Markitecture or Reality? Separating Substance from Hype

In an industry notorious for rebranding existing technologies with shiny new names, the “Data Lakehouse” faces immediate skepticism. Is this another case of markitecture—marketing masquerading as architecture—or does it represent genuine technical progress?

The answer, like many things in data engineering, is nuanced. While “Lakehouse” is undeniably a Databricks-coined marketing term, it describes real technological capabilities that address longstanding problems neither warehouses nor lakes solved adequately. The question isn’t whether the term is marketing (it is), but whether the underlying architecture delivers on its promises.

From Warehouses to Lakes: An Unbalanced Compromise

Data warehouses dominated enterprise analytics for good reason. They offered high-performance, structured environments optimized for SQL queries and reporting, with the reliability guarantees that enterprises demanded—ACID transactions, robust governance, and predictable query performance. In a world of relational data, they provided the specialised capabilities that enabled complex OLAP queries over large volumes of historical data.

But as “big data” exploded and non-relational data became ubiquitous, traditional warehouses revealed their brittleness. High costs from specialized software and hardware, complex integration requirements, and inflexible schema-on-write approaches made them increasingly unsuitable for diverse, rapidly evolving datasets.

When James Dixon coined “data lake” in 2010, he was responding to Hadoop’s promise of cheap, scalable storage. The aquatic metaphor was apt—and like real lakes, data lakes proved susceptible to pollution. What Dixon didn’t anticipate was how quickly his pristine lake would become the notorious “data swamp”.

Data lakes brought unprecedented flexibility and cost savings through commodity hardware and open-source software. Their schema-on-read approach allowed raw data ingestion with transformation deferred until needed—a godsend for data scientists working with varied datasets and CTOs wanting lower capex and faster delivery.

Yet this flexibility came at a steep price: lack of ACID properties, weak governance, persistent data quality issues, and poor query performance. The promise of turning raw data into insights often foundered on the reality of poorly organized and inconsistent lake storage.

The Lakehouse: Marketing Term or Architectural Evolution?

Popularized by Databricks, “Lakehouse” is admittedly a marketing term that rebrands a collection of existing technologies under a compelling metaphor. But sometimes marketing terms capture real architectural shifts, and the Lakehouse addresses genuine pain points that neither warehouses nor lakes solved adequately.

Databricks defines the Lakehouse as an architecture supporting high-volume structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data in a single platform—with transactional integrity, schema evolution, and performance optimization built in. More precisely, Schneider et al. describe it as “an integrated data platform that leverages the same storage type and data format for reporting and OLAP, data mining and machine learning as well as streaming workloads.”

A key insight here is unification: instead of maintaining separate systems for different workloads, the Lakehouse provides a single platform spanning the full analytics spectrum. While a data lake is simply distributed storage, the Lakehouse adds critical layers for metadata management, transaction control, and query optimization.

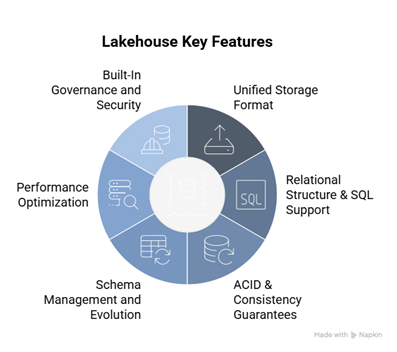

Key Features: The Technical Reality

There are several key features that enable the Lakehouse to achieve this:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Unified Storage Format | Lakehouses standardise on columnar formats like Apache Parquet, enabling efficient storage and query performance across diverse workloads. This isn’t just about convenience—it eliminates the operational overhead and data movement costs of maintaining separate systems for different use cases. |

| Relational Structure & SQL Support | Columnar storage allows collections to be defined with relational structure and queried using SQL, including for semi-structured formats like JSON. This democratizes data access by leveraging existing SQL skills rather than requiring specialized programming knowledge. |

| ACID & Consistency Guarantees | This is where Lakehouses fundamentally differentiate from traditional data lakes. Frameworks like Delta Lake and Apache Iceberg bring ACID semantics to distributed storage, ensuring reliable and consistent reads and writes even in concurrent environments—solving the “eventual consistency” problems that plagued early lake implementations. |

| Schema Management and Evolution | Unlike raw data lakes, Lakehouses support both schema enforcement (preventing bad data from corrupting datasets) and schema evolution (allowing structures to change without breaking downstream systems). This balance between flexibility and reliability is crucial for production environments. |

| Performance Optimisation | Through columnar storage, data skipping, Z-ordering, and sophisticated indexing, Lakehouses deliver query performance that approaches warehouse levels while maintaining lake-scale economics. These optimizations require deep integration with the storage engine—you can’t just bolt them onto existing systems. |

| Built-In Governance and Security | Fine-grained access control, comprehensive audit logging, and automated data lineage tracking are increasingly standard in Lakehouse implementations—critical capabilities for meeting regulatory requirements and enterprise governance standards. |

