Introduction

Developing a greenfield project inherently requires decisions to be made both up front and along the way that have the potential to dramatically steer the course of the journey. This is not just true for the development of the product itself, but also testing methodology and tooling. As a tester, having the right approach for the task at hand is key.

In this blog we will explore decision making around tooling through the lens of my recent experience testing the Python-based API of an open-source project in the air quality and weather forecasting domain. Postman is a ubiquitous name in the API testing world, with a rich UI and ease of use experience. Comparatively, pytest with Requests is a code-level testing framework extended to be able to make API calls. We will examine the reasoning behind our choice to use both tools in different ways to achieve our testing goals.

Background

Our product vAirify will be used by The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). It compares their own air quality forecast to measurements from sensors worldwide, highlighting local divergences. Air quality is affected by contamination from harmful substances (pollutants); we tracked particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and ozone.

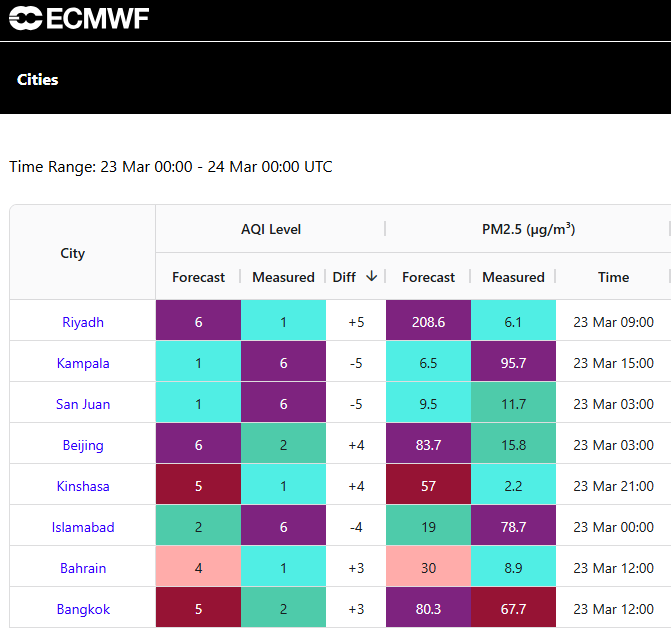

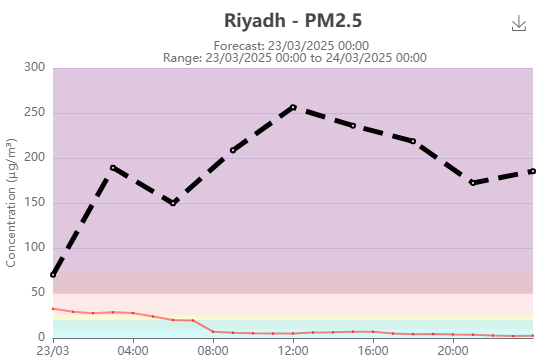

This is all represented in a summary table comparing different cities over a given time period, and graphically in a series of pollutant-level and Air Quality Index (AQI) graphs for specific cities. Read the full story here.

A section of the summary table, showing Riyadh with the highest divergence between forecast and measured AQI data in the specified time range, and data for one of the pollutants

One of the pollutant (PM2.5) graphs for Riyadh showing the forecast reading with a black line, and the measured data from a specific measurement station in a red line

The rest of this article will contain information about testing the backend of the application, however you can read this blog to find out more information on UI-testing the visual outputs.

The API

One of the key elements in the architecture is a Python-based API connecting the UI to the database collections. There is one endpoint for collecting forecast data, and two for local measurements (one retrieving only summary data). When preparing our test strategy, a decision needed to be made regarding how to functionally test these endpoints, with Postman an immediate frontrunner.

Postman

Postman allows you to create collections of multiple requests targeting specific endpoints, which can be run either manually or scheduled. Getting up and running is a painless process and so jumping onto testing something is no trouble beyond installing the desktop application. Setting up requests is very straightforward; parameters, authorisation credentials, headers and request bodies are set in UI tabs.

