“Do you like old computers?”

I watch as Ben, my plumber, hauls a large cardboard box marked with “AMSTRAD” in blue lettering down from my attic. After he fixes my extractor fan and leaves for his next job, I open up the box held together with staples and ancient, yellow tape, to find a full monitor, keyboard and printer set, complete with floppy disks:

It is an Amstrad PCW 8256. I have no idea what it can do or how it works, but I’m excited to find out. I power it on only to find a screen filled with green lines. I try pushing one of the floppy disks into the reader, but nothing happens.

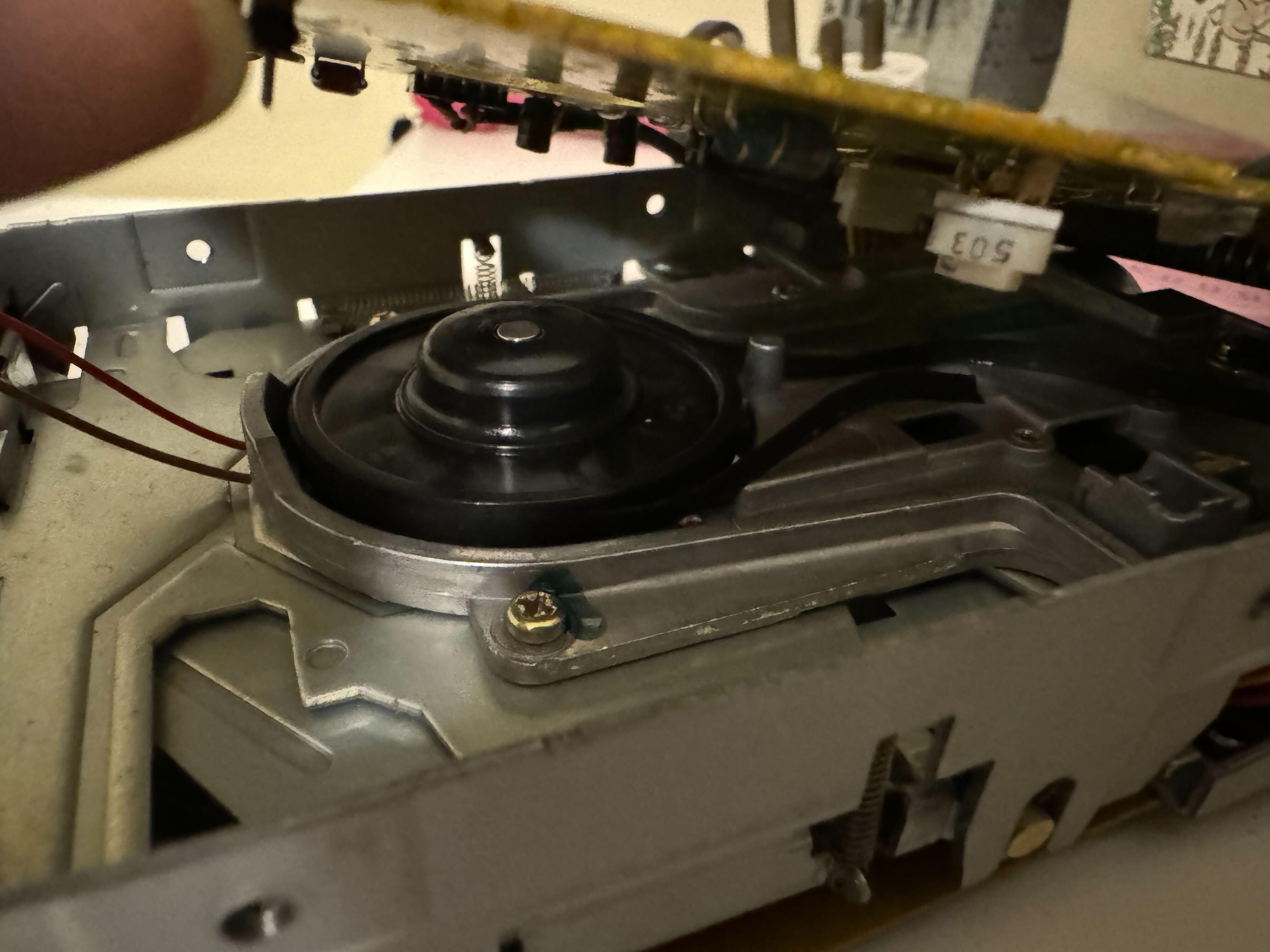

After some digging, I find that that blank screen meant the floppy disk was probably not being read, likely because the reader’s drive belt (which is essentially a rubber band) had perished. Sure enough, when I open up the monitor case and the disk reader inside, I see the drive belt is in bits:

Luckily, there are a few sellers on eBay who offer replacement drive belts in exactly the right size, so after the new one and some isopropyl alcohol arrives in the post, I clean off the two spools and replace the band (many thanks to Chips y Bits on YouTube who has a very straightforward demonstration of how to do this). The PCW was now able to read disks again!

