This post is a continuation of my previous which looked at implementing Conway’s Game of Life using functional techniques. Here I look at how memoization can be used to cache the return value of a function in order to improve performance.

Introduction

In my previous post I discussed an implementation of Life which was free from for-loops, instead relying on functional techniques. The core logic, which operates on an n x n grid of cells, is shown below:

func iterate() {

// utility functions

// local function, hence defined as constant closures

let cellsAreNeighbours = {

(op1: Cell, op2: Cell) -> Bool in

let delta = (abs(op1.x - op2.x), abs(op1.y - op2.y))

switch (delta) {

case (1,1), (1,0), (0,1):

return true

default:

return false

}

}

let neighboursForCell = {

(cell: Cell) -> [Cell] in

return self.cells.filter { cellsAreNeighbours(cell, $0)}

}

let livingNeighboursForCell = {

(cell: Cell) -> Int in

neighboursForCell(cell).filter{ $0.state == State.Alive }.count

}

// rules of life

let liveCells = cells.filter { $0.state == .Alive }

let deadCells = cells.filter { $0.state != .Alive }

let dyingCells = liveCells.filter { livingNeighboursForCell($0) !~= 2...3 }

let newLife = deadCells.filter { livingNeighboursForCell($0) == 3 }

// updating the world state

newLife.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Alive }

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }The iterate function is roughly split into three sections:

- Local utility functions, defined as closure expressions.

- The rules of Life where cells that are dying or contain new life are identified.

- The section where the world state is updated.

Whilst the above code is expressive and self-contained, the performance issues are immediately apparent - the n x n structure of the cells never changes, therefore repeatedly computing the neighbours for a given cell is quite wasteful.

Before going ahead and optimising the above code it is probably worth determining whether this is in fact necessary. Optimising code which doesn’t need to run any faster is a waste of time!

Performance testing

Ideally I’d like the game to run at around 20 frames per second, which gives me a good target metric for my optimisation.

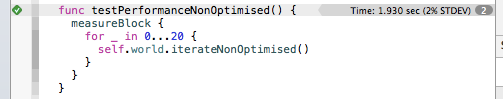

The Xcode unit testing tools have a built-in mechanism for performance measurement. By adding a measureBlock to a unit, the test runner will repeatedly execute the supplied closure in order to determine its average execution time:

As you can see from the above, the current, non-optimised version of my Life game takes around 2 seconds to perform 20 iterations, so fails to meet my target of 20 frames per second.

A memoize function

Memoization (which my spell checker ironically keeps trying to correct to memorisation) is an optimisation technique where the return values of a function are cached to avoid repeating the same computation.

The neighbours for a cell never change, so the result from neighboursForCell needs to be cached at the scope of the World class, rather than within the iterate method itself.

The simplest approach is to make this function a lazy property:

class World {

...

lazy var neighboursForCell: (cell: Cell) -> [Cell] = {

(cell: Cell) -> [Cell] in

let cellsAreNeighbours = {

(op1: Cell, op2: Cell) -> Bool in

let delta = (abs(op1.x - op2.x), abs(op1.y - op2.y))

switch (delta) {

case (1,1), (1,0), (0,1):

return true

default:

return false

}

}

return self.cells.filter { cellsAreNeighbours(cell, $0)}

}

...

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }Notice that the cellsAreNeighbours function which this depends on has been nested.

In order to memoize this function it needs to be adapted by wrapping it in a function that caches its return value. The first-class nature of Swift functions means that this is surprisingly simple to achieve:

func memoize<T:Hashable, U>(fn : T -> U) -> T -> U {

var cache = [T:U]()

return {

(val : T) -> U in

if cache.indexForKey(val) == nil {

cache[val] = fn(val)

}

return cache[val]!

}

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }With its mixture of generics and functional parameters this code might look a little formidable! Here’s how the various pieces fit together!

- The

memoizesignature is(fn : T -> U) -> T -> U, this indicates that it takes a single parameter, namedfn, of typeT -> U. In other words, this parameter is itself a function that takes a single parameter of typeTand returns a valueU. The return type ofmemoizeisT -> U, which is a function of the same type as the parameter that is passed in tomemoize. The signature might be a little easier to read with added parentheses around the function types(fn : (T -> U)) -> (T -> U) - The first line of the function defines a dictionary of type

[T:U], where the key is the input type of the function being memoized and the value is the output type. Dictionary keys must be hashable, which explains the type constraints for the memoize function<T:Hashable, U> - The next line defines and returns a closure expression, which has the same type (i.e. signature) as the function being memoized. This closure checks to see whether the cache contains a value for the given input. If not, the

fnargument is used to call the original function to obtain a value. The final line returns the value from the cache - Notice that the

cachevariable will be captured by the closure.

Memoization, simple to implement, a little tricky to understand!

So now that we have a mechanism for memoizing functions, how is it used? Simple, just add memoize in front of the closure expression:

lazy var neighboursForCell: (cell: Cell) -> [Cell] = memoize {

// see the earlier implementation

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }The trailing closure syntax is highly effective in this context.

