“Product development team cuts release process from 3 days to 2 hours!”

If I had to choose a headline I think that’s what it would be, although we improved in other areas as well. Our secret? We used Kanban.

Hang on - Kanban? Isn’t Kanban for those that just want to skip those boring Scrum meetings? Surely it’s for ad-hoc support work and not product development work? That’s what I’d heard previously, but I now know that not to be the case.

During this blog post I’ll introduce the situation we initially found ourselves in, give some background as to what Kanban is, then walk through some of the things we did.

Situation

Our client - a large investment bank - had a multitude of offerings and many ways for their customers to find out about them. Once a customer knew about something they wanted, e.g. a feed of relevant data, there would be a complex, lengthy process to obtain it. The client wanted a single one-stop-shop with an automated provisioning workflow to improve the customer experience.

They had formed a temporary team and produced an initial version of the product. We, being a team of 10, were then to come in and take over the development and progress it to live usage. We had relative freedom in terms of the development of the core software, but there were many integration points with other systems.

The client was using elements of Kanban for the initial development so that they could get going quickly, but there was an expectation to mature to Scrum. I personally hadn’t used Kanban before, but amongst the negative comments I had heard good things as well and was keen to see how far we could get with it before looking at a move to Scrum. There wasn’t an urgency to move to Scrum, there weren’t any issues that were being blamed on the Kanban usage, so it seemed like a good opportunity for experimentation. Both the client and the team were up for trying it!

What is Kanban?

The Kanban Method was devised by David J. Anderson. He was in Japan learning about lean manufacturing and thinking about whether there was some applicability to software development, whether it could help with busy software projects that always seemed to be stressful and late. The story goes that he was there during cherry-blossom season and all the parks he’d visited were really full of people - that is apart from one. This one seemed to have just the right number of people, there was space to breathe, contemplate and listen to the bees buzzing around the trees. The difference here was that at the entrance to the park there was someone with a limited set of physical tokens, on entry you’d be given one, on exit you’d give it back. This simple, visible mechanism meant that the number of people wouldn’t exceed a planned number. This simplicity was the inspiration for the Kanban Method.

The Kanban Method has three core practices:

Visualise

Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust on Unsplash

On a factory floor you can walk along the workflow, following the initial steps through to a completed physical product. If there is a problem at a particular stage in that workflow you can see it - physical items will start to pile up immediately ahead of it, and the downstream stages will be starved of work.