The previous owner of this computer had left behind a few disks, one with Locoscript on it, which is the standard software that came with the PCW that is used to write and print documents. There wasn’t much on there – mainly just an article about train station architecture, and interestingly, a wedding speech. The other disk of interest was the one with the BASIC interpreter on it.

About the Amstrad PCW

The Amstrad PCW 8256 comes with a BASIC (short for Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) interpreter and Locoscript as standard software disks. Boasting some 256 KB of RAM (as its name suggests), it was considered a powerful microcomputer at the time of its release, and was a competent and affordable choice for computer buffs, gamers, and office users alike. It’s also still pretty popular with retro computer hobbyists today, with PCWs of varying function selling online for around £100-£200.

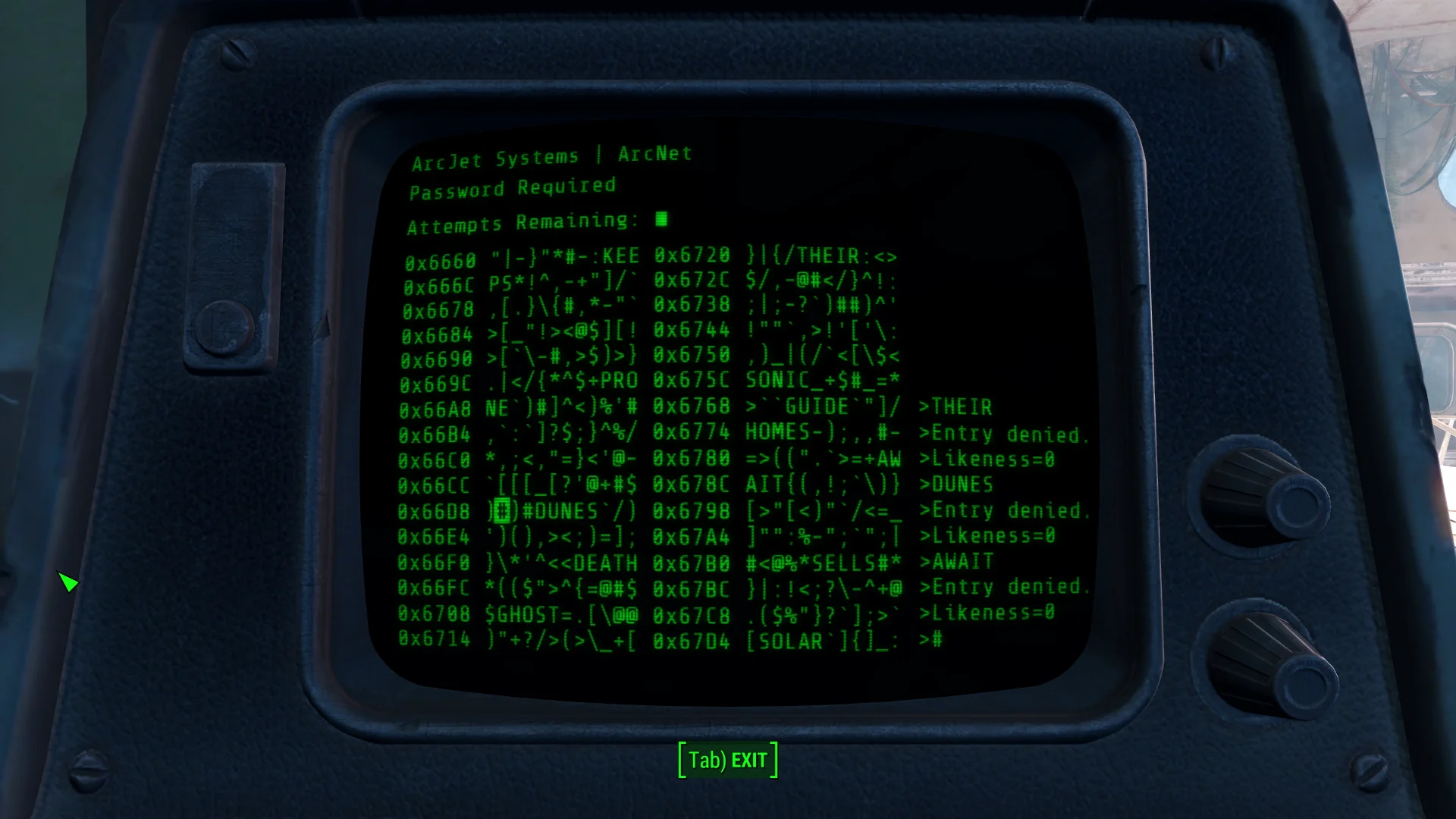

The BASIC interpreter disk can be used to write your own programs. More accurately, the disk actually has Locomotive software’s own version of BASIC, written specifically for the PCW, Mallard BASIC. I thought it might be fun, given the classic green and black terminal look of the PCW, to create a terminal hacking minigame, similar to the one played in a very popular post-apocalyptic game series:

Before we dive in, I should preface this with a disclaimer: Some purists believe learning BASIC is a waste of time, that it ruined early programmers, and that it’s a very clunky and limited language to code in. Dijkstra even wrote, albeit in a very short and tongue-in-cheek text, “It is practically impossible to teach good programming to students that have had a prior exposure to BASIC: as potential programmers they are mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration.” Terrible as it may be, I think BASIC’s limitations and clunkiness will pose a fun challenge for me to make a game using it, and will most likely spark a new appreciation for the quality of life that modern languages give us by comparison!

Basic BASIC

BASIC has some of the building blocks you’d expect to see in modern languages – FOR loops, WHILE loops, IF statements, AND/OR operators, and typing. Variable definitions are implicit, but in earlier versions of BASIC, you had to use the LET keyword. It even has functions – but these are quite different to how we use them in more modern languages; in fact there are 3 ways you may create something resembling a function in BASIC:

DEF FN

Referred to as a “user defined function” in the manual, FNs can take one or more parameters and return an expression. The expression cannot span multiple “lines” (I will get to the mess that is writing lines in BASIC in a moment), however you can chain instructions using colons. The entire expression is returned by this function.

GOSUB

Instructs BASIC to jump to a particular line and execute the code thereon until it finds the RETURN statement. Cannot be parameterised.

GOTO

The worst of the three. Instructs BASIC to jump to a particular line, but does not have a marked “end”. This can make control flow very difficult to follow and should be used incredibly sparingly!

There is also the ON keyword that can be used with GOSUB and GOTO to effectively produce a switch statement, i.e. ON answer GOSUB 100,200,300 where answer is an integer expression which determines the subroutine to be called from the following list. answer = 1 would call 100, answer = 2 would call 200, and so on.

Line numbers in BASIC must be defined by the programmer (in earlier versions of BASIC - later versions didn’t need them), they are not simply built into the editor. Each line you write must be prefaced with a number so that BASIC knows which order to execute them in. For instance:

10 PRINT "Press any key to continue..."

20 WHILE INKEY$="":WEND

30 PRINT "You pressed a key!"

It is advisable to write your line numbers in multiples of 10, in case you need to insert more lines in between them later. Yes, really.

We can make do with this limited control flow, though as you can imagine, programs can get very complicated very quickly, and global variables are unavoidable.

The Minigame

The basic premise of the minigame is this: your goal is to guess a password from a list so you can access a terminal. If you don’t guess it in 4 tries, you are locked out, and with each guess you’re given a clue which tells you how many characters your guess has in common with the answer. The characters have to be in the same position as the answer to be considered a “likeness”.