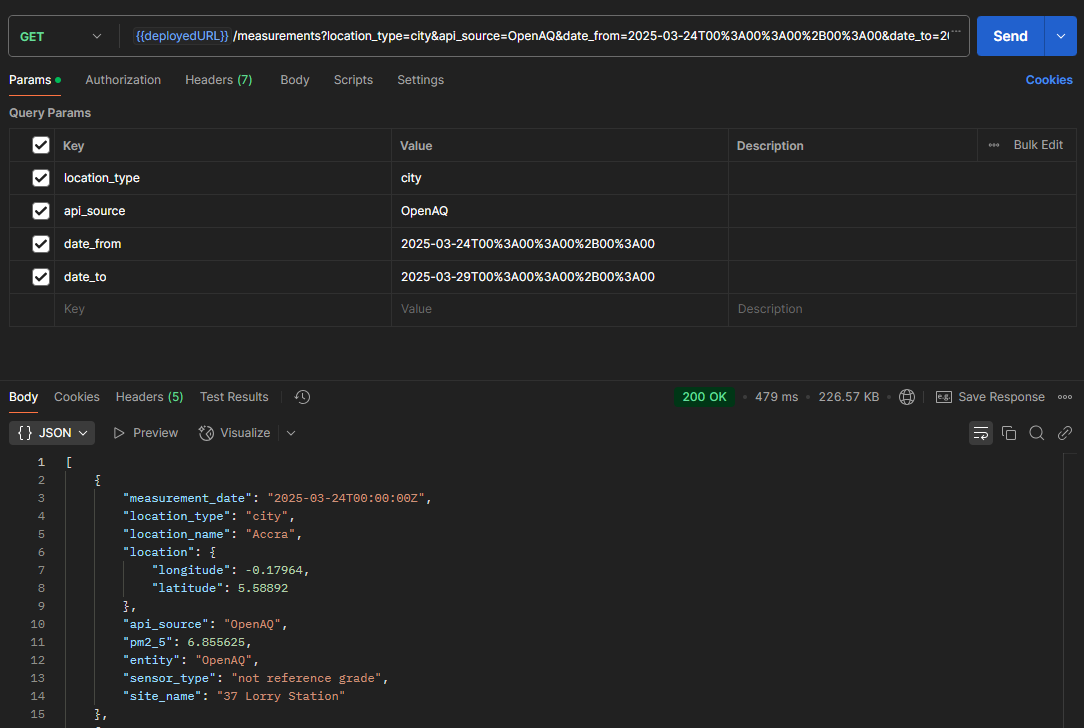

A request to the measurements endpoint using the Postman UI and some resultant data, with the request URL built from the constituent query parameters provided in the table

Simultaneously tests can be written in JavaScript using Chai assertions (or there are pre-prepared code snippets for common examples you can select). These tests execute against the response to the request, and information regarding their passing or failing is provided in the UI. All of these elements result in the experience being straightforward and it can be easy to hit the ground running.

Being able to visualise the request is extremely helpful for debugging issues or failing tests, and for investigating the API to learn more about its capabilities. Tweaking parameters and operating in a more exploratory fashion is an intuitive way of working.

Having said this, the nested nature of the user interface can make maintaining tests in the long term a significant overhead. In my experience, it can be challenging to immediately understand the scope of a test without needing to flip back and forth between tabs and tests, keeping track of the pre-request scripts that affect them. Making changes can require a lot of clicks, particularly if a change is needed across a variety of tests.

Also, there are some limitations with Postman depending on the pricing plan that is being used. This can have impacts on the number of collaborators that can work in a shared workspace and the number of times a collection of tests can be manually run in a month.

pytest with Requests

We identified that it would be useful to have our backend integration tests written in the same language as the application, with a key benefit being to facilitate collaboration between developers and testers. If a problem were to arise, having the test code written in Python removes the need for significant context-switching when working together to diagnose and resolve the issue. Similarly for approving pull requests. It also allows the test code to live within the same repository as the source code which would be a benefit as all of the project and documentation could be simply managed through the same repository.

