I recently had the opportunity to help implement some of the functionality of D3FC in WebGL. D3FC is a library which extends the D3 library, providing commonly used components to make it easier to build interactive charts.

In my last post, I discussed the approach we’ve taken to draw points in WebGL. We created a series of squares in the vertex shader before discarding any unneeded pixels in the fragment shader. The shapes had similar heights and widths, so this worked well - the fragment shader needed to discard relatively few pixels.

This technique, however, won’t be suitable for drawing lines. Lines are typically long and thin, which means that the fragment shader would have to run on a significantly higher number of pixels which aren’t needed.

Also, our points need to be connected, which means GL_POINT won’t be the best immediate mode to use.

This blog explores a different approach to rendering in WebGL, looking at how to render lines with minimal data transferred across buffers and making best use of the shaders.

Drawing rectangles

Everything in WebGL is built using triangles. We can place two triangles next to each other to create a rectangle.

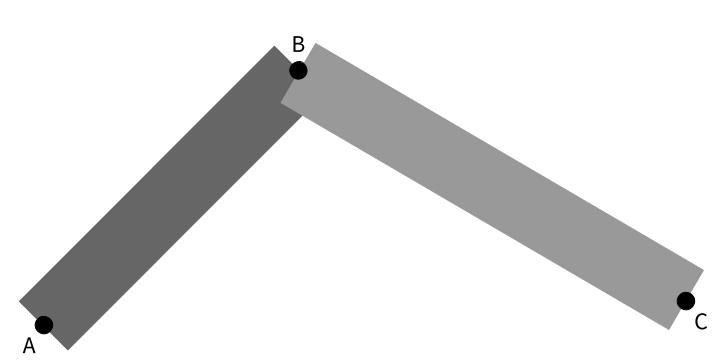

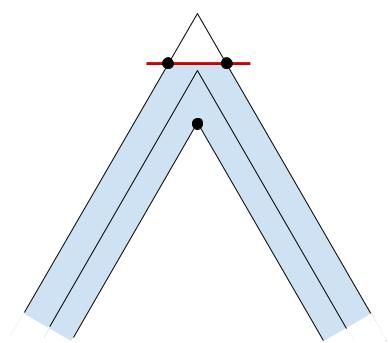

Our first idea might be to connect each point to the next by drawing a rectangle between them. When we try this, however, we see that there is a problem with this technique.

The two rectangles leave a dip at the top. So we’ll need to think of a better way to join the points.

Drawing trapeziums

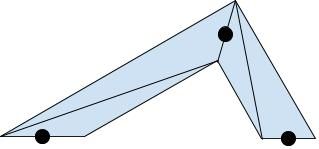

Instead of rectangles, we could draw trapeziums. These would allow us to fit two together without any overlap or gaps. This type of joint is called a miter.

How would we do this in the vertex shader?

We can take advantage of GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP. A triangle strip is a series of triangles which share vertices. We only have to define each vertex once, and WebGL will connect the triangles into a strip.

We’ll need two vertices for each point - one for the outer join of the lines and one for the inner.

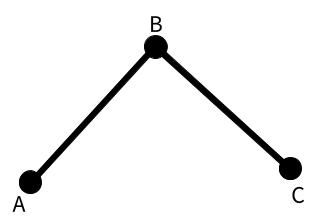

For simplicity, we’ll assume we’re drawing a line with three points: A, B, and C. B is the current point being considered by the vertex shader, A is the previous point, and C is the next point. We can pass in these values through the buffers.

To correctly translate the points to the vertices of the triangles, we need to know two things: how far to move them and in which direction.

Our result will look something like this.

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy + (directionToMove * distanceToMove);

Direction

To help us calculate the direction of the miter, we can use the miter tool which was developed by Tom McLaughlan. As you can see, the miter line is the normal vector to the tangent of the lines AB and BC. So if we find the tangent, we can use that to calculate the direction.

We can calculate the tangent by adding the normalized vectors AB and BC.

Finally, to calculate AB and BC, we can subtract one point’s coordinates from the other, and then normalize the vector.

vec2 AB = normalize(gl_Position.xy - prev.xy);

vec2 BC = normalize(next.xy - gl_Position.xy);

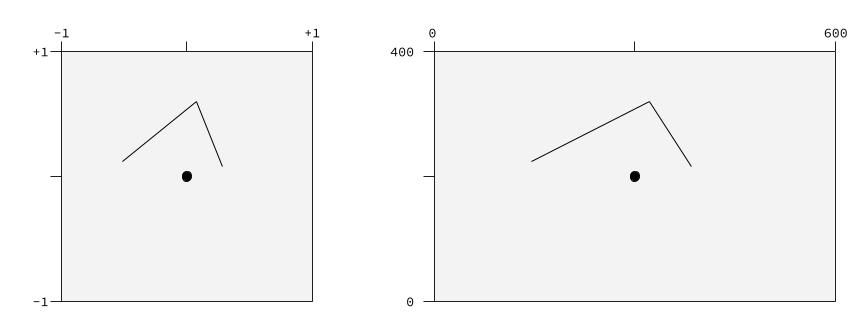

gl_Position gives us the current vertex’s position in clip space. The clip space ranges from -1 to +1 in both directions and so is a square. However, the canvas we are drawing to is more likely to be a rectangle. This isn’t usually a problem, because the canvas size is mapped to clip space. One side effect of this mapping, though, is that the angles of the vectors in clip space are not the same as they will be on our canvas.

