The Immutability Gap: Why Java Records Need Optics

Part 1 of the Functional Optics for Modern Java series

Modern Java has done a lot to embrace immutability. Records give us concise, immutable data carriers. Pattern matching lets us elegantly destructure nested structures. Sealed interfaces enable exhaustive type hierarchies. Yet despite these advances, one fundamental operation remains surprisingly painful: updating a value deep within an immutable structure.

This article introduces optics, a family of composable abstractions that complete the immutability story. If pattern matching is how we read nested data, optics are how we write it.

Introducing Higher-Kinded-J

Throughout this series, we use Higher-Kinded-J, a library that unifies two powerful paradigms:

- Optics for navigating and modifying immutable data structures

- Effects for computations that might fail, accumulate errors, or require deferred execution

The first half of this series focuses on Optics: lenses, prisms, and traversals. The second half introduces the Effect Path API, showing how navigation and computation work together. By the end, you will have a complete toolkit for data-oriented programming in Java.

A note on philosophy: Many functional libraries in Java are ports of Haskell or Scala libraries, bringing foreign idioms that feel awkward in Java code. Higher-Kinded-J takes a different approach: Java first. Adopt good ideas from other languages, but this is a Java functional library designed to take advantage of modern Java: records, sealed interfaces, pattern matching, and annotation processing. Higher-Kinded-J is not an imitation; it’s functional programming that feels native to Java.

The Promise of Modern Java

Java’s evolution over the past few years has been remarkable. With records, we can define immutable data types in a single line:

public record Address(String street, String city, String postcode) {}

No more boilerplate. No more mutable fields to worry about. The compiler generates equals(), hashCode(), and toString() for us. Records are final, their fields are final, and they encourage a data-oriented programming style that functional programmers have long advocated.

Pattern matching, introduced progressively from Java 16 onwards, lets us destructure these records elegantly:

if (employee instanceof Employee(var id, var name, Address(var street, _, _))) {

System.out.println(name + " lives on " + street);

}

We can reach into nested structures, extract what we need, and bind values to variables in a single expression. Combined with sealed interfaces, we get exhaustive switch expressions that the compiler can verify:

sealed interface Shape permits Circle, Rectangle, Triangle {}

String describe(Shape shape) {

return switch (shape) {

case Circle(var r) -> "A circle with radius " + r;

case Rectangle(var w, var h) -> "A " + w + " by " + h + " rectangle";

case Triangle(var a, var b, var c) -> "A triangle";

};

}

This is genuinely excellent. Modern Java has become a credible language for data-oriented programming, with immutability at its core.

But there’s a problem.

The Nested Update Problem

Reading nested immutable data is elegant. Writing it is not.

Consider a simple domain model for a company:

public record Address(String street, String city, String postcode) {}

public record Employee(String id, String name, Address address) {}

public record Department(String name, Employee manager, List<Employee> staff) {}

public record Company(String name, Address headquarters, List<Department> departments) {}

Four straightforward records. Nothing complex. Now suppose we need to update the street address of the Engineering department’s manager. In a mutable world, this would be trivial:

company.getDepartment("Engineering").getManager().getAddress().setStreet("100 New Street");

One line. Done. But our records are immutable: there are no setters. Instead, we must reconstruct every record in the path from root to leaf:

public static Company updateManagerStreet(Company company, String deptName, String newStreet) {

List<Department> updatedDepts = new ArrayList<>();

for (Department dept : company.departments()) {

if (dept.name().equals(deptName)) {

Employee manager = dept.manager();

Address oldAddress = manager.address();

// Rebuild address with new street

Address newAddress = new Address(

newStreet,

oldAddress.city(),

oldAddress.postcode()

);

// Rebuild employee with new address

Employee newManager = new Employee(

manager.id(),

manager.name(),

newAddress

);

// Rebuild department with new manager

Department newDept = new Department(

dept.name(),

newManager,

dept.staff()

);

updatedDepts.add(newDept);

} else {

updatedDepts.add(dept);

}

}

return new Company(

company.name(),

company.headquarters(),

List.copyOf(updatedDepts)

);

}

Twenty-five lines of code to change a single string. Every record in the path must be manually reconstructed, copying all unchanged fields. This is the copy constructor cascade, an anti-pattern that plagues immutable codebases.