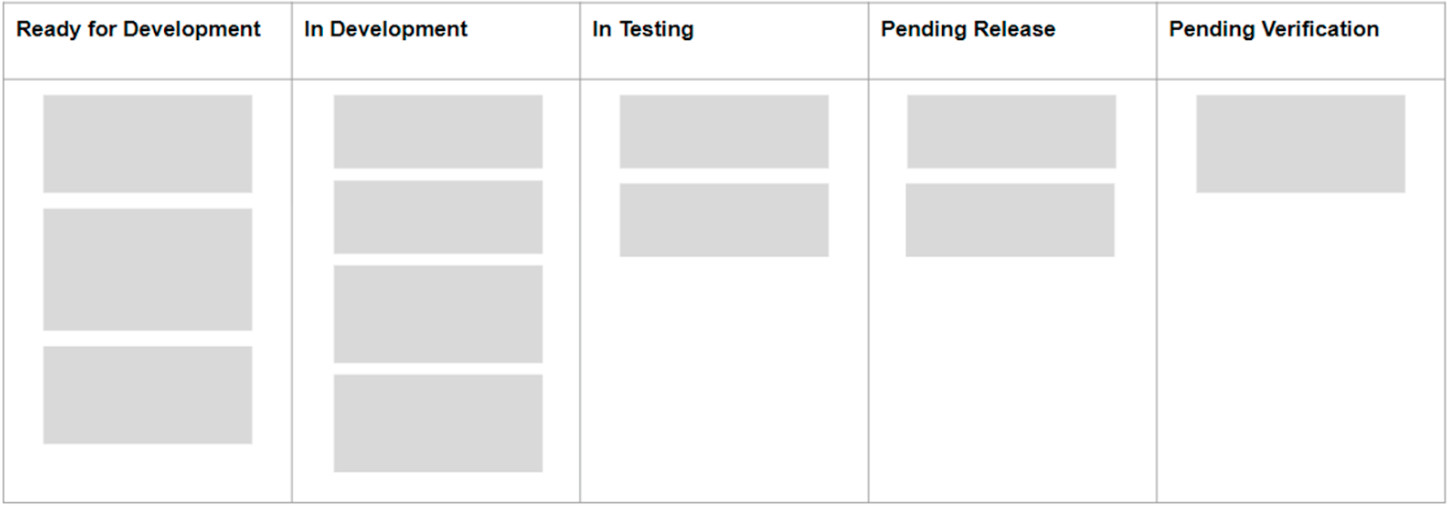

With knowledge work it’s much harder to see the problems. This is where the good-old Kanban board comes in. This aims to show us how our work works. I’d used these previously, but with the Kanban Method there is a greater emphasis on really getting your workflow represented on the board. In our case we weren’t so clear on the process to get to production, so we expanded our workflow so you could see at a glance what needed to happen next and where exactly the blockers were. We backed this up with explicit criteria that needed to be met before something could move onto the next stage.

Limit WIP (Work In Progress)

Thinking back to the park and the cherry blossom, Kanban is about limiting the amount of work that is going on at any one time. If we’ve got too much happening then invariably we’ll end up switching from one thing to another, and context switching is a real blow to productivity.

As per the method we put limits on a number of our workflow stages and over time wound these down. This helped us to focus on finishing things before starting new ones and to reduce the number of items in a release to production.

Manage flow

The last of the core three practices is all about getting valuable updates into the hands of the users as quickly as possible. The sooner we can do this then the sooner we can attack the biggest risks, and small, rapid updates means being able to change direction easily in response to what we learn. By focussing on the flow of work we’ll also be more aware of when there are problems that cause the production line to break.

One of the key things we did to improve flow was to run our daily meetings as a board-walk, rather than the traditional “What I did yesterday” etc. We’d start at the right hand side of the board and for each item talk about what needed to happen to progress it to the next stage. This really helped with focussing on finishing things as a team.

We also carefully tracked metrics, chiefly the Development Lead Time, i.e. for each item the time it takes from development work starting to it being available for use in production. This was particularly useful, as it meant that we’d be able to say to the client, for a new item of work, when it typically might be done, or by what date would we be 85% confident in having it done, based on prior performance. This was sufficient for higher-level scheduling, and avoided the need for upfront analysis and planning.

Supporting all of this was a pattern of regular meetings for governance, from regularly looking at the big picture and upcoming priorities, through refinement sessions to demos, reviews and retrospectives.

Mindset

I happened to have a trip to Japan arranged part way through the project, during which my wife and I learnt more about Japanese culture. At one train station there was a sign saying “Do not rush” which resonated with me. In a Japanese train station at rush hour there is a steady organised flow of people.

Photos by Tim Johnson

Reflecting after the trip, I came to see that the way we approached our work as team - with what are stereotypically Japanese strengths – was a key contributor to the success of our project: the strengths of focus, immersion, concentration, discipline, attention to detail, organisation, excellence, and slow determination - taking the time to do things well.

Outcomes

After 18 months:

- The success of the product prompted other areas of the client’s business to request their own versions

- The production release process was reduced from 3 days to 2 hours

- The record for resolving a production issue was 6 hours

- A neighbouring team switched to Kanban after seeing our processes in action

Conclusion

I’m grateful to have been in a position to fully explore Kanban. I think the results have been amazing, having a relentless focus on efficiency really drove down the time to do production releases, and being able to resolve a production issue (properly) within 6 hours? That’s not something I’ve experienced before.

So no, Kanban isn’t the lazy option. And no, Kanban isn’t just for ad-hoc support work. I think that Kanban’s simple core practices together with the right mindset is the ultimate expression of agile.

If you’d like to know more then feel free to get in touch, I’d be happy to talk more about it! Reading wise I’d recommend Kanban in Action by Marcus Hammarberg and Joakim Sunden. For training I’d recommend looking at the courses on offer at Kanban University.