We will be needing the angles from the screen space, rather than clip space, so we’ll multiply our AB and BC vectors by the screen size, uScreen, to ensure we have the correct aspect ratio.

vec2 AB = normalize(normalize(gl_Position.xy - prev.xy) * uScreen);

vec2 BC = normalize(normalize(next.xy - gl_Position.xy) * uScreen);

vec2 tangent = normalize(AB + BC);

We’re normalizing the tangent because we only care about the direction of the vector. We want whatever value we calculate for the vector to have a distance of 1 so that we can multiply it by the distance to get the correct value at the end.

There’s just one problem. If the previous or next point is at the same location as the current point, our vector will be (0, 0) and won’t be able to be normalized. To get around this, we can move the previous (or next) point in the opposite direction to the next (or previous) point, so that the three points are in a straight line. This won’t affect how the line is drawn, we’ll only use the calculated point to allow us to correctly calculate the tangent.

if (all(equal(gl_Position.xy, prev.xy))) {

prev.xy = gl_Position.xy + normalize(gl_Position.xy - next.xy);

}

if (all(equal(gl_Position.xy, next.xy))) {

next.xy = gl_Position.xy + normalize(gl_Position.xy - prev.xy);

}

Now that we have the tangent, we can rotate it 90° to give us the miter.

vec2 miter = vec2(-tangent.y, tangent.x);

And that gives us the miter’s direction.

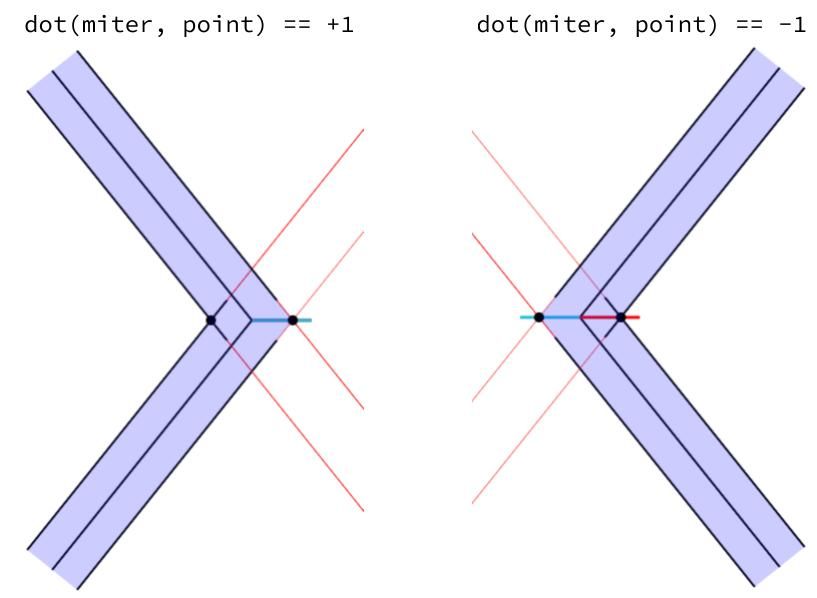

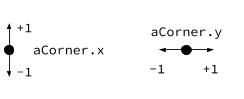

Well, it gives us one of them. If we look back at our miter tool image, we can see the miter gives us the direction to one of the vertices (the inner join in this case), but there’s another vertex in the opposite direction. Because we’re using two vertices per point, we need a way to tell one vertex to go in the direction of the miter and the other vertex to go in the opposite direction. We do this by loading in another array into the buffers: aCorner. The value from this attribute will either be +1 or -1, indicating which direction that vertex should go.

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy + (aCorner.x * miter * distanceToMove);

You may notice we’re using aCorner.x. Later on, we’ll need aCorner.y but for now, don’t worry about it.

Distance

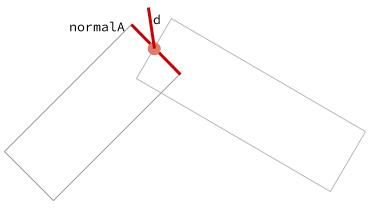

To calculate the correct length (d), let’s take another look at our line when we used rectangles.

d can be found by projecting it on one of the normals (in this case, normalA) by using the dot product. normalA is the normal vector to the line AB and is the short side of the rectangle in the image above (shown in red).