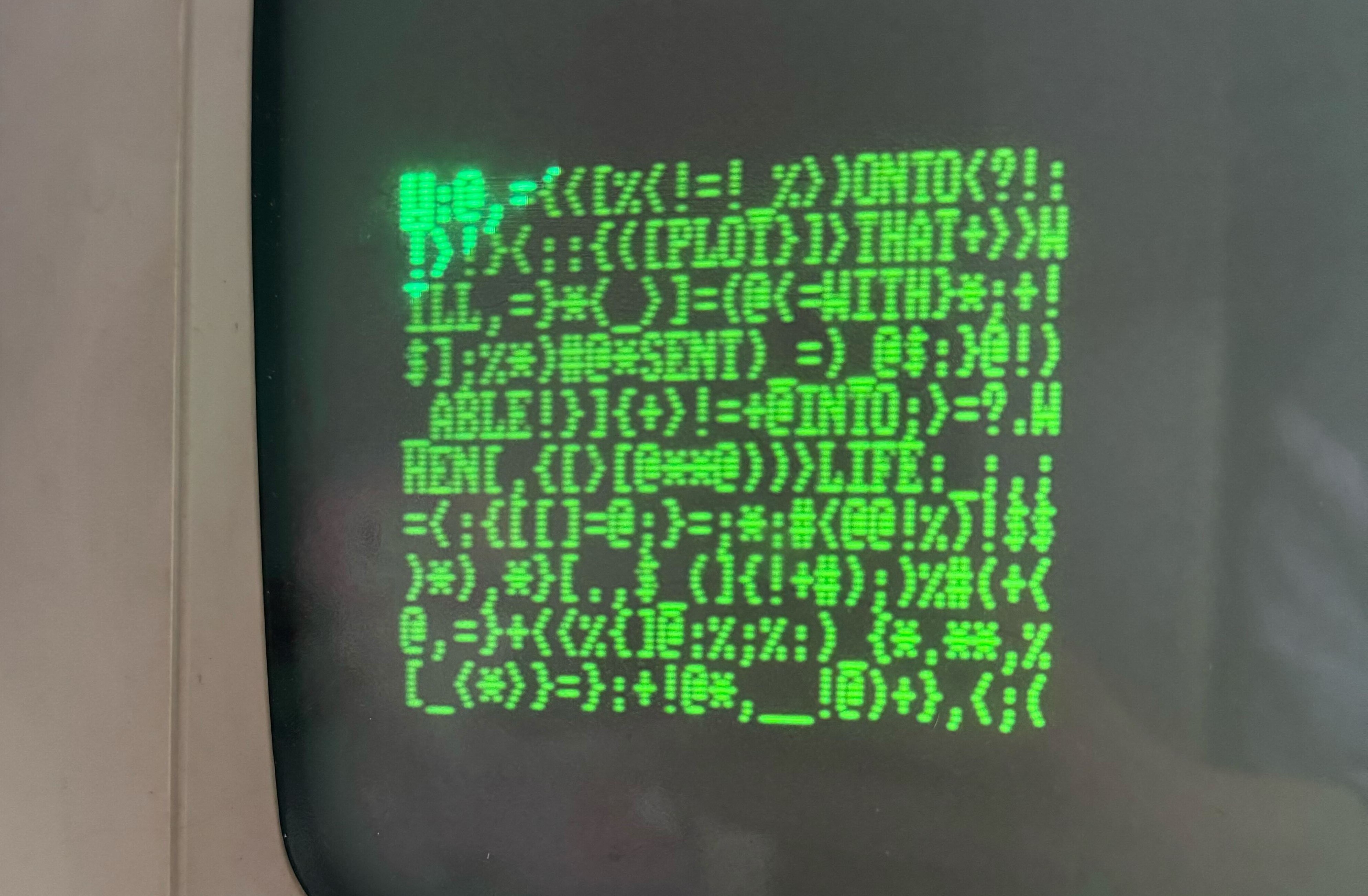

So for instance, if the answer was “GOLF” and your guess was “GOAL”, you’d have a likeness of 2. Referring to our image of the game display, we have a screen of random characters with words to guess inserted at random. Starting with just getting these random characters on the screen, we can write something like:

10 REM ***** Setting up variables *****

20 escape$=CHR$ (27)

30 clear$=escape$+"E"

40 maxChars = 250

50 miscChars$ = "?!:;{}[]()<>_=+@$%*#,."

60 mainStr$ = ""

70 lineno = 1

80 column = 1

90 REM ***** Loop to get random characters from miscChars$ *****

100 FOR i=1 TO maxChars

110 rand = RND*21 + 1

120 mainStr$ = mainStr$ + MID$(misc_chars,rand,1)