While researching if there was a Python library similar to REST Assured (the framework for testing Java APIs) that we could use for our API tests, we started looking at pytest with the Requests library. The pytest framework was already in the project, being used by the developers to write their unit tests for the backend Python code. However, its use case is not limited to unit testing. Requests is a library that allows HTTP requests to be made from within a pytest test, thus extending the pytest functionality and facilitating API testing.

An important part of API testing is verifying different parameters work as expected when passed in specific combinations or undertaking boundary value analysis. Both activities can produce a lot of test cases if each test case is quite atomic in its definition and approach. Alternatively with parametrisation you can create tests that are more flexible by passing in different arguments in the test setup. These arguments could be, for example, test data and the expected response from the API given the data provided. pytest is well suited for this kind of data driven testing due to the inbuilt parametrisation decorator.

Let’s see how this works

In the below simple use case is an example parametrised pytest test using the Python module Requests to make a GET request to the forecast endpoint. The request parameters are passed in as a dictionary ‘payload’. The location_name parameter is optional for this endpoint, however base_time, valid_time_from, valid_time_to and location_type are required. The test asserts the response has a status code 200 when all required parameters are present, with or without the optional parameter, indicating the request was a success.

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"payload",

[

{

"base_time": "2025-03-24T00:00:00+00:00",

"valid_time_from": "2025-03-24T00:00:00+00:00",

"valid_time_to": "2025-03-29T00:00:00+00:00",

"location_type": "city",

"location_name": "London",

},

{

"base_time": "2025-03-24T00:00:00+00:00",

"valid_time_from": "2025-03-24T00:00:00+00:00",

"valid_time_to": "2025-03-29T00:00:00+00:00",

"location_type": "city",

},

],

)

def test__required_parameters_provided__verify_response_status_200(payload: dict):

response = requests.request(

"GET", "http://localhost:8000/air-pollutant/forecast",

headers={"accept": "application/json"},

params=payload,

timeout=5.0

)

assert response.status_code == 200

How to proceed

We decided the best approach would be to leverage the benefits of both tools. The automation of the API testing would be written in Python using pytest and Requests, however we would use Postman alongside in a supporting role.

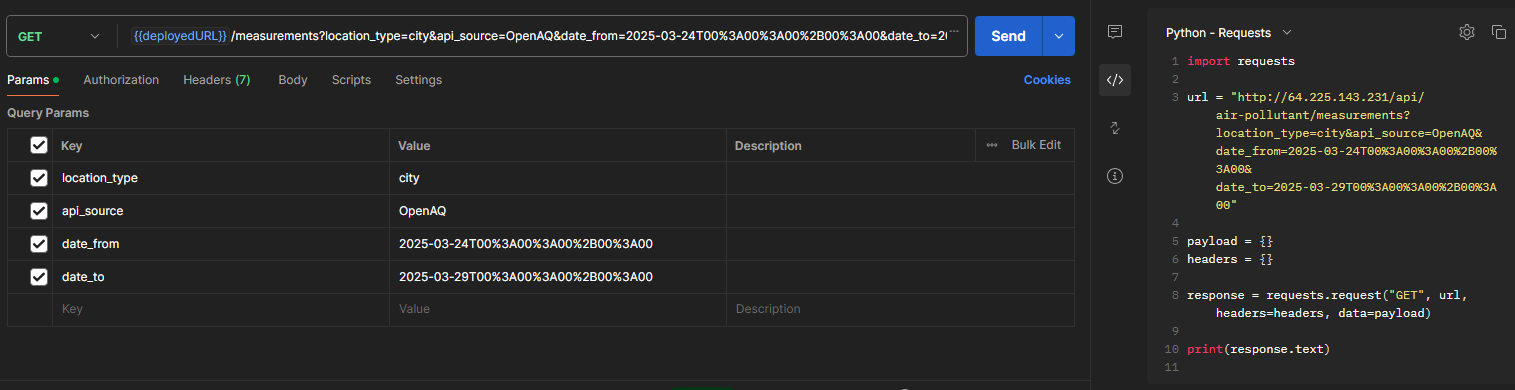

As the endpoints were being developed, it was much easier to launch Postman to get a request working than writing the code necessary to do the same job. The visual nature of the tool allows you to quickly make changes and troubleshoot any obvious problems up front. From this point, we migrated to the Python IDE PyCharm and wrote test files for each endpoint. Helpfully, if needed you can also export Postman requests into different languages to provide a jumping off point into tests at a code level.

