I recently had the opportunity to help implement some of the functionality of D3FC in WebGL. D3FC is a library which extends the D3 library, providing commonly used components to make it easier to build interactive charts.

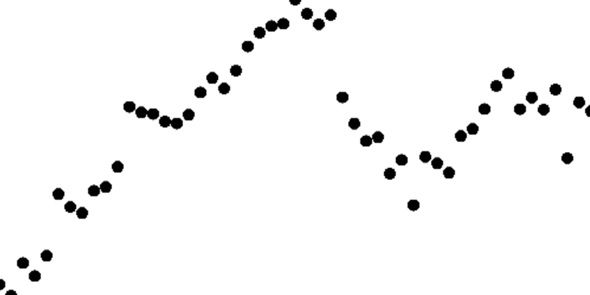

D3FC was initially created using an SVG implementation. A Canvas implementation was later added, which was generally faster than SVG by an order of magnitude. It still performs slowly, however, when handling more than 10,000 points.

WebGL is a GPU accelerated 3D framework which provides a JavaScript API. By using this to render 2D graphics, we are hoping to render a few orders-of-magnitude faster than Canvas (for a demonstration of this, see Andy Lee’s example)

Running code on the GPU is significantly quicker than JavaScript, so we want to pass over as much work as possible.

How Does WebGL Work?

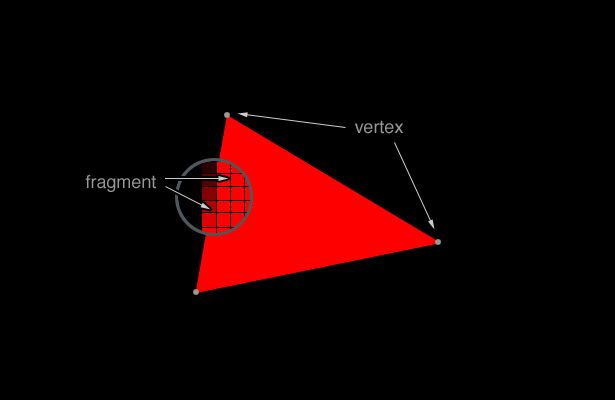

Everything rendered by WebGL is built using triangles. To construct these triangles, we need to define two things - the locations of the vertices and the colour of the individual pixels (or fragments) within the triangle.

These triangles can be combined to generate detailed, 3D visualisations (check out this aquarium example). However, we only need to worry about 2D environments, which removes a lot of the complexity of WebGL. For instance, we don’t need to worry about lighting or textures.

We define the vertices and the fragments using the creatively named vertex shader and fragment shader. The vertex shader is called for each vertex and sets the position of that vertex. Similarly, the fragment shader is called for each pixel and determines the colour of that pixel.

Our job, as the developers, is simple:

- Define the shaders.

- Pass the data and any other variables to the GPU with buffers.

- Hand our shaders to the GPU.

- Let the magic happen.

Sounds easy enough, but how do we do all this in practice?

Making a simple D3FC component that renders to WebGL is quite easy. We convert our series data to “triangles”, load them into the buffers, and render them using simple shaders. To maximise our performance, however, we want to minimise the number of triangles and move as much computation to the shaders as possible.

This blog explores one approach to this process, looking at how to render circular points with minimal data transferred across buffers and making best use of the shaders.

Drawing squares

Because each shape has equal height and width, we can perform most of the calculations in the fragment shader without too much waste. Our vertex shader can return a square big enough to contain the shape, and the fragment shader will discard any pixels that aren’t needed.

We need to calculate the length of the edges of the square, which we’ll call vSize. Since we know the area we want our symbol to fill, we can work backwards to calculate vSize. For example, to calculate vSize for a circle:

attribute float aSize; // The area of the shape

varying float vSize; // The length of the edge of the square containing the shape

vSize = 2.0 * sqrt(aSize / 3.14159); // Calculate the diameter of the circle from the area

We pass in aSize into the buffers, and our vertex shader uses this to calculate vSize. Because vSize is varying, it can be passed to the fragment shader.

