot to do with accessibility and the learning-curve we’re going to ask our user-end to go through to be able to use the component. An example for usability could be keyboard-support to navigate an image-gallery, or even ARIA support that might be critical to our inclusive target audience.

Of course, it’s super critical that our end-user expects a secured solution. Security is quite extensive and complicated, no matter how you look at it. Many companies get the code they use (whether internal and third-parties) audited, and although it might be expensive, the risk can cost much more. A method less expensive than hiring someone to audit the code (or do it yourself) is trust the crowdsource and take only popular libraries, hoping that someone else would have checked them by now. Popularity can be measured by github stars or by number of downloads per week statistics that can be found in package managers. Yet, it’s still worth remembering that the log4Shell issue mentioned earlier happened in a very popular library and it still took a decade for the breach to be discovered.

Popularity can also give us indications for other important factors, such as Support. Whether it’s community-driven or an official documentation, support is necessary the bigger and more robust the project is. Being able to ask questions and get answers is invaluable; Having someone else ask the same question before you is priceless.

How often the library is being maintained is also important but that must be measured along-side with maturity: yes, we want to know that issues are being addressed as they appear, but we also want to know the issues addressed are not due to the system breaking down. Popularity is a good but not a definite indicator for quality. Knowing who the developer is (individual or a team) can also give a good sense whether the code is reliable or not.

Next, we should check if that piece of technology is going to affect the rest of the team. How will it affect their tasks? Does the library spill out of your domain of responsibility into someone else’s and will require them to respond differently because of that? Be sure you don’t leave the project with an unusable and inaccessible feature (bare in mind, that’s more likely to happen with in-house written code).

As we dive into the potential library candidate we also need to verify its compatibility with the rest of our code and how much additional work will be required to configure and tailor to make it fit within our code. We should also check its efficiency - size-wise, or even feature-wise - how much of the library do we actually need and are we paying for it in performance? Learnability and how difficult it is to pick it up is also very important - is there enough documentation and information to shorten the learning curve.

Any library we pick should be Reusable so we won’t need to have different alternatives within a single project. For example, having one simple grid and yet another grid that has filtering is a bit redundant if you can hide the filtering-feature and avoid the simple grid component to improve performance. And although less likely to happen, it’s still worth considering interchangeability and the ability to switch from one dependency to another. It’s not something you would like to do, but making a “napkin-plan” can give you a better picture of how painful it would be in case the library fails to provide what we need from it and you will be forced to switch to an alternative solution.

In most scenarios Licence won’t be an issue as they are standard and luckily there are people in the dev community who will pick up anything that smells funky. Consider the “React Controversy” that took place in 2017: Facebook licensed React with a special licence named “BSD + Patents” which claimed that whoever has a (patent-related) legal dispute with Facebook is not allowed to use React library. It may sound reasonable but it can also be interpreted as “If Facebook stole your code and you sue them, you’ll be forced to discontinue your React-based application”. That’s one massive risk no one should take. Following a widespread backlash, Facebook re-licensed React under MIT. As mentioned, standard licences aren’t usually something to be overly concerned about, but being vigilant for the non-standard ones can save you from frustrating situations.

While for most aspects it is enough to consider just the adopted dependency, for the aspects of both security and legality, it’s probably worth considering transitive dependencies. These are the third parties used by the adopted dependency and very frustratingly - can be quite a handful. Consider the story of a popular npm library named event-stream. After the original author decided to abandon it, the maintainer added a dependency to it - flatmap-stream. Among the 1795 sub-dependencies this new transitive dependency had, a malicious code was hidden trying to steal private keys of bitcoin wallets. If you think that 1795 dependencies are still manageable, then consider Gatsby.js which has 19,000 (!) dependencies. Transitive dependencies make it very difficult to check for any security or legal issue you might bring in. Unless your organisation outsources these checks, it would be smart to avoid such heavy-dependant libraries as much as possible.

Finally, Ethics also play a part in deciding who is an acceptable partner in our journey. If you had a say in the matter, would you still allow a human-right violating government agency to use your products? Consider the developer protests sparked by ICE Contract With GitHub. In a more recent event, a third-party started acting as malware in protest against the war in Ukraine, deleting users’ files and popping anti-war messages. As difficult as it may be to argue against the intention, the results were damaging to the greater open-source community’s credibility.

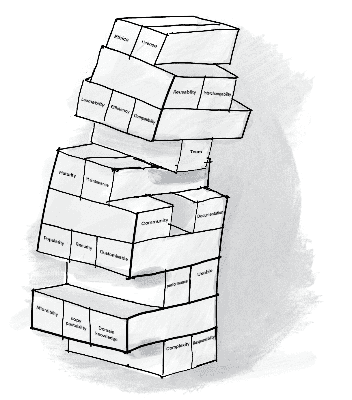

Indeed, there are a lot of aspects to consider before picking a dependency. On the positive side, most of the checks are either per-project (regardless of how many different alternative libraries can fit) or per-library (that can be considered for the next project) so it won’t be too surprising if we choose to stick with the library we already have. As mentioned earlier, at the bottom-line the important question to consider is “Will it help or hinder me from making an amazing product?”.