Have you ever been frustrated by how little ChatGPT knows about you? How it doesn’t (yet!) involve you in its decision-making process? Or how it’s always so confident in its responses, even when they can be wildly inaccurate?

I don’t want to start off on the wrong foot; I think ChatGPT is amazing! It’s revolutionising our industry, from how we learn new technologies to how we interact with our data. New advances are emerging left, right, and centre. So what can we do to keep up with the tide? This is a question that a group of us, with no prior experience in AI but a shared desire to learn, set out to answer.

Our goal is to help our external stakeholder, Chris Booth, bring his vision to life: an ultra-personalised chatbot that can infer information to help solve questions more efficiently and accurately. You can see the current state of the project on github here.

When I asked ChatGPT for a film recommendation, I got a generic response:

The idea is that InferGPT wouldn’t be so confident in its response. Instead, it would know who it was talking to, what genres they like, and ideally, what they have watched recently. Armed with this knowledge, the conversation becomes a lot more engaging. Instead of producing what seems like a random list of films, we could infer information to give a more targeted response. Even better, we could ask the user for feedback to improve the chatbot’s confidence.

The Journey to Building InferGPT

When it came to building this chatbot, we had many options. We spent the first month or so upskilling and exploring the various technologies available. We became familiar with LangChain, a framework that helps build AI applications quickly. However, we wanted to learn and have more control, so we decided to use Python and steer away from LangChain.

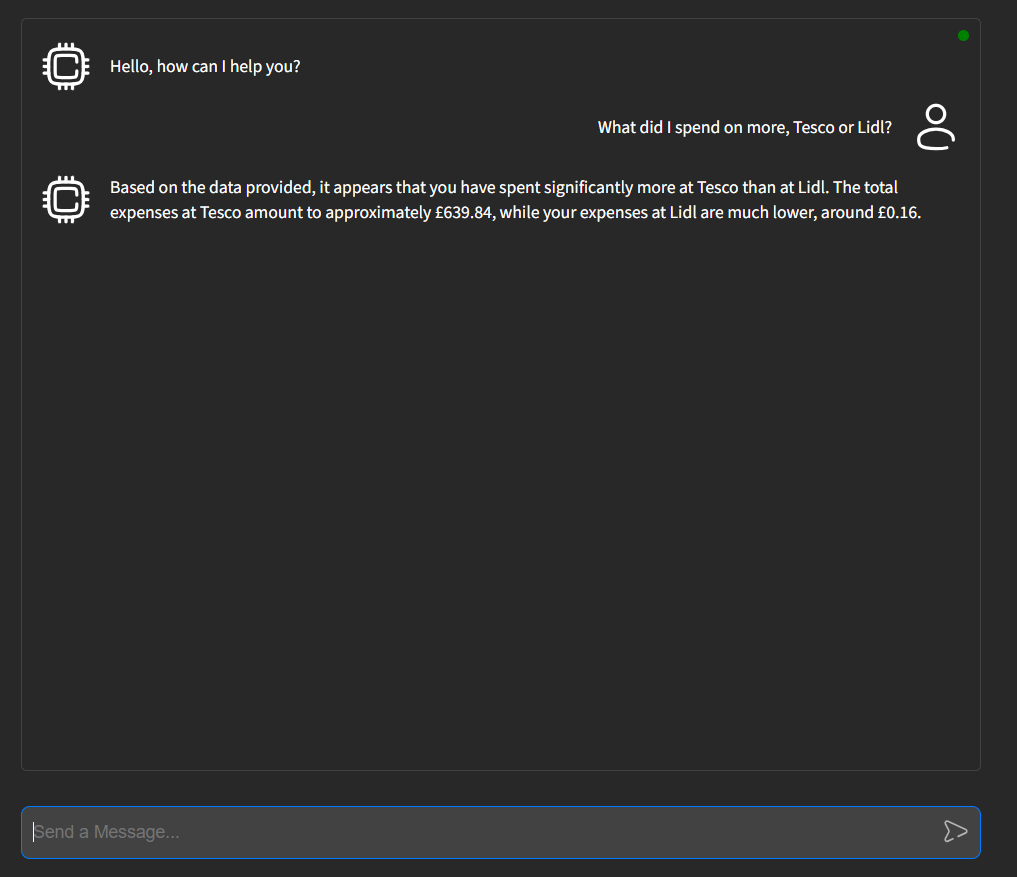

Because of our familiarity with it and to keep the project focused, we decided to implement a simple frontend application in React, a library the team was comfortable with. It would be used to make simple requests to our backend (a FastAPI) to get chat completions. Below is the simple UI that we made:

Designing the Backend

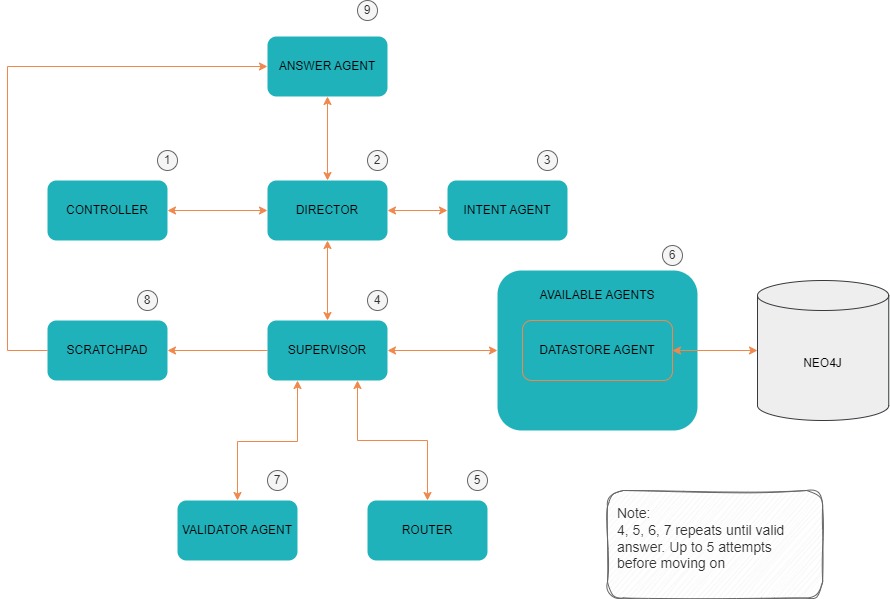

The main design focus was the backend. With Chris’s vision, we had a starting point: a multi-agent system that would break down a user’s query into its solvable tasks. What does “multi-agent” mean? Well, without LangChain, we had the freedom to define it ourselves. To us, an agent is an entity that has access to a large language model (LLM), a defined persona (the system prompt used with the LLM), and a list of tools. Tools are functions that the agent can invoke to solve a given task. So, a multi-agent system is a collection of agents that can solve their own domain-specific tasks, all stitched together.

We aimed to minimise the overuse of LLM models. Where possible, such as in the code connecting the individual agents, we used more traditional development strategies. Below is one of the first iterations of our backend system:

Key Flow

- Controller: The entry point to the backend, where we set up our chat endpoint via FastAPI. The chat endpoint delegates to the director to get the response for the user.

- Director: No LLM involved. The director handles the user’s query, breaking it down into solvable questions for the supervisor and returning the final response to the controller.

- Intent Agent: An LLM call is used to break up the user’s original query into its intent, ensuring more reliable and repeatable results.

- Supervisor: No LLM involved here. The supervisor loops through the questions it needs to solve:

- Router: Decides the best next step. With a list of available agents, the current task to solve, and the history of results, the router makes an LLM call to decide which agent should solve the task.

- Available Agents: The supervisor invokes the chosen agent to get a response. For example, a datastore agent would be chosen for a data-driven question. It would then use an LLM to generate a Cypher query to retrieve the data and return the response to the supervisor.

- Validator Agent: With a response from the question agent, the supervisor checks with the validator agent if the answer is sufficient. An LLM call is used to determine whether the answer is satisfactory.

- Scratchpad: A simple object that the supervisor uses to record every answer to each question.

- Answer Agent: With each result written to the scratchpad, the director can then invoke the answer agent to summarise the scratchpad, resulting in the final response for the user.

