Architecture decisions don’t usually fail fast or in a dramatic fashion. They fail quietly, long after the decision was made. That’s usually because stakeholders weren’t aligned on what success meant, constraints stayed implicit, trade-offs were never made explicit, and no one clearly owned the decision once delivery began.

Options appraisal is one of the simplest ways I know to reduce those failure modes. It provides a structured approach to exploring alternatives, weighing trade-offs, and landing a recommendation that stakeholders can scrutinise.

It won’t magically make decisions easy, but it does make them clearer, more collaborative, and much harder to undo for the wrong reasons.

When people talk about options appraisal, they often mean technology selection. In practice, that’s just one specialised case, and it usually comes with additional considerations. I use the same underlying technique in work where it’s more about strategy and direction rather than selecting a tech stack, which is the focus here.

Is an options appraisal always worth it?

I don’t reach for options appraisal by default. I reach for options appraisal when:

- the decision is hard to reverse (or expensive to change later)

- it cuts across different stakeholder groups, each with their own priorities

- success is multi-dimensional (cost AND speed AND risk AND operability…)

- I can already see future-me asking “why did we choose this again?”

If it’s a low-risk choice or you’re still exploring, a quick spike, proof of concept, or desk-based research is often enough.

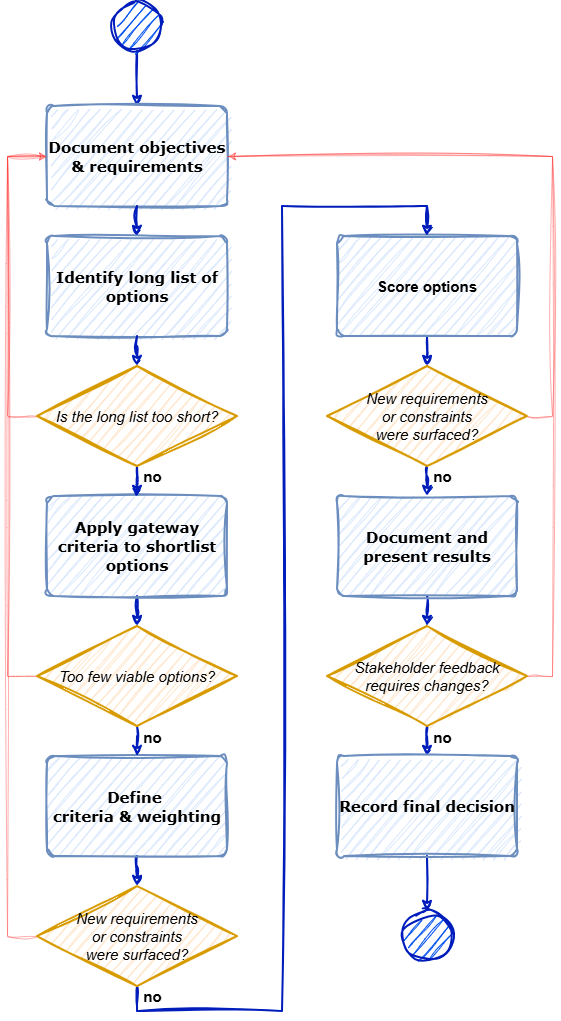

The process (and the important bit: the loops)

In theory, options appraisal is a sequence. In practice, though, it’s a loop.

Exploring options tends to surface new requirements, constraints, or stakeholder feedback, which in turn makes you revisit earlier assumptions and refine the problem you’re trying to solve.

Let’s briefly go through each stage, focusing on what you’re trying to achieve and a few practical checks that help avoid common traps.

1) Objectives and requirements: align first

What you’re trying to achieve: a shared understanding of what success looks like and the real constraints.

This is where you would list out:

- the functional requirements: what the solution must achieve, and

- the non-functional requirements: the constraints that matter, such as operability, compliance, maintainability, security, accessibility, and cost.

Requirements are where hidden assumptions like to hide, particularly when different stakeholders think they’re aligned but aren’t.

That’s why this step is about building a shared understanding, not producing a perfect specification. Treat the result as a snapshot, not a contract - it will quite likely evolve.

Some considerations:

- Do you have sufficient diversity of stakeholders, and have they been engaged early enough?

- Have you captured what success looks like from their different perspectives?

- Do all stakeholders share a common understanding of the objectives and what is explicitly out of scope?

- Have you identified key organisational constraints, such as delivery timelines, budget, and team capabilities?

- Do you understand the current architectural principles that are expected to guide this decision?

- Are you aware of previous organisational decisions relevant to this topic?

2) Long list: maximise learning, not consensus

What you’re trying to achieve: a set of meaningfully different approaches.

If your options are all variants of the same design, the appraisal will produce a confident-looking answer to the wrong question.

I try to keep the long list broad (often no more than ~10 options), and I explicitly delay judgement. Weak options are still useful: they often expose trade-offs you didn’t know mattered.

At this stage, the output can be very lightweight: a simple list or table with a short description of each option and why it’s meaningfully different is usually enough.

Some considerations:

- Are you prematurely dismissing options without justification?

- When options are rejected, are the reasons recorded transparently?

- Have any assumptions or constraints been tightened too early, limiting the option space?

- Have you looked beyond familiar patterns, past projects, or the immediate team to broaden the set of options?

3) Shortlist: gateway criteria and the “do nothing” baseline

What you’re trying to achieve: a shortlist of viable candidates worth scoring properly.

Gateway criteria are the must-haves every viable option must meet - often a small subset of the non-negotiable requirements identified earlier (hard deadlines, legal obligations, essential service needs). They’re the constraints you’re not prepared to trade away, also known as, the “if it fails this, it’s not an option” rules.