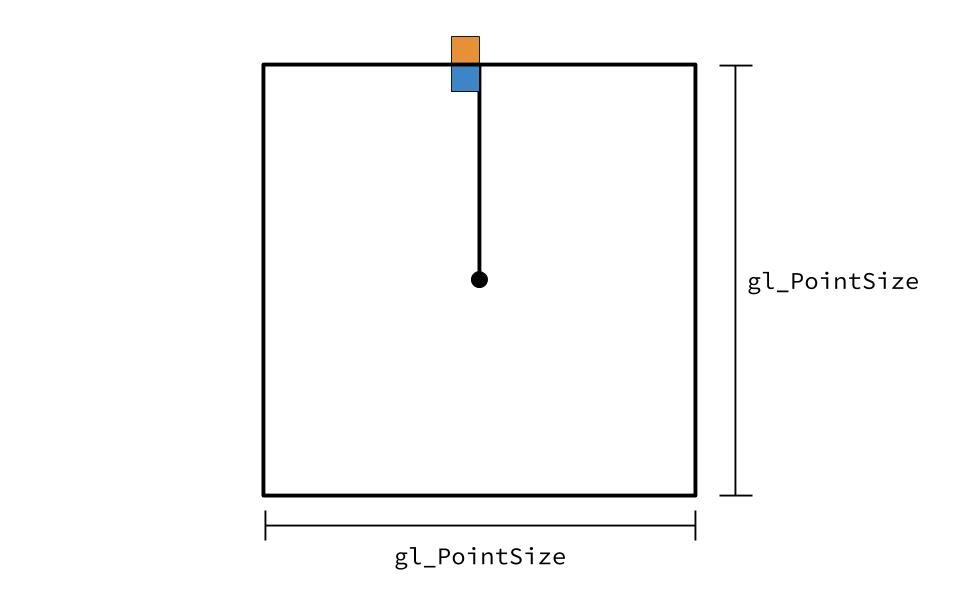

The vertex shader also needs to define two variables - the point size (gl_PointSize) and the point’s coordinates (gl_Position).

gl_Position is a vector with four components (vec4). The first three components represent the x, y, and z coordinates of the point. We’ll pass the x and y coordinates in through the buffers. Since we’re working in 2D space, we don’t have to worry about the z coordinate, so we’ll set it to 0.

The 4th component of gl_Position changes this point into a homogeneous coordinate. This is useful when manipulating 3D data. In our case though, we’ll leave it as the default of 1.

attribute float aXValue;

attribute float aYValue;

gl_Position = vec4(aXValue, aYValue, 0, 1);

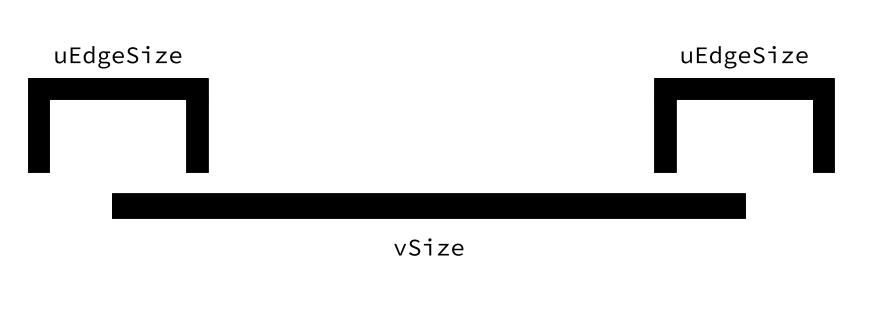

gl_PointSize will be the length of the square (vSize) plus any extra length added by the edge (we’ll use this to add a “stroke” to the points later). We can see what this extra length is by imagining the shape lying flat with the edge as a separate layer above it.

Each edge is half within the shape and half without. This means the point size becomes vSize + (0.5 * uEdgeSize) + (0.5 * uEdgeSize), or vSize + uEdgeSize.

In theory, we’re done. In practice, however, there’s one more thing we need.

The value we just calculated is continuous. However, we’ll be drawing to discrete pixels. This, in addition to only using an approximate value for pi and floating-point errors, can lead to aliasing.

If one of our shape’s outer pixel is less than gl_PointSize (the blue pixel), then it will render fine. However, if the outer pixel is just outside gl_PointSize (the orange pixel), then it will be cut off. To prevent this, we’ll add 1 to our gl_PointSize to ensure the shape’s outer pixels are always rendered.

uniform float uEdgeSize;

gl_PointSize = vSize + uEdgeSize + 1.0;

Put this all together, and we have a vertex shader drawing our correctly sized shapes.

So far our circles are looking quite… not round. So let’s jump over to the fragment shader and find the statue hidden in the marble.

Drawing circles

For each pixel of the square, we need to determine whether it is within the shape and if not, discard the pixel. For a circle, this is straightforward - we calculate the distance from the pixel to the centre.

The vertex shader transforms our coordinates into a different coordinate system called clip space. Clip space is a cube that is two units wide and contains the points from one corner (-1, -1, -1) to other (1, 1, 1).

To convert our points to clip space, we can use gl_PointCoord. gl_PointCoord gives us the two-dimensional coordinates of the point, ranging from 0.0 to 1.0 in both directions. Therefore, to convert gl_PointCoord to clip space, we can use (2.0 * gl_PointCoord) - 1.0.

Once we map our point to clip space, we can discard any pixels which have a greater distance to (0, 0, 0) than 1. To calculate the distance, we can use length, which will calculate the length of the vector (or, in other words, the distance from the point to the origin).

varying float vSize;

float distance = length(2.0 * gl_PointCoord - 1.0);

if (distance > 1.0) {

discard;

}

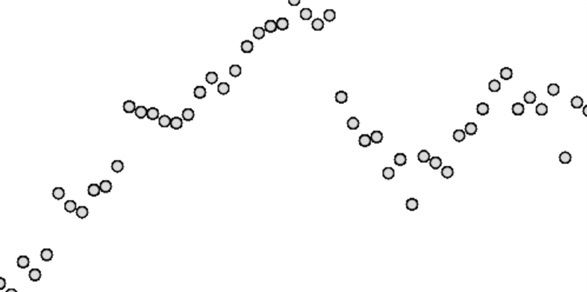

That’s more like it! Instead of black circles, though, it’d be nice to be able to decorate the points - change the colour, add a border, etc.