Don’t despair. By the end of this article, you will see this same operation reduced to a single line. First, let’s understand why simpler approaches fall short.

You might think: “Just add withX() methods to each record.” Indeed, you could:

public record Address(String street, String city, String postcode) {

public Address withStreet(String street) {

return new Address(street, this.city, this.postcode);

}

}

This helps somewhat, but it doesn’t compose. You still need to thread the updated value back through every layer:

var newAddress = manager.address().withStreet("100 New Street");

var newManager = manager.withAddress(newAddress);

var newDept = dept.withManager(newManager);

// ... and so on

The ceremony remains. The boilerplate persists. And the potential for error (accidentally copying the wrong field, forgetting to update an intermediate layer) grows with each level of nesting.

Pattern Matching: Half the Solution

Here’s the insight that motivated this article: pattern matching solves reading nested data, but provides no help for writing.

Consider the asymmetry. To read an employee’s street, we can write:

if (employee instanceof Employee(_, _, Address(var street, _, _))) {

return street;

}

Pattern matching lets us drill down through layers, ignoring fields we don’t care about, and extract exactly what we need. It’s declarative, composable, and elegant.

But to write a new street? We’re back to the imperative copy-constructor cascade. There’s no “pattern setting” in Java. We cannot write:

employee with { address.street = "100 New Street" } // Nested updates: not supported

A Note on JEP 468: Derived Record Creation

Java is making progress here. JEP 468 introduces derived record creation, a with expression for records. Currently in preview (JDK 25), it allows:

Address updated = oldAddress with { street = "100 New Street"; };

This is a very useful start. Instead of manually copying every field, you specify only what changes. The compiler handles the rest.

However, JEP 468 solves single-level updates, not nested ones. You cannot write:

employee with { address.street = "100 New Street" } // Not supported by JEP 468

To update a nested field, you must chain with expressions at each level:

Employee updated = employee with {

address = address with { street = "100 New Street"; };

};

Better than the full copy-constructor cascade, certainly. But you still manually thread updates through each layer. The ceremony shrinks but doesn’t disappear. As nesting deepens (a company containing departments containing employees containing addresses), even chained with expressions become unwieldy.

JEP 468 is a welcome addition, but it addresses syntax, not composability. Optics provide something fundamentally different: reusable, composable access paths that can be defined once and applied anywhere.

The Wider Landscape

Other languages have recognised this gap. Haskell has lenses. Scala has Monocle. F# has property access expressions. C# has with expressions for records (similar to JEP 468). What distinguishes optics is composition: the ability to combine small, focused accessors into larger ones that handle arbitrary depth automatically.

This asymmetry isn’t just inconvenient; it actively discourages immutability. Developers facing the copy-constructor cascade often reach for mutability instead. “Just make the fields non-final,” they say. “It’s simpler.” And in the short term, it is. But mutability brings its own problems: thread safety issues, defensive copying, spooky action at a distance when an object you thought you owned gets modified by code you didn’t control.

The promise of modern Java (clean, immutable, data-oriented code) remains half-fulfilled. Pattern matching gave us elegant reading. Now we need elegant writing.

Pattern matching is half the puzzle; optics complete it.

Optics: A New Mental Model

An optic is a first-class representation of an access path into a data structure. Think of it as a reified getter-and-setter pair that can be composed, stored, and passed around.

The key insight is that access paths compose. If you have a way to focus on an employee’s address, and a way to focus on an address’s street, you can combine them to focus on an employee’s street. This composition is the heart of optics.