130 NEXT

140 REM ***** Setting screen width, clearing, printing the random string *****

150 WIDTH 25

160 PRINT clear$

170 PRINT mainStr$

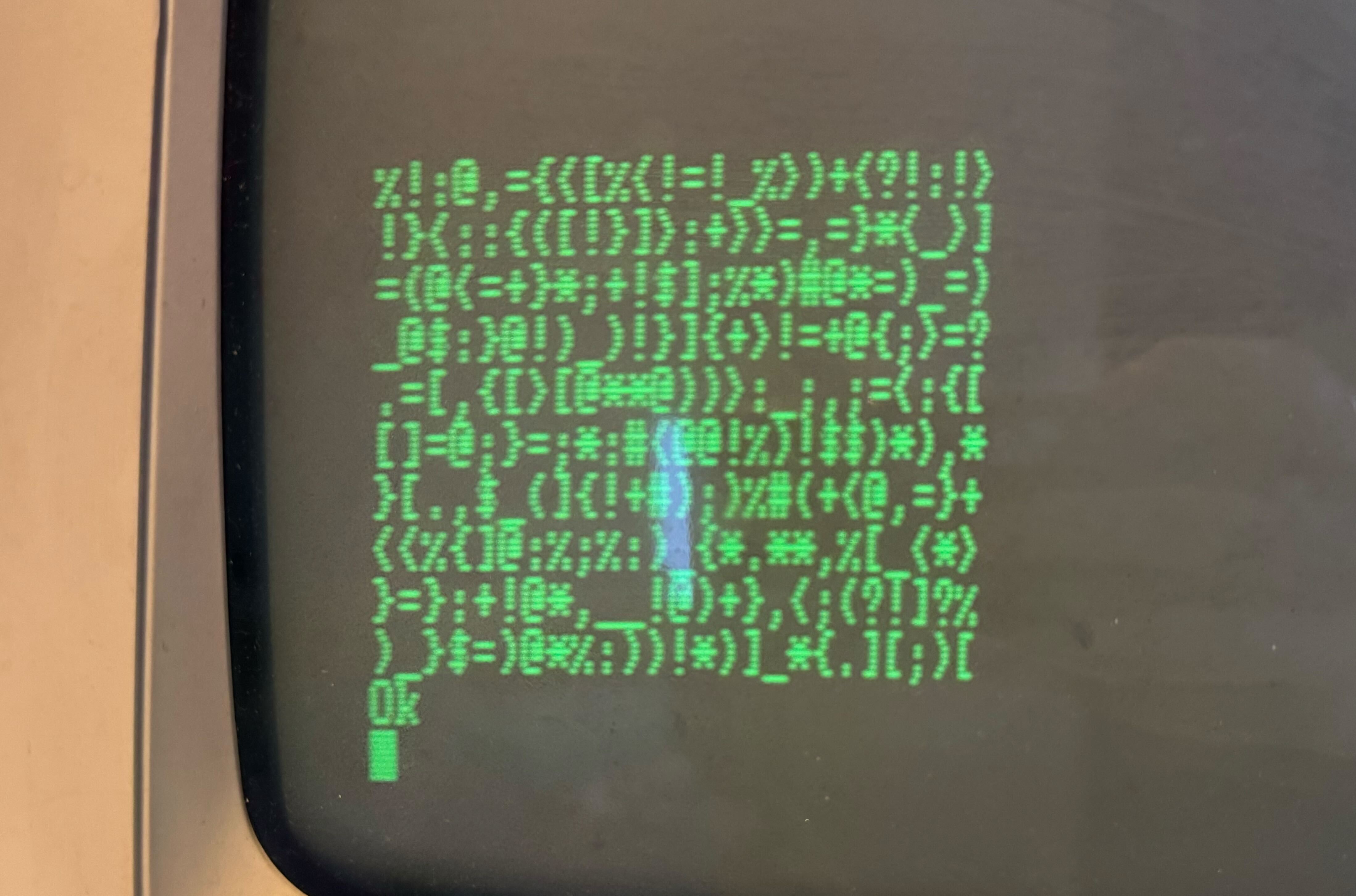

Which gives us:

A few notes about this code:

REMis what we use to indicate comments in BASIC. You can also use a single quote'.- Functions such as clearing the screen (and moving the cursor, but we’ll get to that later) are done by printing special characters that change the state of the screen rather than printing actual readable characters. So, that

clear$variable – made up of ESC + E - clears the screen when printed. - Strings are limited to 255 characters, so to keep things simple, we print 250 characters on the screen. 25 characters per line, 10 lines.

- Some variables and functions (like the built-in

MID$function) have a dollar sign suffix – this is actually a type indicator that tells BASIC this is a string. Without the symbol, the variable is assumed to be a numeric type. - Subroutines called with

GOSUBcannot be parameterised, but we can still use global variables in them, meaning we need to be careful about setting variables before calling the subroutines and considering which variables may be changed by the subroutine itself. - You’ll notice that the interpreter says “Ok” once the program is finished executing - this just means BASIC is ready for the next instruction.

With this information in mind, you can see that this program is defining some variables at the top, constructing a string by picking characters at random from the miscChars$ string, setting the screen width to be 25 characters wide, clearing the screen, and finally, printing our string of random symbols.

We still need to insert some words to guess into this string, but for now I’d like to shift my focus to moving the cursor around by pressing keys, keeping it within the bounds of the 10 x 25 character game area.

Cursor movement isn’t default behaviour while running a BASIC program, so we need to figure out how to do this ourselves. Luckily, there is an INKEY$ variable that can be queried to find the key currently being pressed, and additionally, we can print ESC + Y to move the cursor to different positions around the screen. Using these abilities combined with a game loop, we can add to our existing program:

10 REM ***** Setting up variables *****

20 maxChars = 250

30 miscChars$ = "?!:;{}[]()<>_=+@$%*#,."

40 mainStr$ = ""

50 escape$ = CHR$ (27)

60 move$ = escape$+"Y"

70 clear$ = escape$+"E"

80 gameWon = 0

81 lineno = 19

82 column = 1

90 DEF FNmoveCursor$(lineno, column) = move$+CHR$(lineno+32)+CHR$(column+32)

100 REM ***** Loop to get random characters from miscChars$ *****

110 FOR i=1 TO maxChars

120 rand = RND*21 + 1

130 mainStr$ = mainStr$ + MID$(miscChars$,rand,1)

140 NEXT

150 REM ***** Setting screen width, clearing, printing the random string *****

160 WIDTH 25

170 PRINT clear$;

180 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(19, 0)

190 PRINT mainStr$

200 REM ***** Game Loop *****

210 WHILE gameWon = 0:GOSUB 220:WEND

220 keyPress$ = ""