Aim to reduce to 3-5 options, and always include “do nothing”. It’s not there to win; it’s there to expose the cost of change.

If the gateway criteria eliminate everything, that’s usually a signal that:

- a constraint was assumed to be hard when it isn’t, or

- the problem statement needs rework.

And that’s very ok, it’s now time to loop back.

Some considerations:

- Are the gateway criteria genuinely non-negotiable, rather than strong preferences?

- Have you reviewed and agreed the shortlist with the stakeholders?

- Does the shortlist still represent a meaningful range of approaches and trade-offs, across commercial, organisational, operational, and technical dimensions?

- Have you explicitly included the “Do Nothing” option?

4) Criteria and weightings: force the priority conversation

What you’re trying to achieve: a scoring framework that reflects stakeholder priorities.

Criteria should be derived from requirements and constraints. Weightings are where those priorities stop being implicit and have to be agreed.

This step is probably less about the numbers than the discussion it triggers. In my experience, agreeing weightings is where stakeholders are forced to be explicit about what they care about most, where they’re willing to compromise, and where they aren’t.

The same team can land on two perfectly reasonable decisions from the same option set, depending on what matters most at the time. If time to deliver is the priority, a short-term workaround can look tempting. If security or operability takes precedence, that same option start to feel like the wrong trade-off.

In practice, I usually capture this as a simple table or list of criteria with relative weightings, plus a short note on why each one matters in this particular context.

If you’re struggling to agree weightings, that’s not a process failure. It’s the process doing its job: forcing the trade-off conversation early.

Some considerations:

- Are your criteria clearly derived from the previously agreed objectives and requirements?

- Do the criteria cover both short-term delivery concerns and longer-term considerations such as operability, security, and total cost of ownership?

- Have the criteria and weightings been reviewed and agreed with stakeholders?

5) Scoring: evidence, notes, and healthy challenge

What you’re trying to achieve: a reasoned comparison, not an illusion of objectivity.

I like simple scales (e.g. 0–5), but the most valuable artefact isn’t the number — it’s the note beside it.

Evidence can come from desk research, conversations with specialists, small prototypes, and operational “what would break at 3am?” reviews. For bigger decisions, it can be worth running a proof of concept, even if it’s time-boxed and imperfect.

I also strongly prefer group scoring with a small set of stakeholders. In practice, it reduces bias and builds shared ownership far better than scoring in isolation.

Some considerations:

- Are you involving the right stakeholders in scoring and weighting discussions?

- Are scores grounded in evidence (research, prototypes, operational experience) rather than opinion?

- Are unusually high or low scores being challenged, discussed, and documented?

A simple scoring example

Scoring approach:

Each criterion is scored from 0 (poor) to 5 (excellent) and multiplied by its weighting.

| Option | Time to deliver (×3) | Security (×5) | Operability (×2) | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 → 15 | 1 → 5 | 4 → 8 | 28 | Known and operable, but weakest security posture |

| Option A | 3 → 9 | 3 → 15 | 4 → 8 | 32 | Balanced improvement with manageable operational cost |

| Option B | 1 → 3 | 5 → 25 | 1 → 2 | 30 | Pushes security to the maximum, but is the hardest option to live with day to day |

If the table feels uncomfortable, that’s a feature: it makes disagreements visible while you still have time to do something about them.

6) Presenting results: tell the story, not just the score

What you’re trying to achieve: a decision-ready narrative that shouldn’t surprise anyone in the room.

By the time I present the results, the decision itself should already feel familiar to everyone. I’m not trying to persuade people with numbers at this point — I’m simply reflecting the discussions we’ve already had.

At this point, the presentation is usually a formality — a chance to bring everyone together and make the decision explicit. Most of the hard work should already have happened earlier. If it doesn’t feel that way, that’s a signal to loop back and do more of that work.

Stakeholders should now all be able to answer the same basic questions:

- What options did we consider, and which ones did we rule out (and why)?

- What mattered most in our context?

- Where are the real trade-offs and risks?

- What are we choosing not to optimise for?

My role here isn’t to make the decision for the group. Sometimes I’ll make a recommendation, grounded in the agreed criteria and evidence; sometimes I’ll deliberately stop short of a recommendation and focus on highlighting the implications of each option.

I’ll often include charts or totals as a summary, but I treat them as supporting material rather than the decision itself. Either way, the aim is to make the implications of each option hard to ignore.

If views are still split at this stage, that’s not a failure. In the past, I’ve explicitly asked stakeholders to make the call, sometimes even to vote, but only once the trade-offs are fully visible and understood. Even when people disagree on the outcome, they’re usually aligned on why it was chosen.

7) Record the decision: future-you will thank you

What you’re trying to achieve: a durable decision trail.

However you capture it, the outcome of an options appraisal needs to be recorded somewhere. In many teams, that takes the form of an Architecture Decision Record (ADR). In others, it might live in an existing governance document, design pack, or decision log.

In practice, I’ll usually work with the client’s existing ways of capturing decisions, rather than introducing something new. The specific format matters far less than the fact that the decision exists as a shared artefact that people can come back to.

What’s worth recording isn’t just the outcome, but the context around it: the options that were considered, the trade-offs that were accepted, and any assumptions or review points that shaped the choice.

It helps avoid the familiar “why are we doing this again?” conversation — usually at the exact moment when the original context has faded from memory.

Final thoughts

If you remember three things, I’d make them these:

- Separate generating options from judging them. You want range before you want consensus.

- Make weightings explicit. If stakeholders can’t agree what matters most, the decision isn’t ready.

- Write it down. Not to satisfy process but to protect delivery.

Options appraisal isn’t the only way to make decisions, but it’s a reliably good one when the stakes are high and the trade-offs are real.