We calculate normalA in the same way that we calculated the miter direction from the tangent.

vec2 normalA = vec2(-AB.y, AB.x);

d = widthOfLine / dot(miter, normalA);

The width (or thickness) of the line can be passed in through the buffers and loaded as a uniform, uWidth.

float miterLength = 1.0 / dot(miter, normalA);

// directionToMove = aCorner.x * miter;

// distanceToMove = uWidth * miterLength;

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy + (aCorner.x * miter * uWidth * miterLength) / uScreen.xy;

Notice that we are also dividing by uScreen.xy. This converts our calculations back to clip space to set the correct gl_Position.

Sanding down the point

There’s one last thing we could improve. As the angle between the two lines decreases, the miter length increases at an increasing rate. Once we hit a pre-defined limit, we should cut off the point, so the corner of the line is flat.

To do this, we need to increase the vertices per point to four. This will allow us to calculate two vertices for the outer joint if the miter length is too large, as shown in the image above.

We need to determine two things in our vertex shader: if the miterLength is above a certain threshold (in this case, 10) and if the vertex we are processing is intended for the outer joint. If either of these is false, we can calculate gl_Position in the same way as before.

We’ll create a new vector, point, which will point in the direction of the outer joint.

vec2 point = normalize(AB - BC);

The sign of the dot product of two vectors tells you whether the angle is acute or obtuse (i.e. whether the two vectors are pointing in the same or opposite directions). If we take the dot product of point and miter, it will be -1 when the outer joint is towards one vertex and +1 when it is towards the other.

Because aCorner.x is -1 for one vertex and +1 for the other, we can determine whether the vertex is on the outer join by multiplying aCorner.x by the dot product of point and miter.

if (miterLength > 10.0 && sign(aCorner.x * dot(miter, point)) > 0.0) {

// trim the corner

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy + (directionToMove * distanceToMove);

} else {

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy + (aCorner.x * miter * uWidth * miterLength) / uScreen.xy;

}

The distance to move is just the width of the line, uWidth.

The direction to move will depend on which vertex we are currently processing. However, branching in our code can hurt our performance, so, ideally, our solution will avoid using statements such as if.

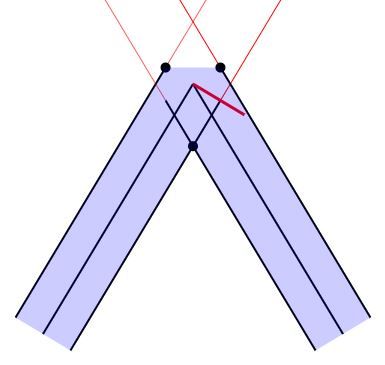

Let’s take another look at the miter tool.

As you can see, the normalA vector gives us a good starting point. The direction of one of our vertices will be the mirror of normalA in the vertical and horizontal axis, and the direction of the other one will be the mirror of normalA in just the horizontal axis.

Multiplying normalA by -1 will give us the direction of the first vertex. We then need a way of leaving the vector in the same direction for one vertex, and mirroring it in the vertical axis for the other vertex. aCorner.y will be -1 for one of these vertices, and +1 for the other. Therefore, if we multiply our vector by aCorner.y, it will give us the desired separation.

(In our diagram, aCorner.y refers to the horizontal axis, as shown below).

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy - (aCorner.y * uWidth * normalA);

This works when the outer joint is in the direction of our diagram, but what happens when it’s facing the other direction?

This time normalA is in the correct direction, so we don’t want to mirror it in the horizontal axis. In other words, our current code works when aCorner.x is +1, but should be mirrored when aCorner.x is -1. We can multiply what we currently have by aCorner.x to produce this result.

Finally, we need to divide our result by uScreen.xy to convert it back to clip space, as before.

if (miterLength > 10.0 && sign(aCorner.x * dot(miter, point)) > 0.0) {

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy - (aCorner.x * aCorner.y * uWidth * normalA) / uScreen.xy;

} else {

gl_Position.xy = gl_Position.xy + (aCorner.x * miter * uWidth * miterLength) / uScreen.xy;

}

Conclusion

Using this approach has plenty of advantages.

By using GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP instead of GL_TRIANGLE, we can reduce the amount of data needed to create a series of triangles (and therefore the amount of information we need to pass over to the buffers).

Ideally, we would do most of these calculations in a geometry shader. It takes the vertices from the vertex shader and transforms them before passing them to the fragment shader. The transformations can include translating the vertices to new coordinates and generating more vertices.

Currently, however, geometry shaders are only available in OpenGL, not WebGL. This is the reason we have to pass four points per vertex into the buffers and manipulate the coordinates in the vertex shader. In this way, we are still able to pass over most of the work to the GPU, allowing us to capture the performance benefits that provides.