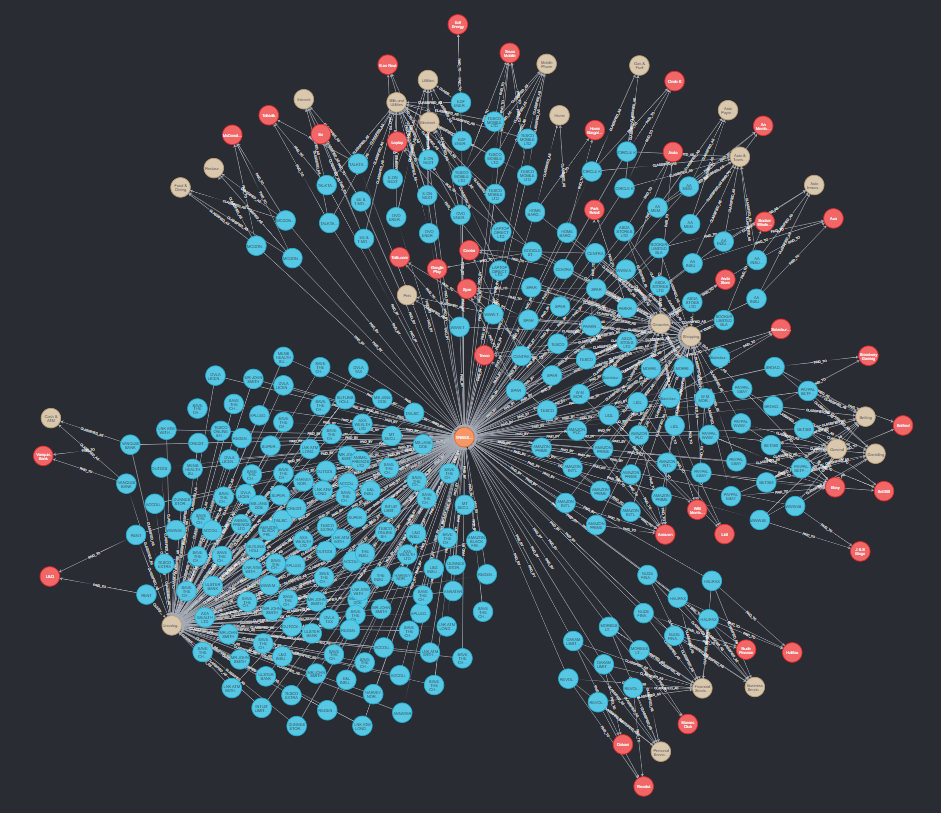

We chose a neo4j database over traditional SQL. Here, the relationships between entities are treated as first class citizens. This means that traversing the graph and making “connections” between data points is a lot more efficient and intuitive. We would leverage this to answer user specific questions, and in the future, perhaps infer details by traversing the graph fewer times than necessary.

Handling Failures

The supervisor loops through the questions it needs to solve, implementing retry logic into the flow. If the router picks an agent to solve the task but fails at the validation stage, we try again. The unpredictable nature of LLMs means that we could get a different answer the next time around.

Testing

To test this design, we produced some dummy user data. We injected a lot of monetary transactions into the neo4j database. Doing this created a complex graph of interconnected nodes. Reading the graph by eye would prove very difficult to extract useful information. A snapshot of (some!) of the test data:

Say we wanted to sum up the total spending to a single merchant. This is where the datastore agent would come in, one of our question agents. It is capable of generating cypher queries (the querying language for neo4j) from natural language, based on a schema that it has on the graph. Now, we’d be able to ask these sorts of questions, make comparisons between companies and spending, all without knowing how to write a single query ourselves. Below is an example result of such a question:

This is great; we have a way to ask natural language questions on a complex data source. But how does this fit in with the grand vision? How will you infer information to make better decisions? The answer is that this is only the first, small step towards the bigger goal. We have shown that it is possible to build a multi-agent chatbot, from scratch, to answer data-driven questions.

Future

There are many more steps to go. Getting the user in the conversation is an exciting area, for example. By asking the user for clarification, we could eliminate unnecessary calls to language models to interpret meaning. Not only this though, but the user could be used for validation. Getting them to confirm the meaning, or a result, could prove valuable.

On the other hand, the area of creating agents is interesting. Manually expanding the available agents would increase the capabilities of the chatbot. But allowing the chatbot itself to create its own agents would vastly improve its abilities. The inspiration for this comes from a recent whitepaper where a team built a bot that could play Minecraft by building its own set of skills.

Sustainability in software is a big topic too. We’re developing this multi agent system, but what impact does it have on the environment? More monitoring would need to be put in place to help answer this question.

I hope I’ve given you a flavour of what is going on with InferGPT, and that It is possible to build a full stack application that involves an LLM from scratch. InferGPT is (at the time of writing!) an ongoing project, so watch this space.