230 WHILE keypress$="":keypress$=INKEY$:WEND

240 GOSUB 270

250 RETURN

260 REM ***** Detect key presses *****

270 IF keyPress$="w" AND lineno <> 19 THEN lineno = lineno - 1

280 IF keyPress$="s" AND lineno <> 28 THEN lineno = lineno + 1

290 IF keyPress$="a" AND column <> 0 THEN column = column - 1

300 IF keyPress$="d" AND column <> 24 THEN column = column + 1

310 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(lineno, column)

320 RETURN

This gives the following when we run the program:

The Mallard BASIC manual suggests starting any subroutine definitions from at least line 1000 so that they aren’t accidentally executed, and you may want to insert lines between the end of your program and the subroutine definitions. However, BASIC has a really handy command called RENUM which makes all the line numbers evenly spaced in multiples of 10 again, even changing the GOSUB references, so I’m not too worried about having my subroutines begin right after the prior code.

Other versions of BASIC, such as Locomotive BASIC, have a built-in function for moving the cursor, but in Mallard we need to define this ourselves, as shown in FNmoveCursor$.

At first, tracking cursor state seems trivial, given the built-in POS() and LPOS() methods, which return the cursor’s current column and line positions respectively. However, take this excerpt from the manual: “POS returns a logical position on the console, which may bear no relation whatsoever to the current position of the cursor!” And you will see why using this built-in method could prove problematic. There is a similar reference to the LPOS instruction.

The reason that the logical cursor position is different to the current position is likely because, while printing output to the console, BASIC will implicitly insert carriage returns when it reaches the end of a line, so the positions could be offset by these extra hidden characters. It could also be affected by screen scrolling and printing control characters, so this is why it’s safer to track cursor state ourselves.

Now that we have this basic mechanic in place, it’s time to add words at random to the main character string for the player to guess. This involves choosing a word, compounding it with our main string of random characters, and keeping track of where each word is positioned in the string, so that when the player guesses a word, we can find the word they’ve clicked on using the cursor’s position and compare it with the answer.

One of the ways I might normally track word positions is by using a dictionary with each guessable word as the key, and a pair of numerical indices as the value. It will be a little more complicated using BASIC, as it doesn’t have tuples, dictionaries, maps, etc. Array initialisation is also very clunky.

When a user guesses a word, we can instead translate the cursor position to the position it is in the main character array, and loop backwards until we hit a character that exists within the miscChars$ string, which will give us position 0 of the selected word. We can then use this to get the 4-character section of the main string and compare it to the answer.

First, we need to add our word array, select a random word to be the answer, and put the words from the array into the main string:

...

130 DIM words$(10)

140 DATA "ONTO","PLOT","THAT","WILL","WITH","SENT","ABLE","INTO","WHEN","LIFE"

150 FOR i = 1 TO 10

160 READ words$(i)

170 NEXT

180 answer$ = words$(RND * 9 + 1)

...

210 REM ***** Construct random char string *****

220 randChars$ = ""

230 FOR i = 1 TO 10

240 REM * Random number of chars between 10 and 20 *

250 randChLen = RND * 9 + 10

260 REM If mainStr$ has space, get randChLen number of characters

270 IF LEN(mainStr$) < 250 – randChLen THEN GOSUB 560:mainStr$ = mainStr$ + randChars$

280 REM If a word will fit, insert the next word

290 IF LEN(mainStr$) < 246 THEN mainStr$ = mainStr$ + words$(i) ELSE randChLen=250-LEN(mainStr$):GOSUB 560:mainStr$ = mainStr$ + randChars$:i=11

300 NEXT

310 REM If after loop finishes it’s not 250 chars long, top it up

320 IF LEN(mainStr$) < 250 THEN randChLen = 249-LEN(mainStr$):GOSUB 560:mainStr$ = mainStr$ + randChars$

...

550 REM ***** Fetch N amount of random characters *****

560 randChars$ = ""

570 FOR k = 0 TO randChLen

580 randChars$ = randChars$ + MID$(miscChars$, RND*21 + 1, 1)

590 NEXT

600 RETURN

Our output now looks like this:

Now, we need to respond when the user presses “E”, and check the user’s guess against the word using the strategy discussed above. To our code we add:

...

300 IF keyPress$="e" THEN GOSUB 1000

...