Consider an analogy: XPath for objects. In XPath, you might write /company/departments/manager/address/street to navigate to a specific element. Optics provide similar navigation, but:

- They’re type-safe: the compiler ensures your path is valid

- They support both reading and writing

- They compose with standard function composition

The simplest optic is a lens. A lens focuses on exactly one value within a larger structure. Given a lens from Employee to Address, you can:

- Get the address from any employee

- Set a new address, returning a new employee with everything else unchanged

- Modify the address using a function, returning a new employee

Here’s what a lens looks like conceptually:

public record Lens<S, A>(

Function<S, A> get,

BiFunction<A, S, S> set

) {

public S modify(Function<A, A> f, S whole) {

return set.apply(f.apply(get.apply(whole)), whole);

}

}

Two functions: one to extract, one to replace. The modify method combines them: extract the value, transform it, put it back.

The magic happens when you compose lenses:

public <B> Lens<S, B> andThen(Lens<A, B> other) {

return Lens.of(

s -> other.get(this.get(s)),

(b, s) -> this.set(other.set(b, this.get(s)), s)

);

}

Given a lens from Employee to Address and a lens from Address to String (the street), andThen produces a lens from Employee to String. The composed lens automatically handles the intermediate reconstruction, eliminating the manual copy-constructor cascade.

Optics have a rich history. They emerged from the Haskell community in the early 2010s, with Edward Kmett’s lens library becoming the definitive implementation. The ideas spread to Scala (Monocle), PureScript, and other functional languages. The theoretical foundations connect to category theory, though you needn’t understand the theory to use optics effectively.

For Java developers, the practical takeaway is this: optics let you treat deeply nested immutable updates as simple, composable operations. The same twenty-five-line method becomes a single expression.

The Optics Family

Lenses are just one member of a family of optics. Each type handles a different kind of focus, a concept worth unpacking.

When we say an optic “focuses” on a value, we mean it provides a way to zoom in on that value within a larger structure. The focus might be:

- Guaranteed (always exactly one target)

- Conditional (zero or one target, depending on the data)

- Multiple (zero to many targets)

Different optic types encode these different guarantees. Understanding which optic to use comes down to asking: “How many values might this path target, and is the targeting guaranteed to succeed?”

Lens: Focus on Exactly One (Has-A)

A lens focuses on exactly one value that is guaranteed to exist. It’s the optic for “has-a” relationships:

- An

Employeehas anAddress - An

Addresshas astreet - A

Departmenthas amanager

Lenses always succeed: you can always get the focused value, and you can always set a new one.

Prism: Focus on One Variant (Is-A)

A prism focuses on one variant of a sum type. It’s the optic for “is-a” relationships:

sealed interface Shape permits Circle, Rectangle {}

record Circle(double radius) implements Shape {}

record Rectangle(double width, double height) implements Shape {}

A prism for Circle provides two operations:

- Match: Extract the

Circlefrom aShape, if it is one (returningOptional) - Build: Construct a

Shapefrom aCircle(always succeeds)

The key insight is that prisms are partial isomorphisms. They can always go one direction (build), but might fail in the other (match). Not every Shape is a Circle, so matching might fail. But every Circle is a Shape, so building always works.

This asymmetry is what distinguishes prisms. They’re perfect for sealed interfaces and enums, where you want to focus on a specific variant.

Traversal: Focus on Many (Has-Many)

A traversal focuses on zero or more values simultaneously. It’s the optic for collections:

- A

Departmenthas manyEmployees in its staff list - A

Companyhas manyDepartments

Traversals let you modify all focused values at once:

// Give every employee in the department a raise

Traversal<Department, BigDecimal> allSalaries = ...;

Department updated = allSalaries.modify(s -> s.multiply(RAISE_FACTOR), dept);

Every employee’s salary is updated. The traversal handled the iteration internally.