As well as doing basic parameter validation (as discussed above), there are tests that seed data to our MongoDB test database collections and assert on the expected data returned by specific API calls.

@pytest.fixture()

def setup_test():

# Test Setup

load_dotenv()

delete_database_data("in_situ_data")

seed_api_test_data(

"in_situ_data",

[

test_city_1_site_1_2024_6_11_14_0_0,

test_city_2_site_1_2024_6_12_14_0_0,

test_city_2_site_2_2024_6_12_15_0_0,

test_city_3_site_1_2024_6_12_13_0_0,

test_city_a_site_1_2024_7_20_13_0_0,

test_city_a_site_2_2024_7_20_14_0_0,

test_city_a_site_3_2024_7_20_15_0_0,

test_city_a_site_4_2024_7_20_16_0_0,

test_city_b_site_1_2024_7_20_13_30_0,

test_city_b_site_2_2024_7_20_16_30_0,

test_city_c_site_1_2024_8_20_16_30_0,

test_city_c_site_2_2024_8_20_17_0_0,

invalid_in_situ_document,

],

)

Seeding the QA database ‘in_situ_data’ with specific data representing readings for test measurement stations at different times

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"test_measurement_base_time_string",

[

measurement_base_time_string_24_7_20_14_0_0,

measurement_base_time_string_24_7_20_15_0_0,

measurement_base_time_string_24_8_20_17_0_0,

],

)

def test__check_measurement_base_time_in_response_is_correct(

setup_test,

test_measurement_base_time_string: str,

):

api_parameters: dict = {

"location_type": location_type,

"measurement_base_time": test_measurement_base_time_string,

"measurement_time_range": measurement_time_range,

}

response: Response = requests.request(

"GET", base_url, params=api_parameters, timeout=5.0

)

response_json: list = response.json()

for city in response_json:

assert city.get("measurement_base_time") == test_measurement_base_time_string

This test is making a request to the measurements summary endpoint, passing in a specific ‘measurement base time’ as a parameter and asserting that each object in the response contains the same date for this key

Our intention was to use a lightweight approach to automated test cases, capturing behaviour that needed to always happen, or should never happen when certain actions are performed. For example, that the correct mean AQI for a pollutant would be calculated and returned by the measurement summary API when provided with various measurement_base_time parameters. These test cases would then be run against every feature ticket that was developed to detect any introduced regression. We would then test other ideas and cover risks using specific test charters (you can read more about these here) and exploratory testing sessions.

In the context of API testing, Postman was the sensible tooling choice to conduct exploratory testing. The UI facilitated trying various parameter permutations, or send potentially bad data to establish the robustness of the design, while maximising our self-imposed timebox of 45–90 minutes. You can find an example of a completed session in our repo wiki here. In the context of our project, trying to do this in code would not have been a time efficient way to test.

Conclusion

Having the automated tests all located within the same codebase made it straightforward for a developer to pick up work on an API test if the testers needed assistance. It was easy to share work and collaborate and get the code reviewed through the same channels that developers were using and kept our workflow as a team easy to understand.

Personally, I find interpreting tests written in code easier to understand and maintain than navigating a nested UI to establish test setup that might span several tabs. This is particularly important if tests fail so that they can be efficiently debugged. But this comes with a trade off in flexibility that makes it much more cumbersome to interrogate a system in an exploratory way. Using Postman is a fantastic way to visualise the endpoint, allowing you to conduct much deep and thorough exploratory testing. I find it easier to be creative with my testing when working this way.

There are a lot of options available when deciding tooling for something as crucial as an API and so the approach described here is not the only way this could have been undertaken successfully. However, the combination of automation with pytest and Requests, and ad hoc / exploratory testing with Postman worked well for us.