Memoization in action

Unfortunately the above code will not compile because Cell does not adopt the Hashable protocol (and by inheritance the Equatable protocol as well). This is easily rectified as follows:

class Cell: Hashable {

let x: Int, y: Int

...

var hashValue: Int {

return x + y * 1_000;

}

...

}

func == (lhs: Cell, rhs: Cell) -> Bool {

return lhs.x == rhs.x && lhs.y == rhs.y

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }The Hashable protocol is used to create a hash-value for an instance of an object. This value is used to partition values within dictionaries in order to improve look-up times. A good hash-value implementation minimises collisions resulting in improved look-up performance. These cells are occupy an n x n grid, so the above implementation will ensure unique hash codes for cells used in grids of up to 1,000 rows or columns. That’ll do quite nicely!

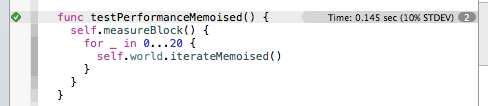

Now that function that finds the neighbours for a cell is memoized, it’s time to test performance once again:

This gives 0.145 secs, a big improvement on 1.93 secs, and enough to hit the target of 20 frames per second.

Faster memoization

There is one small problem with the current memoize function, it is a little slow! If you look closely, each time it is called for a cached value the indexForKey function is called on the dictionary, followed by the subscript, cache[val], this effectively results in two dictionary lookups!

A faster method, that is optimised so that cache ‘hits’ only require a single dictionary operation is given below:

func memoize<T:Hashable, U>(fn : T -> U) -> T -> U {

var cache = [T:U]()

return {

(val : T) -> U in

var value = cache[val]

if value != nil {

return value!

} else {

let newValue = fn(val)

cache[val] = newValue

return newValue

}

}

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }The above is slightly more verbose, but results in the test execution dropping further to 0.101 seconds.

Pre-computation

Rather than going to all this trouble of caching function value, each cell could simply store a reference to its neighbours:

class Cell: Hashable {

...

var neighbours: [Cell]

...

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }With this new property being pre-populated when the World is initialised:

init() {

cells = [Cell]()

// create the cells

for x in 0..<dimensions {

for y in 0..<dimensions {

cells.append(Cell(x: x, y: y))

}

}

// find their neighbours

for cell in cells {

cell.neighbours = self.neighboursForCell(cell: cell)

}

}

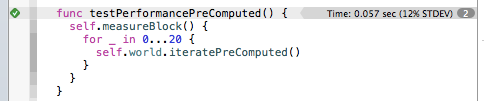

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }Using the neighbours property on the cell, rather than the memoized function, further improves performance to 0.057 seconds:

So, does this mean that memoization is a pointless and complicated concept? No. It simply means that the Game of Life is simpler and more performant without it!

Memoization is a useful and powerful concept that the Swift language fully supports.

Memoization of multi-parameter functions

You might have noticed a rather big limitation of the current memoize function … the signature of the function it adapts T -> U, only has a single parameter. What if you want to memoize functions with multiple parameters?

Unfortunately the strictness of the type system and lack of reflection means that there is no generic way to achieve this. Or should I say, I haven’t found a way to achieve it, if you have, I’d love to know!

You can however define a memoize function for functions of two hash able parameters. In order to support this, the two parameters need to be combined into a single value to be used as the key in the cache:

A simple struct will do the trick:

struct FunctionParams<T:Hashable, S:Hashable> : Hashable {

let x: T, y: S

var hashValue: Int {

var hash = 17;

hash = hash * 23 + x.hashValue

hash = hash * 23 + y.hashValue

return hash;

}

}

func ==<T:Hashable, S:Hashable>

(lhs: FunctionParams<T, S>, rhs: FunctionParams<T, S>) -> Bool {

return lhs.x == rhs.x && lhs.y == rhs.y

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }The memoize function simply needs to ‘wrap’ the function arguments in this struct in order to cache the return value:

func memoize<S:Hashable, T:Hashable, U>(fn : (S, T) -> U) -> (S, T) -> U {

var cache = Dictionary<FunctionParams<S,T>, U>()

func memoized(val1 : S, val2: T) -> U {

let key = FunctionParams(x: val1, y: val2)

if cache.indexForKey(key) == nil {

cache[key] = fn(val1, val2)

}

return cache[key]!

}

return memoized

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }You can now memoize functions with two parameters:

let cellsAreNeighbours = memoize {

(op1: Cell, op2: Cell) -> Bool in

...

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }Awesome!

Conclusions (And the elephant in the room)

Hopefully you have enjoyed learning about memoization. The functional nature of the Swift language certainly makes these concepts much more easy to apply than Objective-C. As a parting thought, I just want to address the elephant in the room …

The function being memoized find all the neighbours for a given cell by checking whether each of the other cells in the World is a neighbour:

lazy var neighboursForCell: (cell: Cell) -> [Cell] = memoize {

(cell: Cell) -> [Cell] in

...

return self.cells.filter { cellsAreNeighbours(cell, $0)}

}

dyingCells.each { (cell: Cell) in cell.state = .Dead }This is of course a tremendously slow way of finding the neighbours in the first place!

But if I had presented a fast implementation originally (and one that was possibly less functional - _gasps!_), this blog post about memoization would never have been written ;-)

Regards, Colin E.