Open Table Formats: The Real Innovation

Open table formats represent the most significant technical innovation enabling Lakehouse architectures. These formats define how data files, metadata, schemas, and transactions are structured and managed — standardizing access patterns and supporting key features like ACID guarantees, schema evolution, and time travel. Open formats sit on top of columnar file types like Apache Parquet, providing excellent read performance while layering sophisticated schema management and transaction control on top.

There are multiple different Open Table formats currently in use:

| Feature | Delta Lake | Apache Iceberg | Apache Hudi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Databricks (Spark-focused) | Netflix (broad ecosystem) | Uber (streaming-optimized) |

| Key Strength | Deep Spark integration | Advanced partitioning & branching | Real-time upserts & CDC |

| ACID Support | Full ACID | Snapshot isolation | Optimistic concurrency |

| Ecosystem | Databricks-centric | Vendor-neutral | Real-time analytics focused |

Delta Lake excels in Spark environments with robust schema enforcement, time travel capabilities, and scalable metadata handling. It’s the default in Databricks but, as an open-source library, it is increasingly supported in other engines.

Apache Iceberg offers the most sophisticated approach to partitioning with hidden partitioning and full schema evolution. Its git-like branching and tagging capabilities are genuinely innovative. AWS’s recent S3 Tables launch signals strong enterprise backing.

Apache Hudi focuses on incremental processing with efficient upserts, deletes, and change data capture integration—crucial for real-time analytics workloads.

The 2024 acquisition of Tabular (founded by Iceberg’s original authors) by Databricks signals an interesting shift toward format convergence, though vendor preferences will likely persist.

Real-World Implementation: The Medallion Pattern

Low-cost storage enabled organizations to maintain multiple dataset versions, supporting different consumer needs and incremental transformations.

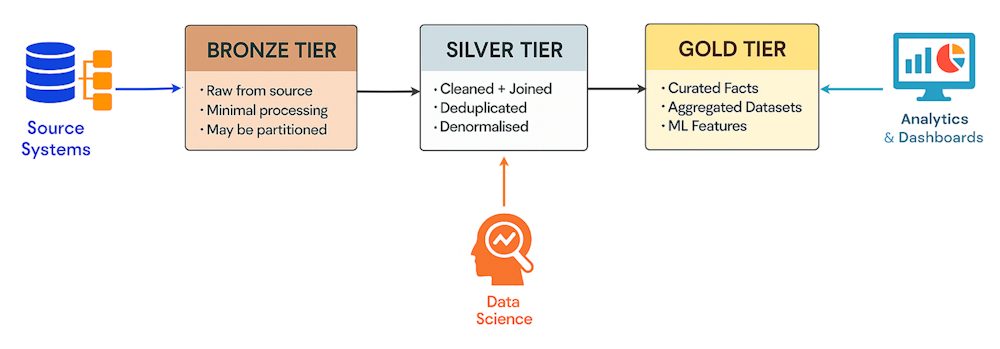

This has led to the Medallion Architecture becoming nearly ubiquitous in Lakehouse implementations. Here data is typically organised into Bronze (raw), Silver (cleansed), and Gold (analytics-ready) tiers (though custom tiers are common).

While purists correctly note that Medallion isn’t truly an “architecture,” this layered approach provides a practical pattern for managing data lifecycle and quality across complex pipelines. It accommodates both exploratory data science work (primarily Silver tier) and production BI reporting (Gold tier), while maintaining full data lineage from source to insight.

Platform Reality Check

Major platforms have embraced the Lakehouse model, but their implementations reveal the gap between marketing and technical reality:

Databricks naturally provides the most cohesive Lakehouse experience, with Delta Lake deeply integrated into the Databricks Runtime. However, this tight coupling can create vendor lock-in concerns, e.g. with Delta Live Tables, for organizations wanting format flexibility.