The Optics Hierarchy

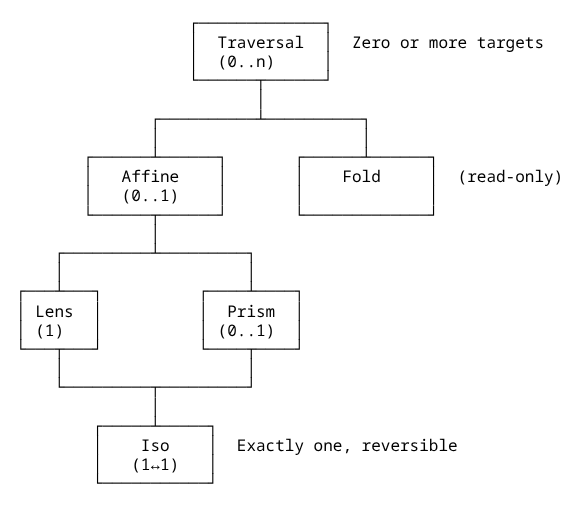

Optics form a hierarchy based on their focusing power. The diagram below shows how they relate. Read it from bottom to top: more specific optics (at the bottom) can always be used where more general ones (at the top) are expected.

Reading the diagram:

-

Iso (bottom): The most specific optic. It focuses on exactly one value and can convert in both directions without loss. Think of it as a reversible transformation, like converting between Celsius and Fahrenheit, or between a record and its tuple representation.

-

Lens and Prism (next level up): Both focus on at most one value, but in different ways. A Lens always succeeds (the field exists); a Prism might fail (the variant might not match). They converge at Iso because an Iso can do both: it always succeeds and always has a reverse.

-

Affine (middle): Combines the “might not exist” aspect of Prism with the “no construction” aspect of Lens. An Affine focuses on zero or one value without guaranteeing either. Use it for optional fields, map lookups, or any path that might not resolve.

-

Fold (read-only branch): Like a Traversal but only for reading. Useful when you need to extract or aggregate values without modifying them.

-

Traversal (top): The most general. It can focus on any number of values (zero, one, or many). Every other optic can be used as a Traversal.

How Composition Works

When you compose two optics, the result is the “least powerful” optic that can represent both:

- Lens + Lens = Lens: Both always focus on exactly one value

- Lens + Prism = Affine: The prism might not match, so the result might focus on zero or one

- Anything + Traversal = Traversal: Once you have multiple potential targets, you stay there

The intuition: composing optics that might fail to focus yields an optic that reflects that uncertainty. A lens through a prism becomes an Affine because the prism might not match.

Affine vs Prism: The Subtle Difference

Both Affine and Prism focus on zero or one value, so what’s the difference?

Prism: Can construct the whole from the part. A Circle prism can build a Shape from a Circle. Prisms are for sum types where the part is a valid whole.

Affine: Cannot construct, only access. Looking up a key in a map might fail, but you cannot “build” a map from a single value. Affines are for optional access without construction.

The practical distinction:

- Use Prism for sealed interface variants, enum cases, or any “is-a” relationship where you might want to construct the parent type

- Use Affine for optional fields, map lookups, list indexing, or paths through a prism followed by a lens

When you compose a Lens with a Prism, the result is an Affine. You’ve lost the Prism’s ability to construct (the Lens doesn’t know how) but kept the “might not exist” semantics.

Higher-Kinded-J provides full Affine support, completing the optics hierarchy.

When to Use Each

| Optic | Targets | Can Construct? | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iso | Exactly 1, reversible | Yes (both ways) | Lossless conversions, newtype wrappers |

| Lens | Exactly 1 | No | Record fields, guaranteed “has-a” |

| Prism | 0 or 1 | Yes (one way) | Sealed interface variants, enum cases |

| Affine | 0 or 1 | No | Optional fields, map lookups |

| Traversal | 0 to many | No | Collections, bulk operations |

In practice, you’ll compose these freely. Navigating to “the salary of every full-time employee in a company” requires a traversal (for the department list), another traversal (for the employee list), a prism (for full-time employees), and a lens (for the salary). Accessing an optional configuration value uses an Affine. Converting between a record and its field tuple uses an Iso.