Decorating circles

Changing the colour is uncomplicated. We pass the colour into the buffers and then set gl_FragColor to that colour in the fragment shader.

uniform vec4 uColor;

gl_FragColor = uColor;

Adding the border is more complicated. We need to calculate whether the pixel we’re looking at is on the border and, if it is, colour the pixel the edge colour. Sounds simple but a lot is going on here so let’s break it down.

We create a variable called sEdge, which will be a float between 0.0 and 1.0. When sEdge is 0.0, we keep the existing gl_FragColor. When it is 1.0, we set gl_FragColor to uEdgeColor, which is passed in through the buffer. Any number in between will result in a blend between the two colours.

How do we calculate sEdge? It’s easier to see what’s happening in 1D. Imagine a line being drawn from the centre of the shape to the edge. Part of that line will be the shape colour and part will be the border colour. We need a function that will set sEdge to 0.0 at the points of the line where it should be the shape colour, 1.0 at the border and a number in between during the transition between the two. We’ll use the intermediate numbers to smooth the transition. This reduces the aliasing that can occur when square pixels try to represent a curved edge.

Fortunately, WebGL provides us with that function. smoothstep takes three arguments: edge0, edge1 and x.

- If

xis less thanedge0, the function returns 0.0. - If

xis greater thanedge1. the function returns 1.0. - If

xis in betweenedge0andedge1, the function returns a number between 0.0 and 1.0, using a Hermite polynomial.

We’re nearly there - we now need to figure out what edge0, edge1 and x are.

edge1 is where the edge starts, so it is vSize - uEdgeSize.

edge0 is where the colour transition starts, so it is edge1 minus the size of the “transition gap” (where the sEdge is transitioning from 0.0 to 1.0). The greater we set this number, the greater the smoothing of the transition between the shape colour and the edge colour. A smaller number increases the sharpness of the transition but also increases the probability of aliasing.

2.0 removes the aliasing while maintaining the sharp line that we want, so we’ll set edge0 as vSize - uEdgeSize - 2.0.

Because we previously represented distance in clip space, it is a number between 0 and 1. We can use this number as the fraction of the total distance of the pixel from the centre to the edge of the shape. For example, if distance = 0.5, the pixel is halfway between the centre and the edge. Thus, to calculate where the pixel is, we need to multiply distance by the point size. This gives us x = distance * (vSize + uEdgeSize).

Put all this together, and we have our answer!

uniform vec4 uEdgeColor;

uniform float uEdgeSize;

float sEdge = smoothstep(

vSize - uEdgeSize - 2.0,

vSize - uEdgeSize,

distance * (vSize + uEdgeSize)

);

gl_FragColor = (uEdgeColor * sEdge) + ((1.0 - sEdge) * gl_FragColor);

Ok, we’re almost done, there’s one last thing to handle. If you look closely at the edges of the circles, you can see they’re still jagged. So our final step is to implement some anti-aliasing.

Anti-aliasing circles

We’ll use a similar technique as before, but instead of smoothing the shape colour into the border, we’ll smooth the border colour into the background. We’ll choose a transition size of 2.0 for the same reasons as before.

gl_FragColor.a = gl_FragColor.a * (1.0 - smoothstep(

vSize - 2.0,

vSize,

distance * vSize

));

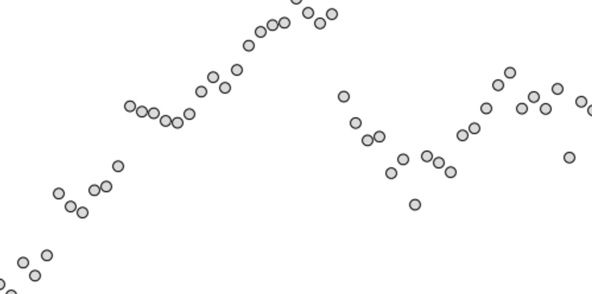

And we’re done!

Other shapes

Although we’ve used circles as an example, the same principles apply for any shape. All that needs to be adapted are the calculations for vSize and distance.

In the case of other shapes, distance won’t be the actual distance but a number which is greater than 1.0 only for the pixels which lie outside the shape. For example, distance for a square could be calculated with:

vec2 pointCoordTransform = 2.0 * gl_PointCoord - 1.0;

float distance = max(abs(pointCoordTransform.x), abs(pointCoordTransform.y));

Here we once again convert gl_PointCoord to clip space. We take the maximum absolute value of the x and y coordinate. In this way, if either the x or y coordinate is greater than 1.0 (or less than -1.0), we know it is outside of the square and can be discarded.

Conclusion - Why are we doing this again?

Using this approach has plenty of advantages.

GL_POINT works well when drawing a large number of small 2D items. If we used GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP, for example, we’d have to calculate how to draw each shape using triangles. Using each vertex as a point means we don’t have to worry about geometry.

In addition, procedural rendering of the shape in the fragment shader is fast. It also still allows changes in size without resulting in scaling artifacts.