Microsoft Fabric positions itself as a unified platform with “One Lake” storage and Delta Lake as the default format. Yet Fabric’s implementation still requires format conversion for specialized workloads—KQL time series data uses a custom format that’s subsequently mirrored into Delta with inevitable latency, undermining the “one format” promise.

Snowflake supports external Iceberg tables while maintaining its proprietary format for core operations. Their Unistore capability adds low-latency transactional support on top of the original warehouse storage format—a practical compromise that acknowledges format limitations.

AWS and Google Cloud provide Lakehouse capabilities through services like Athena, BigQuery, and S3 Tables, but these implementations often feel like retrofitted solutions rather than ground-up architectures.

The reality is that most organizations still operate multiple storage systems despite Lakehouse promises of unification. The formats excel in their sweet spots but haven’t eliminated the need for specialized systems entirely.

What Problems Actually Get Solved

Lakehouses address several longstanding architectural pain points, though not always as completely as advertised:

- Consistency: ACID transactions ensure data integrity, eliminating the consistency issues that present real challenges in data lakes. This is perhaps the Lakehouse’s most significant achievement—making distributed tables reliable enough for production analytics.

- Governance: Built-in access control and lineage tracking support enterprise-grade governance requirements. However, implementing comprehensive governance still requires significant organizational discipline and tooling beyond the storage layer.

- Performance: Columnar formats and query optimization deliver substantially faster insights at scale than traditional data lakes, though rarely matching specialized warehouse performance for complex analytical queries.

- Flexibility: Schema evolution allows teams to iterate without costly rework, enabling more agile data modelling approaches. This flexibility proves crucial as data science workflows become more experimental and iterative.

The Limitations Nobody Discusses

Despite the compelling value proposition, Lakehouses introduce their own complexities that organizations must navigate:

- Operational Complexity: Managing multiple table formats, optimizing partition strategies, managing consistent backups and coordinating schema evolution across teams requires sophisticated operational capabilities that many organizations don’t expect.

- Skills Gap: While SQL support democratizes access, optimizing Lakehouse performance requires deep understanding of columnar storage, partitioning strategies, and distributed computing—skills that remain scarce.

- Migration Challenges: Moving from existing warehouse or lake architectures to Lakehouse patterns involves significant data migration, pipeline rework, and organizational change management that vendors rarely adequately address.

- Cost Reality: While storage costs decrease, compute costs for processing large datasets can exceed traditional warehouse expenses, particularly for organizations with inefficient query patterns.

The Future of Lakehouse Architecture

Looking ahead, several trends will shape Lakehouse evolution:

- Format Consolidation: The current three-way split between Delta, Iceberg, and Hudi is likely unsustainable. Iceberg’s vendor-neutral positioning and AWS backing give it advantages, but Delta’s Spark integration and Databricks ecosystem remain formidable. Expect market forces to drive toward one or two dominant formats.

- AI/ML Integration: Machine Learning & AI workloads increasingly drive Lakehouse adoption, as these systems need the same flexible, scalable storage that powers analytics. The ability to train models directly on analytical datasets without data movement represents a compelling value proposition. As in so many domains, GenAI promises to transform data engineering as complex analysis and transformation work is delegated to AI agents.

- Real-Time Convergence: The boundary between batch and streaming processing continues to blur; though technical capabilities to support reliable streaming of data from Bronze throught to Gold tiers need to be better integrated. Lakehouses that can efficiently handle both analytical queries and real-time updates will have significant advantages as organizations demand more immediate insights.

- Governance Automation: As regulatory demands increase, expect more sophisticated automated governance capabilities built into Lakehouse platforms—moving beyond basic access control to automated data classification, retention management, and compliance reporting.

Conclusion

The Data Lakehouse represents evolutionary progress in data architecture—not revolutionary change, but meaningful improvement over existing approaches. It succeeds by acknowledging that perfect solutions don’t exist and instead offers workable compromises that balance flexibility with reliability, cost with performance, and innovation with governance.

The real test isn’t whether “Lakehouse” survives as a term (marketing terms rarely do), but whether the underlying architectural patterns prove sustainable. For organizations navigating increasingly complex data environments, the Lakehouse approach offers a more pragmatic path than the extremes of pure warehouse or pure lake architectures.

As open standards mature and platform support expands, expect these architectural patterns to become standard practice, regardless of what we call them. The substance behind the marketing is real—and that’s what ultimately matters for practitioners building data systems that need to work in the real world.