The Payoff: Optics in 60 Seconds

Before diving deeper into theory, let’s see the payoff. Here’s the twenty-five-line method from earlier:

// Manual approach: ~25 lines

public static Company updateManagerStreet(Company company, String deptName, String newStreet) {

List<Department> updatedDepts = new ArrayList<>();

for (Department dept : company.departments()) {

if (dept.name().equals(deptName)) {

Employee manager = dept.manager();

Address oldAddress = manager.address();

Address newAddress = new Address(newStreet, oldAddress.city(), oldAddress.postcode());

Employee newManager = new Employee(manager.id(), manager.name(), newAddress);

Department newDept = new Department(dept.name(), newManager, dept.staff());

updatedDepts.add(newDept);

} else {

updatedDepts.add(dept);

}

}

return new Company(company.name(), company.headquarters(), List.copyOf(updatedDepts));

}

And here’s the same operation with optics:

// Optics approach: 1 line

private static final Lens<Employee, String> employeeStreet =

Employee.Lenses.address().andThen(Address.Lenses.street());

private static final Lens<Department, String> managerStreet =

Department.Lenses.manager().andThen(employeeStreet);

public static Department updateManagerStreet(Department dept, String newStreet) {

return managerStreet.set(newStreet, dept);

}

Define the path once. Use it anywhere. The lens composition handles all the intermediate reconstruction automatically.

Want to give all employees in a department a 10% raise? With manual code, you’d need nested loops and careful reconstruction. With optics:

// Define the path to all salaries once

private static final Traversal<Department, BigDecimal> allSalaries =

Department.Lenses.staff().andThen(Traversals.list())

.andThen(Employee.Lenses.salary());

public static Department giveEveryoneARaise(Department dept) {

return allSalaries.modify(salary -> salary.multiply(new BigDecimal("1.10")), dept);

}

A single expression. No loops. No manual reconstruction. The traversal handles the collection, the lenses handle the path. Every employee gets their raise, and every intermediate record is reconstructed correctly.

If this intrigues you, read on.

First Taste: A Simple Lens

Let’s build a working lens from scratch. We’ll start with the core abstraction:

public record Lens<S, A>(

Function<S, A> get,

BiFunction<A, S, S> set

) {

public static <S, A> Lens<S, A> of(Function<S, A> getter, BiFunction<A, S, S> setter) {

return new Lens<>(getter, setter);

}

public A get(S whole) {

return get.apply(whole);

}

public S set(A newValue, S whole) {

return set.apply(newValue, whole);

}

public S modify(Function<A, A> f, S whole) {

return set(f.apply(get(whole)), whole);

}

public <B> Lens<S, B> andThen(Lens<A, B> other) {

return Lens.of(

s -> other.get(this.get(s)),

(b, s) -> this.set(other.set(b, this.get(s)), s)

);

}

}

Now we can define lenses for our records:

public record Address(String street, String city, String postcode) {

public static final class Lenses {

public static Lens<Address, String> street() {

return Lens.of(

Address::street,

(newStreet, addr) -> new Address(newStreet, addr.city(), addr.postcode())

);

}

}

}

The pattern is mechanical: the getter is the record accessor, the setter creates a new record with one field changed. In production code with Higher-Kinded-J, the @GenerateLenses annotation generates these automatically.

Composition is where the magic happens:

Lens<Employee, String> employeeStreet =

Employee.Lenses.address().andThen(Address.Lenses.street());

// Get the street

String street = employeeStreet.get(employee);

// Set a new street (returns a new Employee)

Employee updated = employeeStreet.set("100 New Street", employee);

// Modify the street (returns a new Employee)

Employee uppercased = employeeStreet.modify(String::toUpperCase, employee);

One composed lens replaces what would otherwise be multiple levels of manual reconstruction. Deep updates now become shallow expressions.