1000 REM ***** Set up variables for calculation *****

1010 ln = lineno – 19

1020 col = column + 1

1030 REM The current position of the cursor, translated to mainStr$ index

1040 mainStrCurPos = col + (25 * ln)

1050 REM mainStrWorPos will hold the position of the start of the guessed word

1060 mainStrWorPos = mainStrCurPos

1070 REM * Step back through mainStr$ until we hit a non-letter character *

1080 FOR j = mainStrCurPos TO 0 STEP -1

1090 curPosIsOnLetter = INSTR(miscChars$, MID$(mainStr$, j, 1))

1100 IF curPosIsOnLetter = 0 THEN mainStrWorPos = j ELSE j=-1

1110 NEXT

1120 REM ***** Check if game is won *****

1130 IF MID$(mainStr$, mainStrWorPos, 4) = answer$ THEN PRINT FNmoveCursor$(3,1);"You won!":gameWon = 1

1140 RETURN

Now we have a very basic game that we can win! However, it’s not very obvious to the player when the game is won; in fact, they don’t get a lot of information at all.

There’s a few more features we can add. Firstly, we can add a “likeness” message that tells the player how many letters their guess has in common with the answer. We should also only give them 4 attempts to get the answer, with the game ending after the word has been guessed or the attempts go down to zero. Our main game screen is in the bottom-left corner of the monitor, leaving some space to the right for displaying messages for the user. After printing our initial game grid while the screen width is set to 25, we can then set the width back to 90 and print some messages in the adjacent area by using our FNmoveCursor$ function with an offset column value:

REM ***** Setting up variables *****

...

msgLn = 19

msgCol = 27

attempts = 4

...

REM ***** Set up screen *****

...

WIDTH 90

PRINT FNmoveCursor$(19, 27);"Welcome to HANCO Industries (TM) Termlink"

PRINT FNmoveCursor$(20, 27);"Password Required"

PRINT FNmoveCursor$(21, 27);"Attempts Remaining: ";attempts

We also set msgLn and msgCol variables to track where the next message should be printed, and use an attempts variable in the “Attempts Remaining” message, which we will deduct from when the user makes an incorrect guess. Now, instead of just printing “You won!” in our subroutine that checks the user’s guess against the answer, we can add a GOSUB call to the following code, and make the messages a little more obvious and well-placed:

...

970 REM ***** Check if game is won *****

980 guess$ = MID$(mainStr$, mainStrWorPos, 4)

990 IF guess$ = answer$ THEN PRINT FNmoveCursor$(msgLn, msgCol);"Access Granted.";FNmoveCursor$(32, 0):END ELSE GOSUB 1020

1000 RETURN

1010 '

1020 likeness = 0

1030 FOR m = 1 TO 4

1040 IF MID$(guess$, m, 1) = MID$(answer$, m, 1) THEN likeness = likeness + 1

1050 NEXT

1060 '

1070 attempts = attempts - 1

1080 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(21, 27);"Attempts Remaining: ";attempts

1090 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(msgLn, msgCol);"Entry Denied. Likeness: ";likeness

1100 msgLn = msgLn + 1

1110 '

1120 IF attempts = 0 THEN PRINT FNmoveCursor$(msgLn, msgCol);"Init lockout";FNmoveCursor$(32, 0):END

1130 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(lineno, column)

1140 RETURN

Our game now looks like this:

I haven’t mentioned it yet, but even though we are using the RND function to grab random numbers, the game is actually the same every single time so far. The answer, the placement of the words, and the characters in between each word which are determined by BASIC’s RND function are always the same. This is because BASIC’s pseudo-random number generator calculates the next number based on the previously generated one, and the seed is the same every time, as well as the order in which we generate the numbers for different purposes. We can alter the seed by calling RANDOMIZE with our own number - but how do we come up with that number while keeping every game unique?

I included an initial screen to my game as a solution, where a counter counts up until the user presses a key. The counter’s value is then passed to RANDOMIZE so that each game can be different:

...

240 REM *** Pre-game screen to get random seed ***

250 PRINT clear$;FNmoveCursor$(32, 0);"Press any key to start...";

260 keyPress$ = ""

270 count = 0

280 WHILE keyPress$ = ""

290 keypress$ = INKEY$

300 count = count + 1

310 WEND

320 PRINT "Starting game...";

330 RANDOMIZE count

340 answer$ = words$(RND * 9 + 1)

...

So there we have it: a basic, but fully-working hacking minigame built for the Amstrad PCW! I’ve learned a lot about BASIC along the way, but my main takeaway from this experience is that I have a much bigger appreciation for proper control flow and quality-of-life features that modern languages have today. If you’d like to try running the full program for yourself, I have added the full source code below. Remember you will need a compiler that is compatible with Mallard BASIC!

10 REM ***** Setting up variables *****

20 maxChars = 250

30 miscChars$ = "?!:;{}[]()<>_=+@$%*#,."

40 mainStr$ = ""

50 escape$ = CHR$(27)

60 move$ = escape$+"Y"

70 clear$ = escape$+"E"

80 gameWon = 0

90 lineno = 19

100 column = 0

110 msgLn = 22

120 msgCol = 27

130 attempts = 4

140 '

150 REM ***** Create words array *****

160 DIM words$(10)

170 DATA "ONTO","PLOT","THAT","WILL","WITH","SENT","ABLE","INTO","WHEN","LIFE"

180 FOR i = 1 TO 10

190 READ words$(i)

200 NEXT

210 '

220 DEF FNmoveCursor$(lineno,column) = move$+CHR$(lineno+32)+CHR$(column+32)

230 '

240 REM *** Pre-game screen to get random seed ***

250 PRINT clear$;FNmoveCursor$(32, 0);"Press any key to start...";

260 keyPress$ = ""

270 count = 0

280 WHILE keyPress$ = ""

290 keypress$ = INKEY$

300 count = count + 1

310 WEND

320 PRINT "Starting game...";

330 RANDOMIZE count

340 answer$ = words$(RND * 9 + 1)

350 '

360 REM ***** Construct random char string *****

370 randChars$ = ""

380 FOR i = 1 TO 10

390 REM * Random number of chars between 10 and 20 *

400 randChLen = RND * 9 + 10

410 REM If mainStr$ has space, get randChLen number of characters

420 IF LEN(mainStr$) < 250 - randChLen THEN GOSUB 760:mainStr$ = mainStr$ + randChars$

430 REM If a word will fit, insert next word

440 IF LEN(mainStr$ < 246 THEN mainStr$ = mainStr$ + words$(i) ELSE randChLen = 250 - LEN(mainStr$):GOSUB 760:mainStr$ + randChars$:i = 11

450 NEXT

460 '

470 REM If after loop finishes it's not yet 250 chars long, top it up

480 IF LEN(mainStr$) < 250 THEN randChLen = 249 - LEN(mainStr$):GOSUB 760:mainStr$ = mainStr$ + randChars$

490 '

500 REM ***** Set up screen *****

510 WIDTH 25

520 PRINT clear$;

530 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(18, 0);mainStr$;

540 WIDTH 90

550 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(19, 27);"Welcome to HANCO Industries (TM) Termlink"

560 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(20, 27);"Password Required"

570 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(21, 27);"Attempts Remaining: ";attempts

580 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(19, 0);

590 '

600 REM ***** Game loop *****

610 WHILE gameWon = 0:GOSUB 620:WEND

620 keyPress$ = ""

630 WHILE keyPress$ = "":keyPress$ = INKEY$:WEND

640 GOSUB 680

650 RETURN

660 '

670 REM ***** Key press subroutine *****

680 IF keyPress$="w" AND lineno <> 19 THEN lineno = lineno - 1

690 IF keyPress$="s" AND lineno <> 28 THEN lineno = lineno + 1

700 IF keyPress$="a" AND column <> 0 THEN column = column - 1

710 IF keyPress$="d" AND column <> 24 THEN column = column + 1

720 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(lineno, column);

730 IF keyPress$="e" THEN GOSUB 840

740 RETURN

750 '

760 REM ***** Fetch N amount of random characters *****

770 randChars$ = ""

780 FOR k = 0 TO randChLen

790 randChars$ = randChars$ + MID$(miscChars$, RND*21 + 1, 1)

800 NEXT

810 RETURN

820 '

830 REM ***** Set up variables for calculation *****

840 ln = lineno - 19

850 col = column + 1

860 REM The current position of the cursor, translated to mainStr$ index

870 mainStrCurPos = col + (25 * ln)

880 REM mainStrWorPos will hold the position of the start of the guessed word

890 mainStrWorPos = mainStrCurPos

900 REM * Step back through mainStr$ until we hit a non-letter character *

910 FOR j = mainStrCurPos TO 0 STEP -1

920 letter$ = MID$(mainStr$, j, 1)

930 curPosIsOnLetter = INSTR(miscChars$, letter$)

940 IF curPosIsOnLetter = 0 THEN mainStrWorPos = j ELSE j = -1

950 NEXT

960 '

970 REM ***** Check if game is won *****

980 guess$ = MID$(mainStr$, mainStrWorPos, 4)

990 IF guess$ = answer$ THEN PRINT FNmoveCursor$(msgLn, msgCol);"Access Granted.";FNmoveCursor$(32, 0):END ELSE GOSUB 1020

1000 RETURN

1010 '

1020 likeness = 0

1030 FOR m = 1 TO 4

1040 IF MID$(guess$, m, 1) = MID$(answer$, m, 1) THEN likeness = likeness + 1

1050 NEXT

1060 '

1070 attempts = attempts - 1

1080 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(21, 27);"Attempts Remaining: ";attempts

1090 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(msgLn, msgCol);"Entry Denied. Likeness: ";likeness

1100 msgLn = msgLn + 1

1110 '

1120 IF attempts = 0 THEN PRINT FNmoveCursor$(msgLn, msgCol);"Init lockout";FNmoveCursor$(32, 0):END

1130 PRINT FNmoveCursor$(lineno, column)

1140 RETURN