What’s Coming

This article introduced the problem (the immutability gap) and sketched the solution (optics). We’ve seen:

- Why nested immutable updates are painful in Java

- How pattern matching solves reading but not writing

- The optics family: iso, lens, prism, affine, traversal

- A quick win showing the dramatic code reduction

What Higher-Kinded-J Provides

As introduced at the start, Higher-Kinded-J unifies optics and effects. For optics, it provides:

- Production-ready optics: Lens, Prism, Affine, Traversal, Iso, and more, with proper composition and laws

- Annotation-driven generation:

@GenerateLenses,@GeneratePrisms, and@GenerateFocuseliminate boilerplate - The Focus DSL: A fluent API for navigation without explicit composition

- Zero runtime overhead: All the abstraction happens at compile time

For effects (covered from Part 5 onwards):

- Effect Path API: MaybePath, EitherPath, ValidationPath, TryPath, IOPath

- Railway-style error handling: Explicit success/failure tracks with composition

- Bridge methods: Seamlessly connect Focus paths to Effect paths

The library fills a gap in the Java ecosystem. While Scala has Monocle and Haskell has the lens library, Java has lacked a mature, idiomatic implementation. Higher-Kinded-J brings these patterns to Java without sacrificing type safety.

You don’t need to understand higher-kinded types to use the library effectively. The APIs are intuitive: compose lenses with andThen, navigate with Focus paths, handle errors with Effect paths. The underlying type machinery stays out of your way.

The Road Ahead

Next time, in Part 2 we’ll dive deeper into optics fundamentals:

- Lens laws and why they matter for correctness

- Prisms for sum types and sealed interfaces

- Affines for optional values

- Traversals for collections and bulk operations

- Setting up Higher-Kinded-J for annotation-driven lens generation

From Part 3 onwards, we’ll build an expression language interpreter, the canonical optics showcase, demonstrating how these abstractions shine for AST manipulation, tree transformations, and effectful operations.

By the end of this series, you’ll not want to update nested data manually again.

Article Code

You can see the full runnable Java code from the examples

Further Reading

Data-Oriented Programming in Java

-

Brian Goetz, “Data-Oriented Programming in Java” (InfoQ, 2022): Goetz’s foundational article explaining the philosophy behind Java’s DOP features.

-

Scott Logic, “Algebraic Data Types and Pattern Matching with Java”: An excellent introduction to ADTs in modern Java, explaining product types, sum types, and how sealed interfaces with pattern matching supersede the Visitor pattern.

-

JEP 395: Records, JEP 409: Sealed Classes, JEP 441: Pattern Matching for switch: The JDK Enhancement Proposals that brought DOP to Java, essential for understanding the design rationale.

-

JEP 468: Derived Record Creation (Preview): The

withexpression for records (preview in JDK 25), addressing single-level updates (though not nested ones). -

Chris Kiehl, Data-Oriented Programming in Java (Manning): A practical guide to DOP in modern Java, covering records, sealed types, and functional patterns.

The Broader DOP Philosophy

-

Eric Normand, Grokking Simplicity (Manning, 2021): An accessible introduction to functional thinking and data-oriented design from the Clojure perspective.

-

Rich Hickey, “The Value of Values” (Strange Loop, 2012): The influential talk that shaped modern thinking about immutable data, from Clojure’s creator.

Higher-Kinded-J

-

Higher-Kinded-J: Source code, documentation, and examples.

-

Optics Introduction: API reference for lenses, prisms, and traversals.

-

Focus DSL Guide: Fluent navigation with FocusPath, AffinePath, and TraversalPath.

-

Effect Path API Guide: Railway-style error handling with MaybePath, EitherPath, and ValidationPath.

Next time

Next time, in Part 2 we dig into the three main optics: lenses, prisms, and traversals.